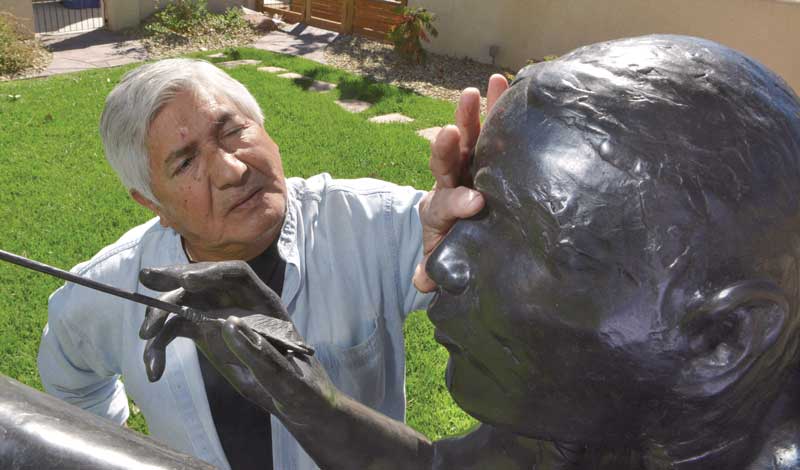

Acclaimed Native American sculptor Michael Naranjo’s work appears on this week’s World Tribune cover. During the Vietnam War, a grenade took Naranjo’s eyesight and permanently maimed his right hand.

Amid his recovery in Japan, Naranjo began sculpting with clay, and with relentless practice, turned his passion into a career. To be sure, his work became so critically acclaimed that the Italian government permitted him to mount a special scaffolding around Michelangelo’s David in Florence so that he could visit the masterpiece by touch. His works today are part of the White House, Heard Museum and Vatican art collections, among others.

World Tribune: Thank you for taking the time to meet with us. You are a celebrated Native American sculptor who happens to be blind. Where and how did you learn your spirit of resilience?

Michael Naranjo: Everyone’s life is connected to their past. I have a brother, Tito, who is seven years older than me. Growing up, he was like my mother and my father. We spent many days up in the mountains and nature. There, it’s a different world. He wanted to see what was over the next ridge, and you had to struggle to get there. He was there for me, always. I think that had a lot to do with it.

I also think it makes a great deal of difference who stands beside you. Laurie (my wife)—we’re connected at the hip. One morning, I woke up and said, “I feel grumpy this morning,” as I got out of bed. She said, “OK. I have the solution.” She put me back in bed and rolled me over and over and then told me to get up. She said, “You just got up on the wrong side of the bed.” It’s who you’re surrounded by. In my situation, she’s always there.

WT: What a beautiful relationship. How did you decide to be a sculptor?

Naranjo: I always wanted to be a sculptor, even when I was young. When I was in the hospital with one good hand and no eyes—that was the beginning. I thought that if I couldn’t do it, then I’d never be able to do it.

I made some very small crude figures at first. And when I returned home, I spent hours, days and nights reading (audio) books and working long into the night. I would sleep for two or three hours and with such determination go back [to sculpting].

WT: We understand that your daughter, Jenna Naranjo Winters, an award-winning journalist, did a documentary about your life, titled Dream Touch Believe.

Naranjo: Yes, in the documentary, I talk about one particular piece. In the middle of the night, I woke sitting up. I had been dreaming about the sculpture I was creating. It must have been 20-feet tall.

One day, I went out [to my studio] at 10 p.m. Next thing I knew, the birds were singing. A few days later, I dreamed I was working on the scaffolding, and I was looking through my statue’s eyes and looking at myself.

To be there to that degree—how do you get there? I don’t know. I guess it’s being one with what you’re doing. That’s it—to be one with something.

WT: Being one with your environment resonates with Buddhist thought. Was there a specific moment when you realized that blindness would not limit your creativity?

Naranjo: I wanted to live. I wanted to do things. The only way you can do that is to try. If you don’t try, as Laurie and I say, you can’t succeed. It doesn’t have to be a race. Once you take that first step, it’s a beginning.

WT: Speaking of first steps, many artists struggle with beginning a new project. How do you feel when you start a new piece?

Naranjo: I always get afraid of starting. I procrastinate and put it off. Once I put my hands on the material and the concept is in my mind’s eye, then I’m lost.

We’re one with our environment if we choose to be, if we want to be, if we work at it. We can do it. It’s ours.

WT: Your sculptures are based on touch. What do you think touch allows us to understand that vision alone often misses?

Naranjo: It’s a different world of sound and touch, which is my world. You don’t see all that’s out there until someone tells you what’s not pleasant. A lot of what I see is good. If we can see more good than bad, perhaps we can get a little bit farther.

WT: If you could speak directly to young artists facing sudden change or loss, what would you want them to know about creating meaning when the future looks uncertain?

Naranjo: Know what you want to do. Know where you’re going and give it your all. Your attitude is going to get you there. Listen to that positive thing that we have inside of us that says, “If we only try, maybe we can get it done.” It’s OK to fail. I’ve failed many times. Who doesn’t? But once again, if you don’t try, you can’t succeed.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles