In the middle of the Joshua Tree desert, a solitary yellow, rotary phone sits inside a glass cabinet beneath the open sky. It isn’t connected to any wires, yet countless people have picked it up to “call” their loved ones—parents, children, partners and friends—who are no longer with them. Known as a “wind phone,” it has become a one-way line to those departed—a place to grieve and heal.

For Colin Campbell and Gail Lerner, the phone carries profound meaning. In 2019, their teenage children, Ruby and Hart, were killed by a drunk driver. When Campbell encountered a wind phone in October 2024, he found it so deeply healing that the couple installed their own in Joshua Tree—their children’s favorite place—as a gift for others who might need it.

The wind phone was first conceived by Itaru Sasaki, a garden designer, in Japan. After losing his cousin to cancer, Sasaki placed an old telephone booth in his garden in late 2010 as a way to continue their conversations. He told a Japanese TV station that, since his thoughts could not be relayed over a regular phone line, “I wanted them to be carried on the wind.”

When the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami devastated Northeastern Japan, Sasaki moved the phone to a hill overlooking the Pacific Ocean so that other mourners could “call” their loved ones. Since then, people from around the world have visited the original wind phone as a way to work through their pain. More wind phones followed, with nearly 300 now in the U.S.

The wind phone reflects humanity’s deep desire to connect with those we’ve lost. How can we work through the pain of parting with loved ones and transform it into hope? This is a question that has been asked since the beginning of time. In this feature, we will explore how our Buddhist practice can help us face with courage both loss and the lives we lead in their absence.Grief

Illuminated by Compassion

Death is inevitable. And while we may understand this point with our minds, when we are personally confronted with loss, it is one of the most difficult realities we face. While each person’s journey through grief is unique and deeply personal, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, a pioneer in near-death studies, distilled it into five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Whether we experience all of these feelings at once, move quickly through them or linger in one stage longer than others, the process requires patience and compassion toward ourselves and others.

Nichiren Daishonin showed profound empathy toward those who were grieving. Over the course of a year, he sent about 10 letters to the Nanjo family, who had unexpectedly lost their 16-year-old son, Nanjo Shichiro Goro. Just four days after Goro’s passing, Nichiren wrote in the “Letter of Condolence”:

With regard to the news of the demise of Nanjo Shichiro Goro: Once a person is born that person must die—wise men and foolish, eminent and lowly alike all know this to be a fact. Therefore one should not be grieved and alarmed by a person’s death; I know it to be so and teach others to do likewise. And yet when something like this actually happens, I wonder if it is not a dream or an illusion. (The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 2, p. 887)

Just a week later, Nichiren sent another letter expressing how he himself was having a hard time accepting Shichiro Goro’s death. Even near the end of his own life, Nichiren exerted himself to share words of comfort, standing with the family in their sorrow.

Ikeda Sensei describes this spirit to share in the suffering of others:

Someone battling destiny feels a gale raging through their heart. When we encounter such people, we should have the spirit to stand with them in the rain, become sopping wet with them and work with them to find a way out of the storm. In the end, that’s probably all another human being can do. (Learning From the Gosho, second edition, p. 146)

Grief is not something to be solved or fixed but rather something that can be assuaged when shared. From a Buddhist perspective, we can offer our support to those experiencing grief by offering our presence. Sensei illustrates this point with the image of a grieving mother.

Imagine a mother whose child has died, who is sitting in a daze on the roadside. Probably no words can heal her heart. … No one can share a mother’s grief. No matter how science advances, even though it can send human beings into space, it cannot assuage a mother’s sorrow. Maybe only the words of a woman who has been in the same situation can reach her.

What would the Buddha do in such an instance? Probably he would sit down at the mother’s side. And he might simply just sit there, not saying a word. Even with no exchange of words, the mother would sense the warm reverberations of the Buddha’s concern. She would feel the pulse of the Buddha’s life. Eventually, the mother would lift up her face and there before her eyes would be the face of the Buddha who understands all of her sorrows. The Buddha would nod and the mother would nod in reply.

Even without words, there is no greater encouragement than such heart-to-heart exchanges. On the other hand, even with a million words, nothing will be communicated in the absence of such heartfelt exchange. At length the Buddha would stand up, and the mother, as though following his example, would probably also rise. Then, together, they would advance forward one step and then another—their way gently illuminated by the light of the moon. The Buddha would continue to tirelessly offer encouragement until the mother could lift her head high, until she could determine to lead a life of great value for her dead child’s sake. (Learning From the Gosho, second edition, pp. 141–42)

Grief, then, is not a journey to be walked alone. When we sit beside one another with open hearts, we can find the courage to stand up again and move forward, even if only one step.

Until We Meet Again

The Buddhist perspective on the eternity of life gives us profound hope that those who have departed are not gone forever, that we will meet them again.

Nichiren encouraged grieving families with this conviction, telling Nanjo Hyoe Shichiro that she would definitely meet her late son again. Sensei explains this perspective of death:

From the standpoint of life’s eternity over past, present and future, when death separates people it is as though one of them has merely gone a short distance away. Like when someone goes to another country, making it impossible to see the person for a while. (Learning From the Gosho, second edition, p. 155)

This truth was personal for second Soka Gakkai President Josei Toda, who was once asked by someone whose child had died whether it was possible to reestablish a parent-child relationship in this lifetime. President Toda replied by sharing his own experience:

It’s impossible to say for certain whether you will meet your dead child during your lifetime. When I was 23, I lost my daughter, Yasuyo. All night, I held my dead child in my arms. I had not yet taken faith in the Gohonzon. I was beside myself with grief and slept with her in my embrace.

So we were separated, and I am now 58. When she died she was 3; so if she were alive now, I imagine she would be a full-grown woman. Have I or have I not met my deceased daughter again in this life? This is a matter of perception through faith. I believe that I have met her. Whether one is reunited with a deceased relative in this life or in the next is a matter of faith. (Learning From the Gosho, second edition, pp. 155–56)

President Toda then described how he was tormented by the pain of losing his daughter, his wife and the fear of his own mortality. It was only after encountering the Lotus Sutra in prison during the war that he finally resolved this “riddle of death.” That realization, he said, gave him the strength to lead the Soka Gakkai. Sensei builds on this, conveying that our bonds with loved ones are eternal:

We are connected by the invisible life-to-life bonds of the Mystic Law. We are the family of the Buddha of the Latter Day of the Law. We are eternal comrades. Transcending life and death, time and again we will be reunited in the place where we carry out our mission and renew our connection with one another. Life is hopeful, and death is hopeful too. Ours is a brilliant journey of life over eternity! (Learning From the Gosho, second edition, pp. 156–57)

In this way, Buddhism teaches that grief does not mark an end. Life and death are both part of an eternal journey, one in which we will find a way to be together again.

Chanting Empowers Healing

While it may seem at times that our pain will never go away, by chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo and engaging in Buddhist practice, we can transform it into a deeper understanding of life.

Sensei explains:

We should chant with the firm determination to definitely lead our children or our parents to happiness and complete fulfillment in life. Each Nam-myoho-renge-kyo we chant with such determination becomes a brilliant sun that illuminates the lives of our children or parents, transcending great distances and even the threshold of life and death. (Learning From the Gosho, second edition, pp. 153–54)

In this sense, our daily practice of gongyo and chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is the most profound offering we can make to our departed family members and friends. The fortune we accumulate through our Buddhist practice and SGI activities can be shared with them, ensuring that both the living and deceased become happy together. Sensei elaborates:

When we chant to the Gohonzon, we can engage in an inner dialogue. Our chanting functions like radio waves, connecting our lives with those of our deceased loved ones.

Dedicating ourselves to kosen-rufu, living out our lives to the fullest and becoming as happy as we can, for the sake of our departed loved ones and friends—this is the best possible way to honor their memory. (June 8, 2012, World Tribune, p. 5)

In this way, grief is not the end but the beginning of our journey to live fully. Sensei explains what happens when we continue walking the path of faith without retreating:

Though the sadness of loss may linger, there will be no sense of loneliness. Tears of sorrow will eventually turn into fresh commitment. Surviving family, loved ones and friends of the deceased will be able to look to the future with optimism. Family of the deceased, in particular, will gain the courage and energy to live to the fullest not only for themselves but for the deceased—striving not as mere “survivors” but as “successors” who share and carry on the deceased’s aspirations. (The Teachings for Victory, vol. 5, p. 146)

Through Buddhist practice, we can transform sadness into strength, loss into a vow to help others and grief into a deeper bond with our loved ones that transcends even death.

Living In Their Stead

The greatest tribute we can offer to those who have passed away is to live on joyfully in their stead, confident that our happiness will flow on to them. Sensei reminds us:

The important thing is that the surviving family and friends live with dignity and realize great happiness based on this conviction. Their happiness shows that they have conquered the hindrance of death and also eloquently attests to the deceased’s attainment of Buddhahood. (Learning From the Gosho, second edition, p. 157)

In Buddhism, the principle of the “oneness of life and death” holds that, if the living family members are happy, those who have died will become happy, too. Keeping our departed loved ones forever in our hearts, we can advance each day with the determination to attain Buddhahood in this lifetime. In so doing, we can ensure that those who have gone before us share in our boundless happiness.

On the following pages, Bryant Choa (p. 17) and Teiko Tsukui (p. 21) tell us about how their Buddhist practice helped them navigate loss.

One Path—Together With My Wife

Bryant Choa / Los Angeles

Living Buddhism: Thank you, Bryant, for sharing the story of you and your wife, ChoyShin, who you lost last March. Could you start by telling us how you met?

Bryant Choa: We met in 2014 through mutual friends in the SGI. ChoyShin and I married a year later and in 2016 moved to Los Angeles for her job. We welcomed our daughter, Aila, four years later, during the pandemic.

Aila was just 1 when we decided to go to Malaysia to visit ChoyShin’s family. Looking back, I’m so happy we took this trip because it was the last time my wife would return home while still healthy.

When did her illness begin?

Bryant: Soon after we returned from Malaysia. She began having stomach pain and difficulty eating. A biopsy revealed a rare cancer—affecting just one in 2 million. In a single surgery, her ovaries, uterus, spleen, appendix and large intestine were all removed in an effort to clean out as much of the cancer-ridden organs as possible. Doctors called it the “mother of all surgeries.” Despite this and thanks to everyone’s daimoku, the operation was a success.

In 2022, she lived with “no evidence of disease,” but by early the next year, the cancer returned.

During this time, ChoyShin never failed to take one step forward each day as she battled her illness. Within two years, she endured 30 rounds of chemotherapy and seven hospitalizations. Each chemotherapy round took several hours, draining all of her energy. She would take days to recover, but even then, she would approach the next round with a smile on her face.

She was a fearless lion who, whenever she encountered an obstacle, whether at work, with friends or family, always did three things without fail—brought the challenge to the Gohonzon, studied Ikeda Sensei’s guidance and read the Gosho.

She sounds like a person of incredible strength. What was her final chapter like?

Bryant: In January 2024, she was hospitalized in the ICU. It was the first time we heard from the doctors that recovery was conceivably no longer a reality. I’m a problem solver, but at this point, all I could rely on was my daimoku.

Around this time, ChoyShin and I had a hard conversation. I asked her whether she wanted to pursue further treatment. As much as I wanted her to keep fighting, she was exhausted. She told me, “I can’t decide, but what I do know is that I want to respond to my mentor and fulfill Sensei’s mission for kosen-rufu.”

What do you think she meant by that?

Bryant: It was her way to fight in her heart. Because she couldn’t regularly participate in SGI activities due to her illness, she turned to shakubuku. During hospital stays, she made sure to share Buddhism with all the hospital staff she encountered. The nurses, the transporters, the doctors, the interns, the receptionists—anyone and everyone. When she couldn’t speak, she would wave her hand to someone and instruct them to share Buddhism with the person or hand the person a message she had typed on

her phone explaining the meaning of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo.

She battled until the end with a smile. On March 1, her 37th birthday, friends filled her hospital room. Even on her last day, she was sharing Buddhism with every person who came through her door. On March 3, at 12 a.m., she passed away. She was absolutely victorious.

She certainly was. It must have been a truly difficult time. When and how did you start processing your grief?

Bryant: I had to start processing months before she passed. During that time, social workers would come into the hospital room and speak to me about her imminent departure. It was a strange feeling to prepare for someone’s departure while they were still there. I think that was the most difficult thing, sitting next to my dying wife and not being able to do anything to help her get better.

Early in the morning on March 2, the day before her passing, we spoke. By then, her cognitive function was severely impaired, and her memory was limited. But mystically, for 15 minutes, she talked like she used to, her eyes bright and clear. Speaking softly, she gave me several instructions, essentially her last wishes to me. One of them was, if the SGI asks me to support the organization in any capacity, that I should say yes. That’s what I did in April, when I was asked to be a district men’s leader. I remain determined to fulfill ChoyShin’s wish and to honor her legacy in this way.

Grief looks different for every person. What has that journey been like for you?

Bryant: My grief has been intense and messy. I remember the day after she passed, there was a kosen-rufu gongyo meeting, and I decided I wanted to go. I remember driving on the freeway, crying uncontrollably. I had many intense, often overwhelming emotions back then.

I staved off a lot of grief in the beginning by focusing on things that needed to be taken care of. But then, in a moment of quiet, the grief would hit me in waves, like a punch to the gut.

It was a jarring experience to be with someone for that long and then suddenly have them disappear from your life. Everything reminded me of her. Something as simple as the fan being on in the bedroom would trigger memories, and I would break down.

How did your Buddhist practice help you navigate this incredibly difficult time?

Bryant: The year of her passing, I had just graduated into the men’s division. There was a one-year training group called the Courage Group that I was invited to join. I felt so fortunate that I could take part in this group at a time in my life when, more than ever, I needed courage. I delved into chanting and study to find courage.

I also went to the Florida Nature and Culture Center (FNCC) that fall for my first men’s conference and sought guidance. I shared honestly that I had felt like I was a failure because of everything that had happened.

The senior in faith asked me what I thought ChoyShin would feel if she heard me say that. They shared that by fighting for the sake of other people’s happiness, I could find joy in my life again.

I’ve been chanting that way since and challenging myself to visit the men in my district and practice together with them. I’ve been striving to fight for others’ happiness as the path to my own.

You are now raising Aila on your own. What has that been like?

Bryant: Practically speaking, I chanted to find a good therapist or grief counselor and got physically healthier by exercising. I was doing it for Aila. I knew I couldn’t afford to fall apart, because then who would take care of her?

ChoyShin was the decision-maker in our family. Without her, I had to muster the courage to be the protagonist, especially when it came to Aila. And there were many decisions. Should she start school here or should we move back to New York? It’s an ongoing process for me as a parent, and I’m still learning. But I feel like I’m not trying to strategize anymore, and I’m trusting the wisdom gained through prayer to know what’s best. That has completely changed the way I approach my Buddhist practice.

Aila is now 5 and thriving. She just started kindergarten and actively participates in SGI activities, and in June, we went to the Family Conference at the FNCC together.

I’m always chanting for Aila to have a joyful and happy life despite all that has happened. And I feel like it’s happening before my eyes. She’s really coming into her own as a human being.

Aila remembers her mom. Sometimes as part of our bedtime routine, we pull up a photo of Mom and tell her about our day. I go first and then Aila. She loves looking at videos of her and ChoyShin when she was little. In those ways, we keep ChoyShin alive, and I hope she continues to learn about her throughout her life.

How do you feel like you’ve changed through this experience?

Bryant: It’s given me a tremendous amount of compassion for people who experience loss. Interestingly, the same year that ChoyShin passed, one of the members in my district was hospitalized. And I found myself on the other side, supporting them.

We always talk about fighting for other people’s happiness, but to actually apply that ideal and to experience it is a whole other thing. In a practical sense, supporting others moves me from despair to hope.

Do you have any advice for those who are experiencing grief?

Bryant: There were many moments when I wasn’t sure that I could go on, to be honest. But being able to chant and have someone to talk to is important. Having good friends in faith—people I can lean on and share how I’m feeling without fear of judgment—

has helped me process my grief.

I have a tendency to spiral inward, but I’ve learned that when I feel like I can’t move forward, that is the crucial moment when I have to reach out to others.

Whether I’m feeling anger, pain or worry, I now bare it all in front of the Gohonzon. Doing so is cathartic because I feel as if I’m having a deep dialogue with myself. Sometimes it’s painful because I have to address my own negative thoughts. But as time passes, and I’ve continued to chant and reflect, I have developed appreciation for moments of grief.

On a fundamental level, ChoyShin made a vow. We made a vow to meet at the exact moment in time when we did. And she decided that she would only be here for a little bit. But in that time, and through her passing, she taught me how to challenge my human revolution. Thinking of things this way gives meaning to her life; it gives meaning to the loss that we’ve had to experience. It helps me look ahead and think about how I can become better and stronger.

I don’t think I’ll ever fully get rid of my grief, but Buddhism has allowed me to transform it into something value creative for my life. Through this practice, I now truly believe I can transform anything, even unbearable tragedy and grief.

Your story will no doubt inspire many others. Do you have any determinations you would like to share for your future?

Bryant: Most of my prayer these days is about Aila. I’m chanting to be the best father I can be for her. I hope she grows up to be like ChoyShin—fearless and strong-willed.

As for myself, I’m chanting to have big dreams again. I’m also deeply praying to share Buddhism with someone who is really seeking and needing this practice and continue ChoyShin’s legacy in that regard.

Any parting thoughts?

Bryant: In November 2023, I attended my last young men’s conference at the FNCC and visited Ikeda Hall. One of Sensei’s poems stood out to me, and I shared it with ChoyShin at the time:

One path—

It is

a path of justice,

a path of happiness,

a path of freedom,

it is a path of fond memories

I walk together with my wife.

I want people to know that ChoyShin was victorious. I want to convey there was tremendous loss in her passing but also joy, happiness and victory that I will continue to build on, with her in my heart.

To Give Others Hope

Teiko Tsukui / Jacksonville, Florida

Trigger warning: This article discusses death by homicide.

Living Buddhism: Thank you, Teiko, for sharing your story with us. You lost your daughter 13 years ago. Do you mind taking us back to that time?

Teiko Tsukui: Lauren, our only child, was a student at the University of South Florida, which is about 4 hours away from Jacksonville. One weekend in early November, after having finished all of her exams, she came back home. That night, she had dinner with a friend, and then we enjoyed dessert together. I remember she was happy to be home. The following day, on November 2, 2012, her life was taken. She was only 20.

We’re so sorry to hear this. It must be difficult to talk about even now. Can you share what happened?

Teiko: Her ex-boyfriend, who had been stalking her, killed her and then killed himself in our house. I had been calling her all day because we had plans that evening after I got off of work. She hadn’t answered any of my calls. I came home to both of their lifeless bodies. It’s been 13 years, but when I think of it, I can remember everything as if it were yesterday.

I immediately called 911. They asked me questions, and I couldn’t think straight. “What’s your address?” they asked. I’m not sure I was making sense because they asked me to repeat it again and again. I called my local district women’s and chapter leaders next. Since my house was a crime scene, I couldn’t stay there. They took me to the closest member’s home where we just started chanting daimoku.

That seems unimaginable. What were the ensuing days like?

Teiko: The following day, Saturday, my husband and I started to make funeral arrangements. Then Sunday was our kosen-rufu gongyo meeting. I remember contemplating whether I should go, but I wanted to be there. Unexpectedly, the zone leader at the time was there, and I remember her so warmly hugging me. I was so touched by the care and warmth of the members, and I felt so much comfort even though my circumstances were so difficult. The next several weeks, many seniors in faith came to visit me. I have so much appreciation for them.

Actually, I couldn’t sleep for a time after she was killed. At 2, 3, 4 o’clock in the morning, I would get out of bed, sit in front of the Gohonzon and chant until the sun came up. My husband would wake up and chant with me. Chanting was the only thing that gave me a little hope. I would chant, start crying, chant, cry, chant. I chanted for her enlightenment and for her happiness. Somewhere in my heart, whenever I chanted, I felt that she was OK. I also read encouragement from Ikeda Sensei. Sensei’s words from Unlocking the Mysteries of Birth and Death really struck me.

In particular, there is one section titled “Violent or Accidental Death.” In it, Sensei writes:

Believers in the Mystic Law do not necessarily live long lives untouched by disaster. Death is a certainty. Therefore, it’s not whether our lives are long or short, but whether, while alive, we form a connection with the Mystic Law—the eternal elixir for all life’s ills. That, in retrospect, determines whether we have lived the best possible lives. When we strive continually to reveal our Buddha nature and to embrace others with the compassion of a bodhisattva, whatever we face in life then becomes fuel for our enlightenment. Disasters are then never merely disasters, and even a short life can be as fruitful as a long one. With faith, we can find infinite meaning in each event whether good or bad. (p. 97)

I chanted to truly understand what Sensei was saying here, but the reality was, for the first two or three months, I really questioned whether I wanted to live. I was grasping for hope. There were a mix of emotions. I felt so much anger—toward myself and toward the person who killed my daughter. I carried around guilt that I couldn’t protect her. I questioned whether it would be easier if I took my life, but I knew I couldn’t do that. So I chanted to understand the meaning of why I lost my only child when she was 20.

A relative, who also practices Buddhism, encouraged me to chant to my heart’s content. He told me that her entity is in the universe and that I would see her again in this lifetime or the next. And he told me that only I would recognize her because I’m her mother. That gave me hope—that I would see her again.

Grief is a process that takes time to navigate, even with our Buddhist practice. Can you tell us what that process has looked like for you?

Teiko: I would say it took me a year to start viewing her death differently. The more I chanted, the more I felt deeply that she voluntarily chose these circumstances. For my part, her death taught me how to practice Buddhism based on a vow. She taught me how to truly fight for kosen-rufu.

I was a newly appointed region leader at the time of Lauren’s death. So I visited the members and never stopped doing activities.

Even now, every time I chant, I hear her saying, “Mommy, don’t give up.” She gives me courage and determination to keep moving for the sake of kosen-rufu.

You mentioned earlier that you were moved deeply by the warmth and care of the members, but other people also came to your aid during this devastating time.

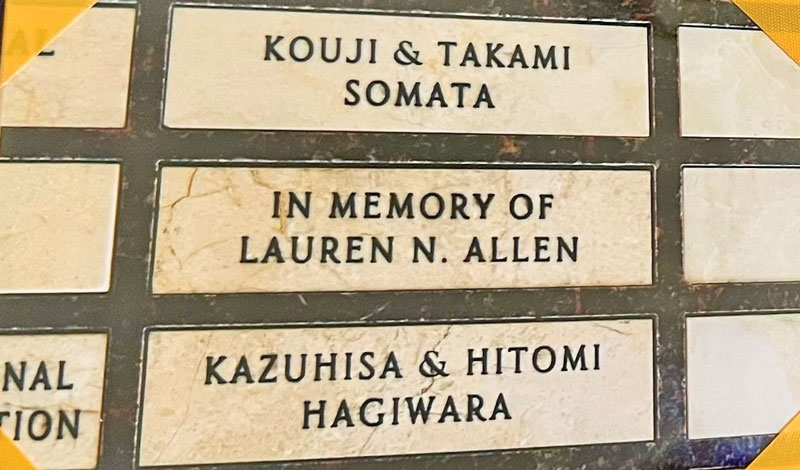

Teiko: Yes, my wonderful boss also really took care of me. When we lost Lauren, he told me to take as much time as I needed, and knowing how much my Buddhist practice meant to me, he donated a large sum of money to Soka University of America in Lauren’s name. If you go there, you can see a plaque with her name on it.

My boss also gave me the resources to see a therapist and join a group for parents who have lost their children. I went to both. While such groups play an important role in recovery, for me, it was difficult to find hope there. The place I could always find hope was when I went to an SGI meeting, so that’s what I did. I continued to support others and took Lauren with me in my heart everywhere I went.

You mentioned that through Lauren’s death, you learned how to practice Buddhism based on a vow. Can you share what that means to you?

Teiko: When I moved to the U.S. from Japan in 1986, I thought it would be temporary. I visited the Soka Gakkai headquarters in Japan before I left to share my new work assignment in the U.S. There, I was able to meet with the young women’s leader at the time. She repeated to me several times that I had a mission in America.

I didn’t understand what that meant. But now, I understand a little more. Somehow, losing my own daughter in this way was part of my mission, and part of Lauren’s mission too. It has helped me learn about the eternity of life and that no matter what unimaginable things you experience in life, you can find hope—you can stand up again. These are lessons I can pass on to others.

How has this experience shaped you?

Teiko: I have more compassion for others. I can feel other people’s pain and grief. I don’t know how many times I’ve attended a memorial service or funeral since Lauren’s death, but I can share my own experience with others about how this Buddhist practice has helped me to keep going, to not get stuck in sadness and to become happy. In doing so, I’m transforming my karma into mission.

Every morning, I go with my coffee into Lauren’s room, and I leave half of my coffee for her. She likes her coffee black. And I talk to her. I ask her how she’s doing today and update her on what’s going on here. She’s still an integral part of my everyday life.

Until the last moment of my life, I know I will experience difficulties. But true happiness, I now believe, is the inner strength to overcome anything. It is the strength to face everything without escaping, until the last moment, based on sincere prayer. Because I have the Gohonzon, I know I can overcome anything.

What do you want to say to those who are grieving a loss now?

Teiko: Stick with the SGI. Meet with members. Keep doing SGI activities. It will be the fastest way to relieve your pain. With faith, we can find infinite meaning in everything, whether good or bad.

Thank you for sharing your beautiful story with us. What are your determinations for the future?

Teiko: The other day, I met a young woman at a French bakery. I was speaking to her about peace, and her eyes opened wide. I gave her a Nam-myoho-renge-kyo card and asked her where she was from. She is from the Ukraine. She explained that her parents are still there and every day she worries about them. She is overwhelmed by concern for her family, for the safety and peace of the people in her country. I felt how important one-to-one dialogue is. Especially at this time, it is so important to give others hope.

Lauren had four best friends. They are like my daughters. They come visit me on Christmas or Mother’s Day and send me flowers on my birthday. I talk to them often. I feel like I have inherited those friendships from Lauren, and I’m continuing to talk about Buddhism with them with the hope that they will practice one day.

As a zone women’s leader, our team is uniting our efforts to introduce many young people to Buddhism, and I’m determined to raise many successors for the sake of the future. I have endless gratitude for Lauren for enabling me to deepen my vow for the happiness of others, as I advance kosen-rufu with her in my heart.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles