Reader advisory: The following piece addresses attempted suicide.

Living Buddhism: Karyn, thank you for speaking with us today. You began practicing Buddhism at 18, in 1975. Tell us how you found the practice.

Karyn Harvey: Well, I’m sorry to begin on such a sad note, but I was planning on killing myself at the time. The only thing holding me back was my mother, who was depressed and having trouble getting on her feet after a violent divorce. Until she did, I felt obligated to stick around and make sure she was all right. It was a friend of mine, an ardent Catholic, who told me about Buddhism. She didn’t know that I was suicidal, only that I was disillusioned and searching for the meaning of life. In any case, she put me in touch with a young woman in the SGI, who walked me through some recitations of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. I took it up as my daily practice without knowing there was an entire movement centered on it. A good thing too.

Why is that?

Karyn: I wasn’t just wary of organized religion. It was a total nonstarter for me. When the young woman I’d been put in touch with invited me to a meeting, I balked. This was the late ’70s and I’d already dodged, by the age of 18, a number of cults on my search for spirituality. All I knew was that, after years of searching, I’d found a practice that gave me hope and purpose in the face of various crises. Despite my reservations, I attended my first discussion meeting that year.

You were convinced right away?

Karyn: I knew something incredible was happening. The diversity of the people, of so many people coming together in such a relaxed, happy, familiar way, was not something I’d seen anywhere else in Connecticut. I wanted to be part of it, but couldn’t bear to be let down. To trust, for me back then, was a deadly serious affair. So, I began chanting on my own, asking myself, Can I trust this faith?

And your mind—or your heart—said yes?

Karyn: I know that dream analysis is not exactly the purview of Living Buddhism, but a week after my first meeting, I had a dream. I was walking through the halls of my old elementary school, alongside a gentleman who opened the door of each classroom for me to peek inside. Every door opened onto a different scene, all from my childhood, none of them happy.

Then he asked if I wanted to see what Buddhism was. I said yes, and he pushed open double doors, which opened onto a massive vista. Mountains, rivers, forests and lakes were lit by a brilliant sunrise over the mountain on which we stood.

I woke up and decided: I would receive the Gohonzon. That was the week I attended my first discussion meeting and brought 10 friends—my entire theater class and a few others. For me, the dream’s message was clear: We’re each born with karma and can wander forever through the rooms of our past, endlessly turning over their meaning without ever finding our way to happiness. I knew by then that Buddhism was about transforming karma. Practicing and spreading Buddhism, I decided, was what I was here on this Earth to do.

What a profound realization. How did the mentor-disciple relationship enhance your understanding of Buddhism?

Karyn: As I said, trust for me did not come easy. Not with family, friends, organizations—not with anything or anyone. I was fortunate, though. On October 8, 1980, at a big meeting in Washington, D.C., I saw Ikeda Sensei speak. Leading up to it, I chanted to be able to perceive his heart—his true character. And I remember getting there, and Sensei taking the stage and saying (paraphrasing here): “Thank you all so much for coming. For those who had long drives, I’m sure you’re tired. Feel free to nap. You can read what I say later, when you’re rested, in the World Tribune.”

And I could tell he really meant it. And I thought that was just delightful. He was thinking, first and foremost, about each of us. That said, I don’t think anyone took up the offer. I, for one, am glad I stayed awake. He said in part:

Of all the countries in the world, the United States is the symbol of freedom. Thus, I believe that this country has the mission to lead the entire world toward freedom and peace. If the domestic situation in the U.S. becomes unstable, there is a risk that the rest of the world will also lose its equilibrium.

When America truly moves toward peace, prosperity and progress, genuine global harmony will begin to take shape in our world, bringing security and assurance to people of good conscience everywhere.

For this reason, the U.S. must not lose direction or decline. Especially in looking ahead, I feel strongly that this nation needs a clear and firm spiritual core to secure a bright future.

This is why I must emphasize that those of you here in the United States who uphold faith in the Gohonzon, an unfailing spiritual pillar, have a great mission. (Tentative translation)

What did you do with that?

Karyn: I moved to Baltimore for my master’s shortly after and practiced with the young women in Washington, D.C., and Baltimore. I dove in fully with the organization there. I felt strongly that I needed to find my mission in society to respond to Sensei’s profound call to action.

Clearly, you did. Thirty-five years ago, you began working with people with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD). How’d you get into the field?

Karyn: I was interviewing for a nonprofit working specifically with people with IDD, many who’d been institutionalized, many for their entire lives. They were adults who’d been born at a time when the default was to institutionalize children with IDD.

I remember sitting in the lobby, waiting for the interview. People wandered in and out, and one woman approached me and began to pour out her life story.

I listened, then others came up and began talking to me. I felt powerfully drawn to all of them; I could feel their struggle, their hope and their pain. I knew at that moment that this was the population I wanted to work with. Frankly, I think I recognized myself in them—people who’d endured a lot. I soon learned they were often marginalized and forgotten.

I got the job and began working with them and immediately fell in love. They were some of the bravest and most open people I’d ever met.

That day, I knew: I’ve found my people. I’ll make a difference here.

What was the difference you wanted to make?

Karyn: Early on, I recognized that many of the people I was working with were suffering the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These were people who had endured far more abuse than I could even comprehend. Many had lived in institutions that had been widely condemned for neglect and abuse. In my first couple of weeks, I told my supervisor, “Let me do therapy with them.”

“You can’t,” he said flatly. “It doesn’t work with these people.”

What did he mean?

Karyn: He meant that these were people who could be managed but not healed and empowered. In his defense, he was echoing the sentiment of the entire field, which was focused entirely on managing behaviors. I felt convinced that the behaviors were by and large symptoms of something deeper. Like anyone who’s experienced trauma, these people needed someone who would listen to and support them. But having been labeled as having “problems” by the field, many had been dehumanized and humiliated for their expressions of pain. They were greatly misunderstood by those working with and directing services for them. To focus on their behavioral problems only increased the dehumanization.

Were you discouraged by his response?

Karyn: Actually, no. I felt indignant, like: I will not be stopped. I need to do whatever it takes to help people get what they truly need. It is their right. I made a point of spending time listening to each person I worked with, deciding that I would believe in them, in their Buddha nature, and support them as such to the limits of my own ability.

It sounds like your faith has fueled your work.

Karyn: Oh, it was and is the core of my work. The belief that each person is a Buddha was without a doubt the source of my advocacy at a time when so few agreed with it.

What did you do with your indignation?

Karyn: Took it to the Gohonzon. And then, I took it with me to Japan, on an SGI youth training course in 1987, where Sensei spoke. I expected that we’d hear a lot about the basics of faith and propagation but was surprised by how much he emphasized our roles in society. “Faith equals daily life” was the central message. Essentially, what I heard that day was: Whatever your chosen path, take it all the way. Your role as a Buddhist in society is critical to kosen-rufu.

By the time we’d touched down back in America, I’d decided to enroll for my Ph.D., to become a voice my field would listen to on behalf of the people I cared about. The following year, 1988, I was accepted to a Ph.D., program for applied developmental psychology at the University of Maryland.

It must have been wonderful to study with others working to pioneer new frontiers in the field.

Karyn: You know, it’s unfortunate, but I encountered the same prejudice at school as I had in the field. Many teachers asked me many times why I was entering a field in which therapy was considered impractical. I took my frustration to the Gohonzon and kept working.

Around the middle of the program, I got a call from my former supervisor—the one who’d told me that the work I wanted to do was impossible. He shocked me with his words: “I think you were right. We need to try a new approach, and I need your help to try it.”

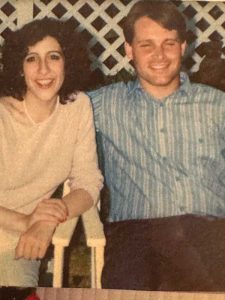

At this point, I had two little children—a son and a daughter—who’d been born in the first few years of my Ph.D. program. (I’d met my husband in 1986, the same week I began working with people with IDD—a total breakthrough week for me!) I was the first person permitted to take the program part time, which was wonderful for me and the kids. But kids and schooling are expensive, and what I really needed, was a part-time job.

“I have an internship for you,” my former supervisor continued.

“Oh great,” I said.

“Paid,” he continued. To my knowledge, none of my fellow Ph.D. students had yet landed a paid internship, though a one-year internship was a requirement of the program.

The opportunity seemed practically tailor-made for me. I was overjoyed. I took it and found myself working, for the first time in my career, with someone who believed in what I was doing.

At some point, you take things up another level.

Karyn: True. I should say that throughout all of this, I was chanting and sharing the practice with many friends. But at some point, I realized that I had to base everything on faith and practice even more. For me, it was 2002, when the U.S. waged war on Iraq—a massive bombing campaign that killed, maimed and displaced enormous numbers of people. I knew that I had to practice with everything I had. This also meant striving harder in my work to have an impact on my field.

I changed jobs and started working with a close-knit team, trying new and creative ideas grounded in compassion and developing frameworks and practices that we saw truly help people. At the heart of healing, I noticed, was the development of a positive self-identity. And its formation was possible only once a sense of safety, connection and empowerment had been created. We found that the behaviors that so many in the field felt they had to “manage and control” often resolved themselves when people were treated humanely. I knew this was important to share, so I set to work writing my first book.

A book. How’d that go?

Karyn: Honestly, only a small group of people read it. But the fact that I’d actually written it, that it had actually been published, was extraordinary to me. I hadn’t yet made any deep inroads, but I’d done something new and now knew that it could be done. In 2011, I began writing a second book and this time got a new publisher. Published in 2012, it gained a big readership among professionals. Suddenly, I was being asked to give talks, trainings and consultations across the country and even in other parts of the world. Everywhere I went, I was surrounded by people who were interested in and believed in the approach I was sharing. Of course, there was still some pushback, but I knew I was getting the word out about the humane treatment needed for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

After such a long battle, this must have been exhilarating. And now?

Karyn: Every day I am still doing this work. I also wrote a third book, published by a great publisher, that is being widely read as well. One of my greatest joys over the years has been sharing Buddhism with my friends and colleagues and watching them take up the practice and transform their lives. It’s startling to remember, now and again, how dark and hopeless my inner world once was. Today, my life is exhilarating! I have endless opportunities to teach and share on behalf of a population that deserves dignity and happiness as much as anyone. Truly, each day is a joy!

What would you say to the youth?

Karyn: I think I can’t talk about the youth without mentioning the pandemic, which totally disrupted their lives. Many young people are still dealing with the psychological effects of the pandemic, which has contributed, among other things, to lots of anxiety. I want to say that I see myself—my younger self—in many of them. I want to say: You can rely on this Buddhist practice. On this organization. On this philosophy and on Sensei. Believe in yourself and in what you’re doing each day. If you have a vow for kosen-rufu at the core of your life, you’ll definitely see your dreams come true. In fact, you’ll see things happen even beyond your current dreams, more than you even imagined! Keep going and never give up!

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles