This is a translation of an installment of a Soka Gakkai Study Department series, published in the May 2024 issue of the Daibyakurenge, the Soka Gakkai’s monthly study journal.

In the sixth month of 1277, Nichiren Daishonin wrote a work titled “Letter to Shimoyama” (The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 2, p. 684), addressed to Shimoyama Hyogo Goro Mitsumoto, the steward of Shimoyama District.[1] Nichiren wrote on behalf of his disciple Inaba-bo Nichiei in Nichiei’s name.

Nichiei was a priest at Heisen-ji,[2] a temple founded by Shimoyama, who was a Nembutsu believer. Nichiei had been converted to Nichiren’s teachings by Nikko.

Nichiei lived in Shimoyama Village, only a few kilometers from Nichiren’s dwelling in Mount Minobu. After Nichiren moved to Minobu, Nichiei, hearing of his reputation, wished to meet him. He took the opportunity to accompany an acquaintance who was going to see Nichiren and was able to listen to him deliver a lecture. At first, having no intention of taking faith in Nichiren’s teachings, he found an inconspicuous spot outside the venue from which to listen (see WND-2, 684).

Upon becoming Nichiren’s disciple, Nichiei stopped reciting the Amida Sutra, one of the core scriptures of the Nembutsu teaching, and instead began reciting the verse section of “Life Span,” the 16th chapter of the Lotus Sutra. As a result, Shimoyama expelled him from the temple, which prompted Nichiren to write “Letter to Shimoyama,” a petition addressed by Nichiei to Shimoyama.

Its length, comprising almost 30 pages in the new edition of the Nichiren Daishonin gosho zenshu (The Complete Works of Nichiren Daishonin), suggests the degree of effort Nichiren put into it.

Ryokan Matches the Lotus Sutra’s Prediction of an Evil Priest

In the letter, Nichiren affirms that as a votary of the Lotus Sutra, just as the sutra predicts, he has called forth enemies who aim to stop him from spreading the correct teaching. He emphasizes that Ryokan, the chief priest of Gokuraku-ji temple revered by influential people in government, was an “arrogant false sage,” the third of three types of enemies the Lotus Sutra describes.

First, after explaining the five guides for propagation,[3] Nichiren traces the history of the spread of Buddhism in Japan beginning with the Chinese priest known as Ganjin.[4] He affirms that the superiority of the Lotus Sutra had been well established in Japan and asserts: “The way honest beginners should practice the Lotus Sutra is to devote themselves to the practice of the Lotus Sutra alone. Such persons are the true practitioners [of the sutra] who are honest” (WND-2, 687).

Next, Nichiren says that we have now entered the Latter Day of the Law—an age that calls for the propagation of the essential teaching of the Lotus Sutra. At this time, Bodhisattva Superior Practices will make his appearance, and the signs of this were already evident. He criticizes the scholars of various schools for making self-serving claims despite this. In particular, he points out that Great Teacher Dengyo, at the end of the Middle Day of the Law, established an ordination platform on Mount Hiei for administering the precepts of perfect and immediate enlightenment of the Lotus Sutra.[5] Thereafter, the entire nation of Japan abandoned the Hinayana precepts.[6]

Nichiren points out that Ryokan and priests of the Precepts school[7] nevertheless took up the Hinayana teachings that had been cast aside, misled the members of the court and warrior families, and declared themselves to be teachers of the nation. Nichiren deems them to be “the most grossly untruthful men under heaven” (WND-2, 689).

He then points out the Nirvana Sutra’s prediction of the appearance of evil priests, which states, “There will be monks who will give the appearance of abiding by the rules of monastic discipline” (WND-2, 690). He concludes that Ryokan perfectly fits the description of such an evil monk and warns that, in accord with the sutra, people who have been deceived by Ryokan will suffer the defeat of their nation and fall into the hell of incessant suffering.

What It Means to Be a Votary of the Lotus Sutra

Furthermore, Nichiren strictly denounces Kobo, the founder of the True Word school, and two leaders of the Tendai school, Jikaku and Chisho. Respectively the third and fifth chief priests of the school, Jikaku and Chisho distorted the teachings of Great Teacher Dengyo after his passing, claiming that the Mahavairochana Sutra is superior to the Lotus Sura. Jikaku interpreted a dream he had, in which he shot an arrow that struck the sun, as an auspicious omen testifying to the validity of his views. Nichiren, however, states to the contrary that the dream was an “omen foretelling that Japan would become a doomed nation” (WND-2, 698).

Even as the threat of invasion by the Mongol empire that Nichiren had warned of grew stronger, the people despised him while venerating priests of the established Buddhist schools. Consequently, he pointed out, they had become mortal enemies of the Lotus Sutra and of the heavenly gods and benevolent deities, which would lead to the downfall of the country. He states that by persecuting Nichiren, “the votary of the Lotus Sutra who is more precious than Shakyamuni Buddha, the lord of teachings” (WND-2, 710) and disparaging the Lotus Sutra, they will not be able to escape punishment. He also stresses that prayers offered by priests of the True Word teachings cannot avert a national crisis.

After this, continuing to write as Nichiei, Nichiren states that his claims are reasonable and the way in which the authorities exiled him without taking the time to conduct a thorough examination was unacceptable. He then explains that Nichiei had stopped reciting the Amida Sutra for the sake of Shimoyama and his parents. He concludes the letter by admonishing Shimoyama to heed Nichiei’s advice.

When Nichiren reveals that in the Latter Day of the Law he “is more precious than Shakyamuni Buddha, the lord of teachings,” he is expressing his awareness of his mission in life in the present time, the Latter Day. Regarding this, Ikeda Sensei writes:

This represents one of the most significant statements in Nichiren’s life and is the reason why “Letter to Shimoyama” is listed among his ten major writings.[8] It goes without saying that no one honored Shakyamuni more highly than the Daishonin. Yet, when viewed in light of the challenge of propagating the Lotus Sutra in the latter age after the Buddha’s passing, the votary of the Lotus Sutra of the Latter Day of the Law was incredibly important. …

The Lotus Sutra is the teaching that enables the enlightenment of all people in the Latter Day of the Law. That means that the votary of the Lotus Sutra must be a person who has the courage to stand up all alone and keep working to spread the correct teaching, undeterred by persecution and other hardships, in this slanderous age that is characterized by quarrels and disputes. The presence of such a votary is key to opening the way to happiness for all humanity in the Latter Day.[9]

This letter became the impetus for Shimoyama to become a follower of Nichiren. We also know that Nikko bestowed the Gohonzon on Shimoyama’s wife and child.

The Kuwagayatsu Debate

In the sixth month of 1277, the same month Nichiren wrote “Letter to Shimoyama,” he also wrote “The Letter of Petition from Yorimoto” (WND-1, 803). As he had done for Nichiei, Nichiren wrote this letter on behalf of his lay follower Shijo Kingo[10] in Kamakura and addressed it to Kingo’s lord Ema.[11] Around this time, Kingo found himself in a difficult predicament.

On the ninth day of that month, Nichiren’s disciple Sammi-bo had visited Kingo. At the time Ryuzo-bo, a Tendai priest from Kyoto, was living in Kuwagayatsu[12] in Kamakura. Ryuzo-bo was preaching day and night, and the people of Kamakura had come to revere him as they would Shakyamuni. While giving a sermon, Ryuzo-bo said, “If anyone among you has a question about the Buddhist teachings, please do not hesitate to ask” (WND-1, 803).

It was to that sermon that Sammi-bo invited Shijo Kingo, who, as a lay believer, observed in silence as Sammi-bo rigorously challenged and refuted Ryuzo-bo. This exchange came to be known as the Kuwagayatsu Debate.

A few weeks later, on the twenty-fifth day of the same month, Kingo received an official letter from his feudal lord Ema. The letter charged that while Ryuzo-bo was preaching, Shijo Kingo had burst in with a group of people carrying weapons, disrupted the debate and intimidated him. Moreover, it said that Kingo had disrespected Ryokan and Ryuzo-bo, whom Ema revered, thereby disobeying his lord’s orders. Finally, the letter demanded that Kingo write an oath pledging to discard his faith in the Lotus Sutra.

On the one hand, Shijo Kingo’s fellow retainers had long been jealous of him. And on the other, Ema had become a follower of Ryokan and was fond of Ryuzo-bo. In these circumstances, those who felt hostility toward Kingo used the debate between Sammi-

bo and Ryuzo-bo to slander Kingo and make unfounded accusations about him to Ema.

Kingo faced a tough decision: whether to carry through with his faith and lose his land and social status or, as Ema ordered, discard his faith in Nichiren Buddhism. In these most dire circumstances, Kingo valiantly chose to stay true to his faith.

In addition to immediately reporting his predicament to Nichiren, Kingo wrote down his vow never to write an oath discarding his faith and sent it to Nichiren along with the official letter he had received from Ema.

Along with his reply to Kingo’s report, Nichiren wrote this petition to Ema on Kingo’s behalf to submit in the event it was called for. That document, written in Kingo’s name, came to be known as “The Letter of Petition from Yorimoto.”

(To be continued in an upcoming issue.)

Written Oath—A Vow to the Gods and Buddhas

In Nichiren Daishonin’s writings, the word kishomon or “written oath” appears many times.

A written oath was a document in which one vowed to the gods and Buddhas to be truthful regarding one’s actions and statements. It also included a vow or promise made to the document’s recipient. The first part or preface, called maegaki, contained details of the writer’s vow. The following part, called shinmon (literally “god text”), listed the names of the gods and Buddhas to which the vow was being made. It constituted a declaration that if the writer did not uphold their vow, they could expect punishment from the gods and Buddhas they had listed.

People in medieval Japan believed that the gods and Buddhas created the real world and controlled everything in it. People lived with a constant awareness of these beings, sensing they were being observed by them and seeking their counsel.

People believed that if they lied or failed to uphold the vow they had written, the gods and Buddhas listed in the oath would punish them. More than a prayer or verbal pledge to a god we might hear someone utter today, writing such an oath was a formal and serious matter upon which one staked one’s life.

Discerning a Person’s True Nature

Ikeda Sensei: While this letter is in some ways an introduction to Buddhism and the Lotus Sutra, addressed to Shimoyama Mitsumoto in the voice of Nichiei, it also tells us that unless we know who is fulfilling the mission of the votary of the Lotus Sutra, struggling for the welfare of the people, we won’t understand the true meaning of Buddhism or the Lotus Sutra. That’s why the Daishonin pursues the crucial issue of clarifying the identity of the “arrogant false sages”—the third of the “three powerful enemies”[13]—who oppose the votary of the Lotus Sutra, as well as the identity of that votary who has triggered the onslaughts of all three of these enemies.

In “Letter to Shimoyama,” the Daishonin points out the errors not only of the Pure Land (Nembutsu) teachings but also the Zen, True Word and Tendai schools in Japan, clearly refuting the misguided assertions of each. In particular, he devotes a large section of this letter to denouncing the True Word Precepts priest Ryokan of Gokuraku-ji temple in Kamakura. …

Nichiren Daishonin fiercely attacked the fundamental evil that deceives and confuses people about the truth. He did this in order to clarify who is spreading and practicing the correct teaching in exact accord with the Lotus Sutra, out of a wish to bring true happiness to the people. We need to build a society in which people can discern the true nature of those who make a pretense of saintly virtue and not be led astray by deception and falsehood. The only way to do this is to encourage each individual to elevate their own spiritual condition.[14]

From the April 2025 Living Buddhism

References

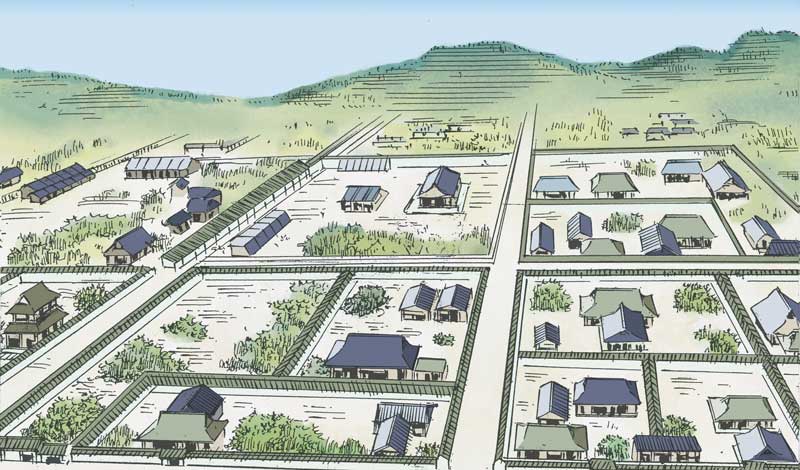

- Shimoyama District: Present-day Minobu, Minamikoma District, Yamanashi Prefecture. ↩︎

- A temple the Shimoyama family built to offer prayers for the happiness of family members and the repose of those who had passed. ↩︎

- Five guides for propagation: Five criteria to bear in mind while propagating Buddhism. They are: 1) the teaching, 2) the people’s capacity, 3) the time, 4) the country and 5) the sequence of propagation. ↩︎

- Ganjin (688–763): Buddhist monk of Tang-dynasty China and founder of the Precepts school of Buddhism in Japan. After studying the T’ien-tai and Precepts teachings, Ganjin attempted to travel to Japan. After five failed attempts to cross the sea and losing his eyesight, he arrived in Japan in the year 753. There, he established an official ordination platform, which was a place for conducting the ceremony for conferring Buddhist precepts. ↩︎

- The ordination platform at Mount Hiei is an ordination platform based on the Mahayana Precepts that Great Teacher Dengyo aimed to establish. “Perfect and immediate” expresses the teaching of the Lotus Sutra, which is both complete and without omission and enables people to immediately attain enlightenment. ↩︎

- Specifically, Hinayana precepts here refers to rules of monastic discipline. The Fourfold Rules of Discipline is so called because it divides the monastic rules into four sections; it sets forth 250 precepts for monks and 348 for nuns. ↩︎

- Separate from the Precepts school espoused by Ganjin in the Nara period (710–94). In the Kamakura period, amid a movement to revive the precepts, Eizon founded a new Precepts school called the New Doctrine school. ↩︎

- Ten Major writings: Ten treatises written by Nichiren and later designated by Nikko as his most important writings. In chronological order of writing, they are: 1) “On Reciting the Daimoku of the Lotus Sutra,” 2) “On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land,” 3) “The Opening of the Eyes,” 4) “The Object of Devotion for Observing the Mind,” 5) “Choosing the Heart of the Lotus Sutra,” 6) “The Selection of the Time,” 7) “On Repaying Debts of Gratitude,” 8) “On the Four Stages of Faith and the Five Stages of Practice,” 9) “Letter to Shimoyama” and 10) “Questions and Answers on the Object of Devotion.” ↩︎

- March 2016 Living Buddhism, pp. 31–34. ↩︎

- Also known as Shijo Yorimoto. “Kingo” derives from the Chinese name for his official position, which was Saemon-no-jo in Japanese. Yorimoto was his real name, but he was commonly known as Shijo Kingo and will also be referred to simply as Kingo. ↩︎

- Ema’s family belonged to the Hojo clan. The second Hojo regent was Hojo Yoshitoki. Hojo Yoshitoki’s second son was Tomotoki who was next in line to become the regent. Tomotoki was also related to Shimoyama Mitsutoki’s family. Tomotoki’s family was also known as the Nagoe family. Mitsutoki was suspected of plotting treason against the regent Hojo Tokiyori and was sentenced to confinement at the Ema residence in Izu Province (areas of present-day Kitaema and Minamiema, Izunokuni City, Shizuoka Prefecture), which was the former base of the Hojo clan. From then on, Mitsutoki’s family was called the Ema family. ↩︎

- Kuwagayatsu: Present-day Hase in Kamakura City, Kanagawa Prefecture. ↩︎

- hree powerful enemies: Three types of arrogant people who persecute those who propagate the Lotus Sutra in the evil age after Shakyamuni Buddha’s death, described in the concluding verse section of “Encouraging Devotion,” the 13th chapter of the Lotus Sutra. The Great Teacher Miao-lo of China summarizes them as arrogant lay people, arrogant priests and arrogant false sages. ↩︎

- March 2016 Living Buddhism, p. 34. ↩︎

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles