Nelson Mandela

(1918–2013)

Anti-apartheid activist and first democratically elected president of South Africa

President Nelson Mandela dedicated his life to securing the freedom of the people of South Africa by confronting the apartheid regime, which violently oppressed Black South Africans. Starting in 1652, Dutch and British colonists slowly annexed trade ports and other strategic areas of what is now South Africa. Finally, in 1910, the Union of South Africa was established, with only whites allowed political power, dictated by apartheid.

President Mandela rose up against apartheid, joining the African National Congress in 1944. In 1963, the government arrested him and sentenced him to life in prison the following year.

The human rights champion continued his struggle from prison. He secretly studied with others who were incarcerated. These secret lectures came to be known as “Mandela University.” In February 1990, the government finally released Mandela and he immediately led discussions with the South African government to dismantle the apartheid system. In 1994, the first democratic elections were conducted with nonwhite candidates, and Mandela was elected the first Black president of South Africa. Around this time, Mandela declared:

A man who takes away another man’s freedom is a prisoner of hatred; he is locked behind the bars of prejudice and narrow-mindedness. … The oppressed and the oppressor alike are robbed of their humanity.”[1]

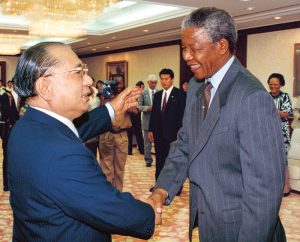

Ikeda Sensei first met Nelson Mandela in October 1990. As Mandela had become acquainted with the Buddhist leader’s writings during his time in prison. The two men agreed to hold an exhibit to inform the Japanese people of the injustices of apartheid. They met again in July 1995 at the Tokyo State Guesthouse, where Sensei conferred on President Mandela an honorary doctorate from Soka University. They also discussed the importance of fostering capable successors. Sensei has said of President Mandela:

Mr. Mandela remained undefeated. The more difficult his situation, the more optimistic he became. That was because he believed in turning suffering into hope.[2]

Linus Pauling

(1901–94)

Leading 20th century scientist and peace activist

Dr. Linus Pauling, known as the father of modern chemistry, developed the foundation for quantum mechanics and molecular biology. In 1954, he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Dr. Pauling was inspired by his wife, Ava Helen, to promote peace and the abolition of nuclear weapons. He worked with Albert Einstein and other scientists to inform the world of the horrific nature of nuclear weapons. They developed the Russell-Einstein Manifesto, which outlined the dire consequences of nuclear war. In addition, he led a petition signed by 13,000 scientists calling for an end to producing nuclear weapons.

The U.S. government viewed Dr. Pauling with suspicion. They labeled him a communist in the 1950s, simply because he disagreed with America’s policy of nuclear arms development. As a result, he was forced to resign as chairman of chemistry and chemical engineering at Caltech. But in 1964, Linus Pauling was recognized for his invaluable efforts and received the Nobel Peace Prize, making him the first person to receive two unshared Nobel Prizes.

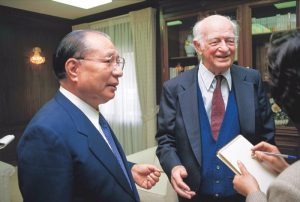

Ikeda Sensei first met him in February 1987. Their dialogues were compiled into a book titled A Lifelong Quest for Peace. In his preface, Dr. Pauling wrote:

The destruction caused by World War I and World War II was so great that neither the winners nor the losers benefited. All nations suffered severely in terms both of lives lost and material wealth destroyed. A third world war would be different: it would wreak irreparable damage not only on the warring nations, but on everyone else on Earth as well.

The time has come to recognize these facts and to take the actions they indicate. We must save the money now being wasted on militarism and use it to benefit human beings everywhere.

For decades, both Daisaku Ikeda and I have been working to achieve the goals of disarmament, world understanding and universal peace.[3]

Sensei and Dr. Pauling affirmed their commitment to develop a world where war no longer exists. Today, the building with the chemistry and physics laboratories at Soka University of America is named Linus and Ava Pauling Hall.

Rene Huyghe

(1906–97)

Art historian who fought to restore the human spirit and saved countless works of art during World War II

Rene Huyghe is best known for saving the art collection of the world-famous Louvre Museum in Paris during the Nazi occupation. In 1937, Huyghe became chief curator of paintings at the Louvre. He made his mark by transforming the display of paintings from a stacked style, with paintings on top of others, to one main line at eye level, hanging them in a way that tells a story. In this way, Rene Huyghe cherished each work of art.

When the Nazis occupied France in 1940, they sent a group to ransack the priceless treasures of the Louvre. Huyghe, however, had anticipated this possibility and had begun to send artworks away for storage in the South of France. When the Nazis arrived, Huyghe negotiated with them, proposing outrageous conditions, which delayed an agreement and bought the time necessary to evacuate the artwork.

Rene Huyghe first met Ikeda Sensei on a trip to Japan in April 1974, when the Mona Lisa was on display in Japan for the first time. Since then, Huyghe and Sensei met on more than 10 occasions before he passed away in 1997.

Their dialogues culminated in a book titled Dawn After Dark. Their shared goal was the restoration of the human spirit through art and culture. Sensei observes in their dialogue:

Freedom depends on deepening the inner life. Given a piano, a person can sell it. He can smash it with a hammer. He can produce hideous noise by banging on the keyboard. But these courses of action produce no true value. To make good use of the instrument, he must control himself enough to master the techniques of performing on it. Generating maximum value demands acquiring maximum skill. Self-mastery to make this possible is supreme freedom. Attaining such liberty is a manifestation of true human dignity.[4]

Huyghe remarked that human revolution was what he was earnestly seeking and was committed to work for the “dawn of human revolution.”[5]

Now, at the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum, stands the “Huyghe Cherry Tree.”

Wangari Maathai

(1940–2011)

Environmentalist and founder of the Green Belt Movement

Wangari Maathai founded the Green Belt Movement that initiated the planting of more than 30 million trees in Kenya to stop environmental destruction. She was the first African woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004.

In addition to protecting the environment, Wangari Maathai also dedicated herself to women’s empowerment and fighting poverty. Women were the ones who organized the Green Belt Movement. Maathai inspired in them the belief that they could make the greatest contribution to the world and their children’s future through treeplanting. In her Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, she said:

Today we are faced with a challenge that calls for a shift in our thinking, so that humanity stops threatening its life-support system. We are called to assist the Earth to heal her wounds and, in the process, heal our own—indeed, to embrace the whole creation in all its diversity, beauty and wonder. This will happen if we see the need to revive our sense of belonging to a larger family of life, with which we have shared our evolutionary process.[6]

In February 2005, Ikeda Sensei met with Wangari Maathai, and wrote the following in an essay on this hero of environmental protection:

Planting a tree is planting life; it is fostering the future, fostering peace—these are beliefs that Dr. Maathai and I found we shared at the deepest level when we met and talked.[7]

Maathai’s legacy is honored today at Soka University of America with the Environmental Sciences building named Wangari Maathai Hall.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles