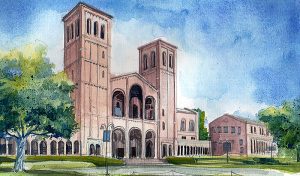

It is a great pleasure to have this opportunity to speak at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), an institution that carries on the finest traditions of higher learning. For this privilege, I thank President Charles E. Young, Vice President Norman Miller, the faculty, and students, men and women who will guide your country into the next century.

The Path of Moderation

Arnold J. Toynbee, historian and philosopher, remains deeply concerned about the fate of humanity in the coming century. At his invitation two years ago (1972) and last May (1973), for approximately ten days, I had the opportunity to engage in dialogue with this great thinker. Our discussions have been a source of personal enrichment and intense intellectual stimulation for me.1

Toynbee sets a demanding example of industry for the members of the younger generation. At the age of eighty-five he rises at 6:45 every morning, and by nine o’clock he is at the desk in his study, ready for work. I once saw him seated at that desk and was struck by the beauty of his old age. Toynbee related to me an episode about the industrious third-century Roman emperor Lucius Septimius Severus (146–211), who, on the day of his death, though seriously ill and still commanding his troops in the cold of northern England, gave his men the word laboramus, or “let us work,” as their motto. The British historian adopted this motto as his own, he told me. That, I thought, was the secret of his enduring vigor and his determination to continue his tasks. Toynbee has the kind of beauty that stems from his lifelong intellectual struggle and soul-searching.

Our talks ranged over an immense field of topics, including civilization, life, learning, education, literature, art, science, international affairs, modern society, human nature, and women. Toynbee was urgently concerned with the course of events after his own death. He very much wanted to leave behind an inspiring message for those who will follow. His desire to assist future generations was the dominant theme of our discussions. I hope that, at its close, my life will reveal no less intense a dedication to the well-being of posterity.

According to Toynbee, the twentieth century’s intoxication with technology has led to the poisoning of our environment and has created the possibility that humanity may destroy itself. He believes that any solution to the current crisis depends on self-control. Mastery of the self, however, cannot be achieved through either extreme self-indulgence or extreme asceticism. The people of the twenty-first century must learn to walk the middle path, the way of moderation.

I find this injunction to be especially congenial, because the ideals of moderation and the middle way are pervasive elements in Mahayana Buddhism. Moderation, in this sense, refers to a way of life that is a synthesis of materialism and spirituality. The path of moderation is the only answer to the current crisis of civilization.

To follow that path, however, humankind requires a reliable guide. Toynbee and I pondered some methodological problems as well, but we agreed that preoccupation with techniques will get us nowhere. In searching for the kind of guide needed today, we must return to such basic issues as the nature of humanity and the meaning of existence, both of which necessarily lead to the question of the essential quality of life. Knowing what we really are, what life is, is fundamental to the understanding of cultures and civilizations. I believe that when the people of the twenty-first century are able to perceive the true nature of life, humanity will move away from infatuation with technology and create a civilization that is humane in the richest, fullest meaning of the word.

One of the primary teachings of Buddhism is that human life is a composite of sorrows; the burden of birth, the agony of growing old, the pain of illness, the grief of the death of loved ones, and ultimately one’s own death. These are the most basic sufferings, but there are others. Pleasant times are fleeting; we must all face the sadness of seeing them end. In today’s society there are many causes for unhappiness; the presence of racial and ethnic discrimination, for example, and the widening gap between rich and poor.

In our lives, grief and pain occur for many different reasons, but what is the cause for sorrow itself? The Buddhist answer is that nothing in the universe is constant, and that sorrow is the result of the human inability to understand that basic principle. The transient nature of all phenomena is self-evident. The young must grow old, the healthy become ill, all living creatures must eventually die, and all that has form ultimately decays. As Heraclitus said almost two and a half millennia ago, all things are in a constant state of flux; nothing in the universe remains the same, but everything shifts from instant to instant like the current of a mighty river. In spite of what our senses may suggest, nothing is immutable. Moreover, it is a basic tenet of Buddhism that clinging fast to the illusion of permanence causes the sufferings of the human spirit.

Attachment to the Transient

To hope for permanence is only human. We all want beauty and youth to last forever. As we work to acquire the good things of the world, we trust that whatever wealth we may accumulate will endure. Still we realize that, no matter how hard we work and no matter how large our bank accounts grow, we cannot, as the saying goes, take it with us. Recognizing this, we continue to work in order to enjoy the benefits of our earnings, and naturally we want to enjoy them for as long as we can. This is one source of sorrow; we cannot keep the fruits of our labor forever. The same is true of our human relationships. No matter how great the love one feels or how much one wants it to endure, a day of parting must come. The loss of a loved one—husband, wife, parent, child, friend—causes the greatest spiritual suffering that we are called upon to face.

Attachment to people leads to grief; attachment to things and the greedy desire for material goods can be the source of conflict; attachment to power often leads to war. Too much attachment to one’s own life can cause a descent into a morass of worry and fear. Most of us actually do not worry constantly about the imminence of death. On the contrary, we carry out the affairs of our daily lives more or less convinced that we will live on for the indefinite future. There are people, however, who are unable to assume this blindly optimistic attitude. Possessed by a frantic desire to stay alive as long as they can, they are consumed by the fear of death, aging, and illness.

No matter what we do, human life keeps changing. Our own bodies, which represent a physical manifestation of the incessant transformation of the universe, must someday die. To live our lives sanely and with meaning, we must face our fate coolly and without fear. In Buddhist terms, the path to enlightenment cannot be traveled without the acceptance of constant, universal change.

But it would be wrong to dismiss entirely the usefulness of attachments to things, even though they are impermanent. As long as we are alive and human, it is perfectly natural that we strive to preserve life, value the love of others, and enjoy the material benefits of this earth. In certain times and places, Buddhist teachings have been understood as directed toward the severance of all connection with the passions and desires of the world. They have also been seen as opposed to, or at least hindering, the advancement of civilization.

Buddhism, in fact, has penetrated deeply into the Japanese culture and psyche. It may be that the lack of advanced technology in some of the Buddhist nations can be attributed in part to the doctrine of transience; this, however, is only one aspect of the philosophy. Essential Buddhist teachings do not urge severance from this-worldly desires or isolation from all attachments. They preach neither resignation nor nihilism. Buddhist thought at its core is a teaching of the immutable Law, the essential life, the unchanging essence that underlies all the transience of actuality, that which unifies and gives rhythm to all things and generates the desires and attachments of human life.

Each of us consists of a lesser self and a greater self. To be blinded by temporary circumstance and tortured by inordinate desires is to exist only for the lesser self. To live for the larger self means to recognize the universal principle behind all things and, thus enlightened, rise above the transience of the phenomena of the world. What is this larger self? It is the basic principle of the whole universe. At the same time, it is the Law that generates the many manifestations of and activities in human life. Arnold Toynbee, describing the greater self as the ultimate spiritual reality of the universe, considers the Buddhist concept of the Law to be closer to the truth than notions of anthropomorphic gods.

To live for the greater self does not mean abandoning the lesser self, for the lesser self is able to act only because of the existence of the greater self. The effect of that relationship is to motivate the desires and attachments common to all human beings to stimulate the advancement of civilization. If wealth were not attractive, economic growth would not take place. If humans had not struggled to overcome the natural elements, science could not have flourished. Without the mutual attachment and conflicts characteristic of relationships between the sexes, literature would have been deprived of one of its most lyrical and enduring themes.

Although some branches of Buddhism have taught that people must try to free themselves from desire, sometimes even condoning self-immolation as a way of escaping this life, such an approach is not representative of the highest elements of Buddhist thought. Desire and sorrow are essential aspects of life; they cannot be eliminated. Desire and all it implies constitutes a generative, driving force. Nevertheless, desire (and the lesser self which it affects) must be correctly oriented. In striving to discover the greater self, the genuine Buddhist approach is not to try to suppress or wipe out the lesser self but to control and direct it so as to help lift civilization to better, higher levels.

Beyond Life and Death

Buddhism teaches that all things will pass and that death must be faced with open eyes. Even so, the Buddha was not a prophet of resignation but a man who had attained full understanding of the Law of impermanence. He taught the need to face death and change without fear, because he knew that the immutable Law is the source of life and of value. None of us can escape death, but Buddhism leads us to see that behind death is the eternal, unchanging, greater life that is the Law. Secure in the absolute faith that this is the truth, we can face both our own demise and the impermanence of all worldly things with courage.

According to the Buddhist Law, since life itself is eternal and universal, life and death are merely two aspects of the same thing. Neither is in any way subordinate to the other. There is a Japanese term, ku, that helps us to understand the ultimate, eternal life governing individual living and dying. Ku transcends the concept of space and time, for it signifies limitless potential; it is the essence from which all things are made manifest and to which all things return. Being everlasting and all pervasive, it surpasses the space-time framework. In our many discussions of eternity, Toynbee said that he felt in the idea of ku an approximation of what he calls the ultimate spiritual reality.

It is impossible to do justice to the nature of ku in so short a time, but I should like to make a few points. First of all, ku is not nonexistence. In fact, it is neither existence nor nonexistence. These two terms represent human interpretations of reality based on the space-time axes by which we ordinarily gauge our experiences and environments. Ku is more profound, more essential; it is a fundamental reality. Its nature may be illustrated by reference to the universal experiences of human development. The psychological and physical changes which take place as the individual grows from infancy to maturity are so great that the entire person seems to be transformed. Yet throughout this process, there is a self that unites mind and body, and remains relatively constant. We are not always aware of this self, which is manifested on both the physical and the mental planes, but it is the fundamental reality that lies beyond the realm of existence and nonexistence.

According to Buddhist philosophy, this enduring self is directly connected with the great web of cosmic life, and so it is capable of operating eternally now in the life phase and now in the death phase. This is why Buddhism interprets life and death as one. Since the lesser self is included in the greater self, each of us partakes of immutable cosmic life while living in the world of transience and change.

Breaking the Bonds of Desire

Unfortunately, modern societies seem to be swayed almost completely by the desires of the lesser self. Human greed has produced an immense, sophisticated technological system that has had devastating costs in environmental pollution and depletion of the natural resources of the planet. Attachment to things and desires and passions have led to the creation of huge buildings, sprawling transportation networks, and ominously potent weaponry. If the attitudes that have produced these things proceed unchecked, the self-destruction of humankind seems inevitable. Nevertheless, I remain hopeful that the current worldwide tendency to reflect on what is happening in society and to reclaim humane values are signs that we are at last searching for our own nature as human beings.

No matter how superb one’s intellectual abilities, a person is no more than an animal if he or she is dominated entirely by passions and the pursuit of the impermanent. It is now time for all individuals to look toward the enduring aspects of life and so live in a way that will bring forth true human value. How can this be done, now and in the future? Once again, Arnold Toynbee suggests a way. He referred to the greed and desires of the lesser self as diabolic desire; the will to become one with the greater self is loving desire. He insisted that people can control the former and give free rein to the latter only if they exercise constant vigilance and self-restraint.

In the next century, I hope that human civilization will break away from its bondage to the lesser self and move forward with an understanding of the permanent self that abides behind the fleeting existence of the material world. This is the only way for us to be worthy of our humanity and for civilization to become truly humane. The coming century should be devoted to respect for life in the widest sense, for the Law behind the universe is life itself.

The basis on which people choose to operate will determine the success or failure of civilization in the future. Will we elect to flounder in the mire of selfish desires and greed? Or will we walk safely on the firm ground of enlightenment, fully aware of the greater self? The realization of the dreams for the well-being and happiness of all depends entirely on our willingness to concentrate on the immutable, unchanging, powerful reality that is the Law and the greater life. We have arrived at the point where this decision must be made.

Our time is a transition from one century to the next, but it is also much more. It is a time when all of us must decide whether to become human in the richest, fullest sense of the word. At the risk of sounding extreme, it seems to me that in the past, people have rarely advanced much beyond the stage of an intelligent animal. Seven hundred years ago, Nichiren, the founder of the religious group of which I am a member, wrote of the “talented animal.” Considering the actions of human beings in the modern world, these words are particularly meaningful. It is my belief that we must become more than an intelligent or talented animal. It is time for us to become active in the spiritual sense as we struggle to attain an understanding of the greater self and of cosmic life.

Each individual person must find his or her own way. I have found mine in Buddhism, and with faith in its teachings, long ago I embarked upon the journey of life. Young people, now standing at an important turning point in history, are capable of building much for the good of humankind. In offering fragments of the wisdom of Buddhism, I will be very happy if what I have said is of assistance to them as they choose their paths to the future.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles