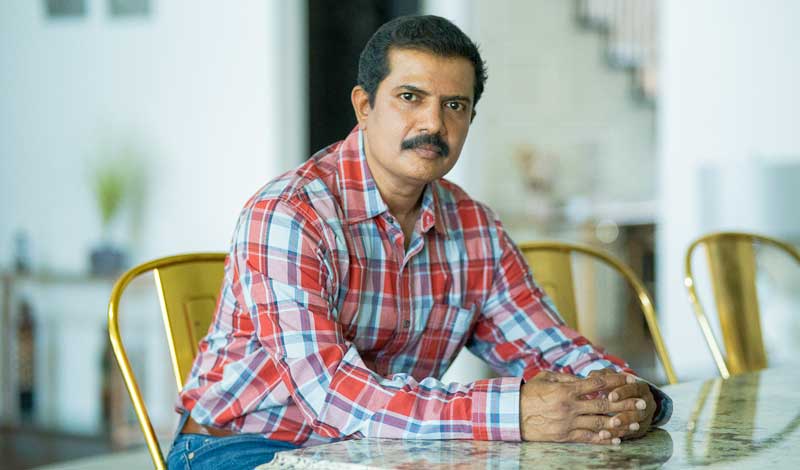

by Kiran Malige

Dallas

Visitors flooded our home the following day to confirm the news for themselves. From morning to evening, they came—friends, neighbors, family, kids—flowing by the dozen through the home and spilling into the yard. We welcomed the company—needed it, really—and yet, it made me restless. Speaking to one person after another, I began to sense that I was the only one who was not managing to mourn. My mind, you see, was racing, anxiously from thought to thought to thought.

Just one day earlier—June 12, 2015—my 4-year-old daughter, Prakya, had woken with the rest of us and left with her mother and brother for a public pool. I’d left for work by then and was there when I got the call, shortly after noon, from my wife in hysterics: Prakya had slipped from view for mere moments at the pool; she’d stopped breathing and couldn’t be brought back to consciousness. By evening, the doctors had pronounced our daughter dead.

Speaking with our curious, baffled, mourning visitors, I felt a chill spreading within. To grieve now, I knew, would undo me. Instinctively, my mind grasped for hard facts and realities—the stuff that plans are made of. The problem was, there was nothing to grasp; we had neither the death certificate nor our daughter’s body. I could plan neither the funeral in Dallas nor the ceremony in India. Moment by moment, the need to plan a future grew desperate, and I felt myself falling apart.

It was midmorning when my friend Mallik arrived, with his wife and two girls. His wife sat with mine while I spoke with him. His daughters, who yesterday would have played with Prakya, sat quietly with their mother.

“I’m so sorry,” he said simply, and it took me a moment to realize that was all he’d come to say. It occurred to me then that he was among the very few who hadn’t come with a question. Until then, I hadn’t realized just how tense I’d grown. Warming up, I began voicing, amid the foot traffic, what was on my mind: the impossibility of preparing even for the immediate future. He listened and now and then posed a question, helping me consider what was actually within my control. His calm, amid the emotional bustle, reminded me of something I knew about him—that he was a person of faith—a Buddhist. Actually, in recent months, that fact had dawned on me several times, and I’d begun asking when and where I could join a meeting, though I hadn’t yet made the time.

“There’s one coming up,” he said before he left. “Why don’t you come?”

Over the next few days, our affairs fell into place: We received the certificate and our daughter. In July, we traveled to India to spread her ashes, returning toward the end of the month. I called Mallik as soon as we got home to Dallas. That September, we went

together—my family and his—to our first Buddhist meeting, where I was won over, right away, by the people.

I think it may be common practice, even instinct, to hold a stranger’s suffering at arm’s length. But the people of the SGI are different, aren’t they? Within my district, I found a willingness—an eagerness, even—to shoulder a burden together. I did not fully grasp the concept of “turning poison into medicine” right away but understood that everyone I spoke with had their own experience of doing just that.

Of course, my grief did not vanish. Now and then, a desperate feeling washed over me, a sudden memory of my daughter. For her, I’d been the person she could depend on for anything—to uplift her when she was sad, to be there when it mattered most. When this feeling struck, I began to chant in my heart. I called a friend or read a book by Ikeda Sensei. One I’d been gifted was titled Unlocking the Mysteries of Birth and Death. A portion reads:

Death is a certainty. Therefore, it’s not whether our lives are long or short, but whether, while alive, we form a connection with the Mystic Law. … That, in retrospect, determines whether we have lived the best possible lives. When we strive continually to reveal our Buddha nature and to embrace others with the compassion of a bodhisattva, whatever we face in life then becomes fuel for our enlightenment. Disasters are then never merely disasters, and even a short life can be as fruitful as a long one. With faith, we can find infinite meaning in each event whether good or bad. (p. 97)

As I chanted for my daughter’s happiness, I began to see myself as she had seen me—as someone strong, dependable, wise and kind. This was painful, but as I moved through the pain, I began to see something else as well: That I could become such a person for the world. I began to understand what the SGI was all about: Endless opportunity to deepen one’s character.

That October, my wife and I received the Gohonzon. The following summer, I accepted district leadership, determined to spread the joy of turning karma into mission throughout the land. As a district, we began reaching out to those who hadn’t come out in a long time and chanting together with them. Slowly, the district grew, as old friends recalled the joy of practicing in community and new ones discovered it for the first time.

I’ll never forget one visit I made in 2020 with a gentleman taking his first steps into the practice. Burdened with regrets about a past relationship, he listed them one after another. Listening, I shared about my daughter and the feelings that had come with her death. “Our experiences are different,” I said, “but I’m no stranger to regret. Buddhism has made it possible for me to live without regrets, to turn all poison into medicine. It’s taught me to live in the present, from this moment on.” I was a chapter leader by then and was experiencing the tremendous joy of doing visits and shakubuku. In fact, we all were—the whole chapter; over the course of five years, we nearly doubled our membership.

In my work, in my family, in my community—in everything I do, I can say I’ve grown stronger, wiser, more open and more kind. I feel deeply that it was my daughter’s mission to awaken my family to this practice. Every year, twice a year, we celebrate her life—on her birthday and on the day of her passing. But it’s better said that I celebrate her life every waking moment of the day, because it turned me outward and taught me to love the world the way I loved Prakya—to strive to be for the world what I once was for her.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles