Ikeda Sensei’s serialized novel The New Human Revolution chronicles the history of the Soka Gakkai following his inauguration in 1960 as its third president. It carries practical guidance on how to expand our movement for kosen-rufu and hundreds of experiences of inner transformation. Sensei appears in the novel as Shin’ichi Yamamoto. The following takes place in 1978.

Installment 1

The ability to engage in dialogue is one of the most outstanding human attributes. Dialogue expresses our humanity.

Through talking with one another, hearts open, mutual understanding develops and friendship spreads.

True dialogue is not putting on a facade and spouting empty, flowery rhetoric. Dialogue is interacting life to life, just as we are, as fellow human beings, with sincerity, conviction and patience.

A Buddhist sage[1] once said: “The voice carries out the work of the Buddha” (“The Sacred Teachings of the Buddha’s Lifetime,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 2, p. 57). The Lotus Sutra—extolled as “the king of sutras”—is a dialogue among Shakyamuni Buddha and his disciples. Nichiren Daishonin wrote his treatise “On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land” as a dialogue between a host and a guest.

Dialogue has the power to encourage and engender hope. It is a wellspring of courage and a fresh breeze of revitalization. It is a bridge connecting people’s hearts.

On the afternoon of October 10, 1978, Shin’ichi Yamamoto and his wife, Mineko, met with the eminent U.S. economist John Kenneth Galbraith, his wife, Catherine, and others accompanying them at the Seikyo Shimbun Building. Dr. Galbraith, professor emeritus at Harvard University, had written many renowned works, including The Age of Uncertainty.

Installment 2

Young women’s division representatives applauded the tall, silver-haired economist as he stepped from the car at the building’s entrance.

Born in 1908 and now almost 70, he still had a fire in his eyes and exuded youthful vitality.

People with a passion for fresh challenges remain ever young.

Reaching out to shake his hand, Shin’ichi said: “You must be very tired from your long journey. Welcome. I am honored to meet you.”

Dr. Galbraith had left the United States on September 10 for a trip to Italy, France, Denmark, Belgium, India, Thailand and now finally Japan, meeting with dignitaries and lecturing along the way. He showed no signs of fatigue, however, and said with a bright smile: “I have been looking forward to meeting you too. This warm welcome has revived me.”

Holding a bouquet of flowers from Mineko, Catherine Galbraith said: “With these flowers from Mrs. Ikeda and the bouquet of beautiful smiles filling the courtyard, how could anyone fail to be energized!”

Everyone smiled even brighter.

“Let’s have a wonderful dialogue for the sake of humanity’s future!” Shin’ichi said as he led the delegation into the building.

After graduating from a Canadian university, Dr. Galbraith earned his doctorate at the University of California, Berkeley, later becoming a professor at Harvard. He went on to serve as the U.S. ambassador to India, the president of the American Economic Association and as an economic advisor to U.S. presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson.

He wrote numerous books, including The Affluent Society, The New Industrial State and Economics and the Public Purpose. His Age of Uncertainty had just been published in Japanese that February and had become a bestseller, so his name was well known in Japan.

Installment 3

Dr. Galbraith was over 6 1/2 feet tall. Shin’ichi barely came up to his shoulder as he escorted him through the building. When they arrived at the meeting room, they exchanged greetings again.

Looking up at his guest, Shin’ichi stretched his hand toward his head and said with humor: “I’m sure you’ve already seen Mount Fuji, Japan’s tallest mountain. I welcome you Dr. Galbraith, a true master of economics, and will engage in our dialogue as if gazing up at Mount Fuji.”

The professor smiled. “I am not nearly as dangerous as my size suggests!”

Everyone laughed. Shin’ichi then quipped: “Tall people have a good overview of their surroundings, but short people can see the ground more clearly. So perhaps by combining these two perspectives, they can find some overall ‘certainty.’”

Several businesses had invited Dr. Galbraith to Japan, and the representatives of one publishing company, including its president, accompanied him. They smiled as they listened to the friendly banter.

During the dialogue, Shin’ichi and Dr. Galbraith each brought up various topics and shared their thoughts on them.

Kicking things off, Shin’ichi said: “In modern times, people seem to focus solely on life and view death as something separate. But if we ponder the meaning of life, seek happiness and think about the state of our society and civilization, it is extremely important to look at death, explore it and come to a sound understanding of both life and death.

“Buddhism teaches that life is eternal. In other words, when we die, our lives merge with the universe and continue in a latent form to reemerge into an active state under the right causes and conditions. Our deeds, words and thoughts are carried on as our accumulated karma.

“So, my question to you is, what do you think happens after death?”

If we don’t understand death, we cannot understand life.

Installment 4

Dr. Galbraith responded in a slow, measured way.

“That is a very important, fundamental question, full of mystery and extremely difficult

to answer. I do not know what happens after we die. I do, however, believe in the continuity of existence. And at my age, I will not have to wait long to find out!”

Even on this solemn topic, he retained a sense of humor. Laughter facilitates communication.

The atmosphere can easily become heavy when discussing serious and important subjects. Sensing the economist wished to lighten the mood, Shin’ichi Yamamoto appreciated his consideration.

The two discussed many topics, including their favorite books and views on marriage. On books that had inspired them the most, both mentioned the works of Tolstoy. Dr. Galbraith was delighted.

Tolstoy had observed: “Communication with good people brings happiness.”[2]

As they talked about life, when asked about his personal motto, the economist said: “I haven’t a simple motto, but I have a firm rule. It is, ‘Work now, and don’t expect to finish.’ I always say that to myself.”

Shin’ichi thought those were wonderful words to live by.

He imagined that by “work now,” Dr. Galbraith meant to work wholeheartedly each moment, with grand ideals yet a firm grasp of reality. And by “don’t expect to finish,” he perhaps meant not being satisfied with easy results but always striving for improvement.

When asked what words inspired him, Shin’ichi said: “The greater the resistance waves meet, the stronger they grow.”

Installment 5

Shin’ichi then asked Dr. Galbraith about the saddest event in his life.

“It was losing my son. If I may say so, he was remarkable, deeply intelligent. He died of leukemia when he was very young.”

This reminded Shin’ichi of when he had asked Arnold Toynbee the same question. The historian said with a pained expression that it was when his son took his own life. Shin’ichi would never forget the way he sat there motionless, his eyes damp and his fingers interlaced in front of him as if in prayer.

Even the most eminent among us cannot escape sorrow. We struggle with and live on through storms of fate. No life is without challenges. The key to happiness is whether we let our suffering defeat us or use it to develop, improve and become stronger.

The economist also spoke of his grief at the assassination of John F. Kennedy, who had appointed him his ambassador to India.

The conversation then moved to U.S.-China relations, and from there to a discussion of the different leadership styles of China’s Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai and India’s Jawaharlal Nehru.

When Shin’ichi mentioned that he would be visiting India the following year, Dr. Galbraith encouraged him to go to Punjab, a region spanning northwest India and eastern Pakistan. It was famous as a cradle of ancient civilizations, he explained, being home to the ruins of Harappa, but it had also developed significantly.

Catherine Galbraith noted that the state of Kerala in southwest India was also undergoing impressive development. She had supported her husband during his tenure as ambassador and was extremely knowledgeable about the country.

Women, because of their practical daily life experience, often grasp the reality of a society most accurately.

Installment 6

Dr. Galbraith published a chronicle of his time in India titled Ambassador’s Journal: A Personal Account of the Kennedy Years.

In the introduction, he describes Catherine’s efforts: “The household, entertainment, a wide range of protocol activities, concern for the problems of the American community [in India], association with wives and families of my Indian and diplomatic associates, cultivation of the arts and representation of the Ambassador at a succession of functions during my absence were all accomplished by my wife. She even found time to learn Hindi to the point of making a quite acceptable speech in the language.”[3]

He had known little about this, however, until he read her personal recollections, published in the May 1963 Atlantic Monthly. He confessed to being rather astonished at the scope of her activities.[4] The article, titled “‘Mother Doesn’t Do Much’: The Ambassador’s Wife in India,” appears in the appendix of Ambassador’s Journal.

Catherine described her activities in detail. She explained how she had supervised not only the staff but also looked after their families. Numbering around 50 altogether, they adored her as “the mother of us all.” She cared for them when they were sick, helped settle quarrels and strove always to be fair and impartial. She served the staff tea every day, presented the wives with new saris on Indian holidays and gave everyone gifts at Christmas.

She also managed the ambassador’s events, from greeting guests to organizing meetings, interviews, receptions and dinners. And she accompanied her husband on official visits and sometimes had to speak on his behalf on short notice.

While seeing to all these duties, she also raised their children.

Nichiren Daishonin likens the teamwork of a couple who shares the same conviction to the two wings of a bird or the two wheels of a cart, teaching that they can achieve anything.[5]

Installment 7

The publisher of the Japanese translations of The Age of Uncertainty and others of Dr. John Kenneth Galbraith’s writings said he would like to ask something connected to their discussion of India.

What did they think Japan should do to help reduce the economic gap between advanced industrial countries and developing countries? In other words, how should Japan address the North-South divide?

Dr. Galbraith responded without hesitation: “The first is that Japan, as a country now belonging to the community of rich countries, has a moral obligation to contribute some of its well-being in assistance and capital to poor countries.

“The second is to contribute through agriculture. With its rice farming know-how, Japan can offer instruction to developing nations partly because there is an ease of association between Asian cultures that would make its instruction readily acceptable. This is an extremely practical way for Japan to contribute.

“In poor countries, nothing is so important as food, such as rice and wheat, and water. We first need to consider what the people in those countries need most. What are your thoughts, Mr. [Shin’ichi] Yamamoto?”

“The things you have mentioned are very important. I am concerned, however, that simply providing one-sided economic aid of goods and technology may lead to a solely interest-based relationship; it may establish a hierarchy between ‘donor’ and ‘recipient’ countries. There is also the danger that it will undermine the pride and self-reliance of people in the recipient country.

“It is therefore essential to build mutual trust. This requires ongoing grassroots educational and cultural exchange. I believe and have consistently maintained that only by patiently continuing such efforts over 10, 20 or 50 years can we open the way to lasting trust.”

Installment 8

Dr. Galbraith said that he agreed completely.

The conversation was in full swing.

Next, they moved on to discuss The Age of Uncertainty, which asserted that today’s world no longer had any solid guiding principles. Shin’ichi said he strongly concurred.

Many serious issues threatened the survival of humanity, such as war, nuclear weapons, pollution, dwindling resources and overpopulation. But people seemed unable to find a guiding principle or philosophy to tackle these challenges with.

Shin’ichi was determined to do whatever he could to avert these dangers. Above all, he vowed to ensure a third world war would never happen.

He firmly believed that the Buddhist ideal of respect for the dignity of life was just such a fundamental guiding principle and that if people the world over embraced it, they could eliminate these threats.

But no matter how convinced he was of the superiority of the Buddhist teachings and how unshakable his faith in them, for them to be broadly accessible to the public he knew it was essential that scholars come to validate and appreciate their greatness too. Without efforts to win public support, a religion will easily lapse into dogmatism and self-righteousness. That’s why Shin’ichi held dialogues with world thinkers.

He asked Dr. Galbraith, “What guiding principles do you think we need as we search for certainty in this ‘age of uncertainty’?”

The economist noted that in the past, the ideas of Adam Smith and Karl Marx had been regarded as great certainties, but errors in those ideas became apparent over time, and they could no longer be relied upon as certainties. In fact, he said, all human endeavors need constant amendment to make life more secure, peaceful and intelligent. Perhaps accepting that way of thinking is ultimately a guiding principle, he added.

Installment 9

Dr. Galbraith worried that people’s obsessions with ideology often caused them to look away from reality, avoid critical thinking and judge things by placing them in narrow theoretical frameworks.

Shin’ichi also opposed making decisions based on predefined external norms such as ideology or theory. Doing so could have the reverse effect of shackling the human spirit.

“I believe it is important to recognize that we human beings, the ones making the decisions, are defined by uncertainty, full of contradictions and inner conflict, our minds changing moment by moment,” he said. “Therefore, I consider it vital for us to elevate our humanity and grow as human beings so that we can always make sound decisions. To do that, we need a universal philosophy of life that enables us to realize such inner growth, and we of the Soka Gakkai have found that in the teachings of Buddhism.

“In short, we can describe the correct teaching of Buddhism as the fundamental Law, eternal and unchanging, that permeates all phenomena and the universe. We possess within us an inexhaustible font of wisdom, and Buddhism teaches how we can uncover and tap it. We call the process of unlocking our potential rooted in this law of life ‘human revolution.’

“I have discussed the problems facing humanity with Arnold Toynbee, the French thinker and activist André Malraux, and others. They agreed with me that a trend toward spiritual transformation, toward human revolution, in line with Buddhist principles, represents a dynamic philosophical movement that will usher in a brighter future for our world in the 21st century.”

Dr. Galbraith responded candidly: “My understanding of Buddhism is quite limited. That is why I find your remarks so thought-provoking.”

His words were humble. Those of great scholarship possess a sincere spirit for learning and a thirst for truth.

Installment 10

Shin’ichi Yamamoto went on to discuss the role of Buddhism.

“Politics, economics and science all originally seek human happiness, but they primarily focus on external factors such as social systems and living conditions. Religion, in contrast, concentrates on finding happiness within. It can be said that human happiness depends on developing both a solid inner foundation and favorable external conditions.

“Human beings create and develop all institutions, systems and fields of learning. Reforming our societies therefore hinges on reforming the hearts of human beings, the protagonists of change. I believe this is the role of the higher religions, especially Buddhism.”

Dr. John Kenneth Galbraith leaned his tall frame forward, listening intently.

“That is a very important point,” he said, nodding. “As you say, the aim of everything is human happiness. If I could expand on this a bit, I would add that while politics, economics and science have made rapid progress in their respective areas, somewhere along the way, they have become ends in themselves, unrelated to human contentment, happiness and peace. This seems to me a dangerous development.”

“Yes, precisely!”

The economist went on to stress the need for a philosophical system that can give a unity of purpose to the divergent tendencies of modern intellectual life, directing them back toward such core human aims as happiness and peace.

“As an economist,” he said, “I aspire to contribute in any way I can to human happiness. After listening to you speak, Mr. Yamamoto, I would really like to join you on a visit to India, the land of the Buddha. It would be wonderful if we could continue this conversation someday in Sarnath.”

Sarnath, also known as Deer Park, is where Shakyamuni delivered his first sermon after attaining enlightenment.

During their nearly two-hour meeting, Dr. Galbraith and Shin’ichi agreed on many points.

Sincere and honest dialogue engenders mutual understanding and forges human ties.

Installment 11

In an article titled “My Japan Diary” in the Japanese magazine Bungei Shunju’s April 1979 issue, Dr. Galbraith wrote about their dialogue: “We discussed China and the Soviet Union, nuclear armaments, aid for developing countries and Japan’s special responsibilities in this respect. We had a lot of back-and-forth, and we agreed on almost everything.”

Though a reunion in India did not happen, Dr. Galbraith and his wife visited the Seikyo Shimbun Building again in October 1990, and they had another opportunity to speak.

On that occasion, Shin’ichi and Dr. Galbraith lost track of time talking about peace, economics and prospects for a new international order toward the 21st century. They also shared personal stories about their interactions with various world leaders.

The fruit of friendship ripens when we treasure each conversation, speak sincerely and foster mutual respect and understanding.

In September 1993, Shin’ichi gave his second lecture at Harvard University, titled “Mahayana Buddhism and 21st Century Civilization.” Dr. Galbraith made time in his busy schedule to attend and serve as a commentator.

He described Shin’ichi’s lecture as a “marvelous account of the path that we all share in hoping, all share in wishing, [that we] may be on the road to peace,” acknowledging the spirit of peace central to Buddhist thought.

Installment 12

The day after the lecture, Shin’ichi visited the Galbraiths, accompanied by his wife, Mineko, and eldest son, Masahiro. The couple lived in an elegant brick home with pink trim in a quiet residential area near the university. Squirrels scampered through the trees in the yard.

Though Dr. Galbraith was almost 85 at the time, it was a lively conversation.

Expressing his admiration for Shin’ichi’s efforts to build peace through dialogue, the economist shared that he, too, had tried to live his life with a fervent and abiding conviction and desire to put an end to the cycle of war.

They went on to discuss the best way to show people how to lead truly fulfilling and enjoyable lives. In response to Shin’ichi’s remark that the “important thing is fulfillment for oneself and others,” Dr. Galbraith said he would like to foster more dialogue, benefit and joy in the world. And, as if entrusting Shin’ichi with his wish for peace, he urged him to continue his meaningful dialogues toward that end.

Dr. Galbraith also said he hoped they could continue their discussions about peace and the future of humanity and leave a record for posterity. Shin’ichi felt likewise.

Starting from August 2003, a quarter century after their first meeting, their dialogue was serialized in nine installments in the Soka Gakkai–affiliated monthly magazine Ushio (Tide). In September 2005, it was published in book form in Japanese as Dialogue for a Greater Century of Humanism (tentative English title).

In his preface, Dr. Galbraith wrote, “I have great respect for President Yamamoto’s valuable work to promote the welfare of all people wherever they may be.”

In his own preface, Shin’ichi said: “My friendship with Dr. Galbraith is a priceless treasure in my life. I cannot begin to quantify the inspiration his profound and wise words have given me.”

Dialogue connects people’s wishes for peace, forming waves and ultimately a new tide of thought that will transform the age.

Installment 13

On October 10, after his meeting with Dr. Galbraith, Shin’ichi traveled to Osaka. He was scheduled to attend various activities in Kansai and then head to Shizuoka for a memorial service at the head temple commemorating the 700th anniversary[6] of the Atsuhara Persecution.

On the flight to Osaka, Shin’ichi turned his thoughts to that time.

The Atsuhara Persecution refers to the ongoing oppression of Nichiren Daishonin’s followers in Atsuhara Village in the Fuji Shimokata area of Suruga Province (part of present-day Fuji City in Shizuoka Prefecture), which reached a peak in 1279.

For several years before the persecution began, the Daishonin’s disciple Nikko Shonin had been spreading the Daishonin’s teachings among the priests of Ryusen-ji, a Tendai school temple in Atsuhara, and also among local farmers. At Ryusen-ji, a large temple with many resident priests, Nisshu, Nichiben and others converted one after another. Inspired by the Daishonin’s teachings, they eagerly shared them with fellow priests.

The temple’s deputy chief priest, Hei no Sakon Nyudo Gyochi, wielded power at Ryusen-ji. He exploited his status as a member of the ruling Hojo clan and appropriated the temple’s assets for his own personal use. In exchange for money, he even appointed a known thief as an officiating priest. He committed many deeds unconscionable for a Buddhist priest, including selling fish he had killed by poisoning the temple pond (see “The Ryusen-ji Petition,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 2, p. 822).

In addition, Ryusen-ji disregarded the teachings of T’ien-t’ai (Jpn Tendai) stressing the primacy of the Lotus Sutra and recited the Amida Sutra[7] instead. Its faith was distorted from the very foundations.

Nisshu, Nichiben and others whom Nikko Shonin had taught chanted Nam-myoho-renge-kyo dauntlessly in the spirit of the Daishonin. They also sharply pointed out errors in the Pure Land (Nembutsu) and other teachings and emphasized the correct teachings of the Lotus Sutra.

Seeing the growing momentum and success of these efforts to spread the Lotus Sutra, Gyochi feared it would undermine his position as deputy chief priest. Finally, he resorted to intimidating the priests who had become the Daishonin’s followers.

Gyochi oppressed the Daishonin’s followers to protect his own status, not even attempting to discern which Buddhist teachings were correct. Those drunk on power and authority always fear reform.

Installment 14

Openly hostile, Gyochi issued them an ultimatum: The Lotus Sutra, he said, is untrustworthy. They must sign an oath pledging to immediately cease reading and reciting the Lotus Sutra and instead read the Amida Sutra and recite the Nembutsu, the name of Amida Buddha. Then he would guarantee them a place to live (see “The Ryusen-ji Petition,” WND-2, 826).

Some capitulated and abandoned their practice. Adversity tests the authenticity of one’s faith.

Nisshu and Nichiben did not give in to Gyochi’s demands, however, and thus lost their positions at Ryusen-ji. But they continued to reside in secret on the temple grounds while spreading the Daishonin’s teachings in Atsuhara and other villages.

The villagers trusted and respected them so much that the flame of kosen-rufu spread. In 1278, three brothers named Jinshiro, Yagoro and Yarokuro—all farmers in Atsuhara—began practicing. Soon they became leaders among the farmers who had become the Daishonin’s followers.

In 1279, as the gentle days of spring arrived, the sound of voices chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo in many village homes resounded through the fields of Atsuhara. Bitter at the ever-growing number of Lotus Sutra followers, Gyochi began to persecute the farmers as well.

In April, during a festival at a local shrine, amid the excitement of a horseback archery contest, an attacker wounded a follower of the Daishonin named Shiro. Then in August, another follower, Yashiro, was killed. These were warnings of what would happen if believers continued their faith in the Lotus Sutra.

Gyochi instigated these crimes in collusion with the official in charge of the local Fuji Shimokata administration office. On top of that, Gyochi tried to pin the blame on Nisshu and other followers of the Daishonin. The threat of violence must have struck great fear in the Atsuhara farmers.

In “Many in Body, One in Mind,” the Daishonin mentions the people of Atsuhara and says: “Although Nichiren and his followers are few, because they are different in body, but united in mind, they will definitely accomplish their great mission of widely propagating the Lotus Sutra. Though evils may be numerous, they cannot prevail over a single great truth [or good]” (WND-1, 618).

Unity fosters people of courage. Where there is unity, there is victory.

Installment 15

The farmer-believers in Atsuhara encouraged and supported one another and remained utterly unshaken in their faith.

Gyochi and his cohorts thus devised and carried out another malicious plot to oppress them.

On September 21, 1279, officials from the Shimokata administration office arrested 20 of the farmers, including the three brothers Jinshiro, Yagoro and Yarokuro. The apprehended were accused of rice theft and vandalism. Their accuser was Yatoji, an older brother of the three brothers who opposed their Buddhist practice.

How unbearably painful to be hated and persecuted by one’s own parents, siblings or other relatives. That is why the devil king of the sixth heaven often enters the bodies[8] of close family members, causing them to oppose and attack practitioners. The Ikegami brothers, Munenaka and Munenaga, also faced opposition to their faith from their father, Yasumitsu. In particular, the older brother, Munenaka, was disowned twice.

The official complaint accused Nisshu of leading on horseback an armed mob to break into the private quarters of Ryusen-ji’s chief priest and of stealing rice from the temple’s fields and hiding it in his own lodgings (see WND-2, 825).

Of course, this was a complete fabrication.

The arrested farmers were taken to Kamakura. There, Hei no Saemon-no-jo Yoritsuna interrogated them at his private residence. Yoritsuna was the same official who had persecuted the Daishonin. This time, he colluded with Gyochi. Without even addressing the formal charges, he jumped to threatening the farmers: “Renounce your faith in the Lotus Sutra and embrace the Nembutsu teaching. Then you will be set free and have no more worries. Refuse, and you’ll be severely punished.”

The farmers had been practicing the Daishonin’s teachings for only about a year, but none of them wavered.

The strength of one’s faith is not measured by years but by one’s resolve.

Installment 16

In response to Yoritsuna’s threat, the farmers all chanted loudly, an expression of their resolve to uphold the Law even if it meant giving their lives.

Enraged, Yoritsuna instructed his second son, 13-year-old Iinuma Hogan Sukemune, to shoot hikime arrows at the farmers. These whistling arrows with a blunt tip made of paulownia wood were believed to drive demons out of those they struck. They made a shrill sound as they flew and were used in ritual archery contests and other events. How terrifying for the farmers, and how painful.

Such was the cruel torture the farmers endured.

Finally, on October 15, Yoritsuna had Jinshiro, Yagoro and Yarokuro—the central figures among the farmers—beheaded. But even then, none of the others abandoned their faith. They continued chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo resolutely. No doubt their indomitable faith unnerved Yoritsuna. In the end, there were no further executions, with the remaining 17 farmers being sentenced to banishment.

Nisshu, meanwhile, left Atsuhara and resided for a time in Shimosa Province (present-day northern Chiba Prefecture), but he continued to work alongside Nikko Shonin to propagate the Daishonin’s teachings.

The community of believers had grown to encompass priests such as Nissho[9] and samurai retainers such as Toki Jonin and Shijo Kingo, as well as their wives and other family members.

But to propagate the Law throughout the entire world and make the teaching of universal enlightenment a reality, ordinary people needed to establish unwavering faith so they could overcome all difficulties, just as the Lotus Sutra teaches. Many among the Daishonin’s followers, such as the farmers, couldn’t read or write. Nevertheless, they devoted themselves with pure-hearted faith to spreading the Law at the risk of their lives, not giving in to oppression by tyrannical authorities. In other words, there appeared invincible ordinary people who embraced Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, the heart of the Lotus Sutra, and strove for kosen-rufu alongside the Daishonin.

He writes: “If you are of the same mind as Nichiren, you must be a Bodhisattva of the Earth” (“The True Aspect of All Phenomena,” WND-1, 385).

Not only enabling people to become happy themselves but inspiring them to also work for the happiness of others—this is the essence of the Daishonin’s Buddhism of the people.

Installment 17

The Atsuhara farmers’ behavior and way of life exemplify the ultimate in faith. Faith has nothing to do with education, social status or economic standing. It is the courage and resolve to face great difficulties or persecution on account of spreading the Mystic Law, boldly and without fear. It is being able to regard such adversity as a “crucial moment,” remembering and keeping the mentor’s words deeply in one’s heart and having the conviction to follow through on one’s chosen path. It is also being ready to give one’s life for the sake of the Law unfettered by self-interest. And it is having unshakable belief in the principles of Buddhism, free from doubt or hesitation.

On the other hand, Nichiren Daishonin describes those who abandon their faith as “cowardly, unreasoning, greedy, and doubting,” adding that his “words have no more effect [on them] than pouring water on lacquer ware or slicing through air” (“On Persecutions Befalling the Sage,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 998).

“Unreasoning” here means foolish. Elsewhere, he writes: “Foolish men are likely to forget the promises they have made when the crucial moment comes” (“The Opening of the Eyes,” WND-1, 283). Ultimately, their weakness and foolishness cause them to lose sight of their mentor’s teachings and abandon their resolve rather than remain true to their beliefs.

In “Letter to Misawa,” the Daishonin relates how the devil king of the sixth heaven orders his minions to “possess the minds of his [the votary of the Lotus Sutra’s] disciples, lay supporters, and the people of his land and thus try to persuade or threaten him” (“Letter to Misawa,” WND-1, 894–95). During the Atsuhara Persecution, Sammi-bo discarded his faith, and a number of erstwhile followers—such as Daishin-bo, Ota Chikamasa and Nagasaki Jiro Hyoe-no-jo Tokitsuna—joined forces with those persecuting the Daishonin’s followers. This betrayal illustrates the Daishonin’s point.

The devil king of the sixth heaven seeks to disrupt people’s faith by creating unfathomable events or unexpected situations. That’s why we must always remain vigilant in our efforts for kosen-rufu.

In the end, Sammi-bo died tragically; the others suffered serious loss in accord with the law of cause and effect.

Second Soka Gakkai President Josei Toda wrote in a poem:

As you begin the ascent

of a still

steeper mountain,

continue the journey of kosen-rufu

with firm resolve.

Installment 18

That Jinshiro, Yagoro and Yarokuro died for their beliefs amid the Atsuhara Persecution might seem antithetical to Buddhism’s aim of happiness in life.

Life is incomparably sacred, a precious treasure to be protected. Why, then, did the Daishonin write: “Since death is the same in either case, you should be willing to offer your life for the Lotus Sutra” (“The Dragon Gate,” WND-1, 1003)?

Death awaits us all someday. In the Daishonin’s time, countless died in famines, epidemics and armed conflicts. People also had to face the prospect of losing their lives should the Mongol forces invade Japan.

Life is the greatest treasure; but it is as fleeting as the morning dew. The important thing, then, is how we use our lives. Hence the Daishonin says we should not waste our precious lives on “shallow, worldly matters” (“Letter from Sado,” WND-1, 301), but instead dedicate them to protecting and spreading the great, eternal, unchanging teaching of the Lotus Sutra, the teaching that enables all people to attain enlightenment and find happiness.

This is because by doing so, we can attain the state of absolute and indestructible happiness that is Buddhahood. As the Daishonin writes: “By offering their lives to the Lotus Sutra, they became Buddhas” (“On Namu,” WND-2, 1073).

Life is eternal; it spans the three existences of past, present and future. Even should we face persecution and lay down our lives for Buddhism in this present existence, our path would open to attaining Buddhahood in the future.

Moreover, in “Letter from Sado,” the Daishonin tells us that experiencing great hardships for the sake of Buddhism enables us to expiate in this lifetime the negative karma we have accumulated in past existences (see WND-1, 303).

The resolve to give our lives without hesitation and to selflessly dedicate ourselves to propagating the Law is not some sort of tragic fatalism. It is a state of serene and imperturbable joy.

When the Daishonin was about to be beheaded at Tatsunokuchi, he said to a tearful Shijo Kingo: “What greater joy could there be?” (“The Actions of the Votary of the Lotus Sutra,” WND-1, 767). And while enduring the harsh winter in exile on Sado Island, he wrote: “I cannot hold back my tears when I think of the great persecution confronting me now, or when I think of the joy of attaining Buddhahood in the future” (“The True Aspect of All Phenomena,” WND-1, 386).

When we resolve to devote ourselves to kosen-rufu for as long as we live, we connect on the deepest level with Nichiren Daishonin, the Buddha of the Latter Day of the Law.

A fearless strength emerges, and the joyous life state of a Buddha pulses within.

Installment 19

Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, the Soka Gakkai’s first president, died in prison defending the correct teaching of Nichiren Daishonin. Nichiren Shoshu, in contrast, feared persecution by Japan’s militarist authorities and acquiesced to their demand to enshrine the Shinto talisman. Thus, they betrayed the Daishonin’s spirit. Makiguchi’s selfless dedication to spreading the Law, ultimately laying down his life for Buddhism, is the starting point of the Soka Gakkai spirit.

Makiguchi’s disciple Josei Toda, who later became the second president, was arrested and imprisoned along with his mentor. Toda awakened to his identity as a Bodhisattva of the Earth while incarcerated, and upon his release dedicated his life to kosen-rufu.

The question “What would you die for?” could be rephrased as “What would you live for?” They are two sides of the same coin.

Makiguchi, the mentor, gave his life to protect the Daishonin’s teachings; Toda, the disciple, inherited his mentor’s conviction and devoted his life to realizing the cause of kosen-rufu. Both men embodied the sublime spirit and practice of selflessly dedicating their lives to propagating the Law.

The Soka Gakkai now flew smoothly like a large jet plane. But Shin’ichi Yamamoto had prepared himself for any severe turbulence on the journey of kosen-rufu like in the days of the Atsuhara farmers and President Makiguchi. As president, he put his all into piloting the Soka Gakkai, vowing to never allow a situation that would cause members to be sacrificed. And if a life-threatening persecution should arise, he was determined to take it on alone.

Of course, to advance kosen-rufu, we each need to be ready to devote our lives selflessly to spreading the Law. Only with such firm resolve can we attain Buddhahood in this lifetime and transform our karma.

To be ready to do this means deciding that life’s ultimate purpose is kosen-rufu. It means demonstrating the power of the Gohonzon and the truth of Nichiren Buddhism in our lives and way of living, not for fame or personal gain but to share the teachings with others.

We carry out Soka Gakkai activities and pray earnestly that, for the sake of kosen-rufu, we can become healthy, transform our financial difficulties, build a harmonious family and so on. Prayers based on a vow for kosen-rufu are the prayers of the Buddha and the Bodhisattvas of the Earth; therefore, they activate the protective functions of the universe.

Installment 20

We strive in our faith and practice so we can “enjoy ourselves at ease” (see The Lotus Sutra and Its Opening and Closing Sutras, p. 272)—in other words, to enjoy a serene and unhindered state of happiness.

People often think that gaining wealth and fame will automatically bring happiness. But if we look for happiness outside ourselves, pulled this way and that by our desires, we’ll never know true fulfillment and satisfaction. Though we may get what we want, our joy will be short-lived. Soon we’ll feel empty again. Human desires have a way of growing and expanding, and if we can’t get what we want the next time, we’ll become dissatisfied and anxious.

Such is the limited pleasure gained from fulfilling worldly desires. On the other hand, “boundless joy of the Law” describes the supreme and absolute happiness of attaining enlightenment. This happiness does not come from the outside but wells up from the depths of our being.

That is why Nichiren Daishonin declares: “There is no true happiness for human beings other than chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo” (“Happiness in This World,” WND-1, 681). The “boundless joy of the Law”—true happiness—is found in chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. More importantly, true happiness is found in practicing for both ourselves and others. As the Daishonin says: “You must not only persevere yourself; you must also teach others. …Teach others [about Buddhism] to the best of your ability, even if it is only a single sentence or phrase” (“The True Aspect of All Phenomena,” WND-1, 386).

Those who take action for kosen-rufu are Bodhisattvas of the Earth. The Daishonin tells us that these bodhisattvas possess the four noble virtues of the Buddha—eternity, happiness, true self and purity.

“Eternity” means that the state of Buddhahood inherent within Buddhas and all living beings abides eternally throughout the three existences—past, present and future. “Happiness” is a state of tranquility free from suffering. “True self” means that Buddhahood is our true and intrinsic nature, an independent, indestructible strength. “Purity” means that no matter how corrupt and polluted the age, our lives function purely, like a clear, flowing spring. By establishing a life state imbued with eternity, happiness, true self and purity—a state born from our resolve and efforts to selflessly spread the Mystic Law—we can genuinely “enjoy ourselves at ease.”

Installment 21

Shin’ichi reflected on how the Soka Gakkai’s development and the kosen-

rufu movement’s dynamic postwar growth came about solely because second Soka Gakkai President Josei Toda and the members carried on the spirit of selfless dedication to spreading the Law embodied by the Soka Gakkai’s first president Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, who withstood persecution and died in prison for his beliefs. Shin’ichi pondered the Daishonin’s words “If the spring is inexhaustible, the stream will never run dry” (“Flowering and Bearing Grain,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 909).

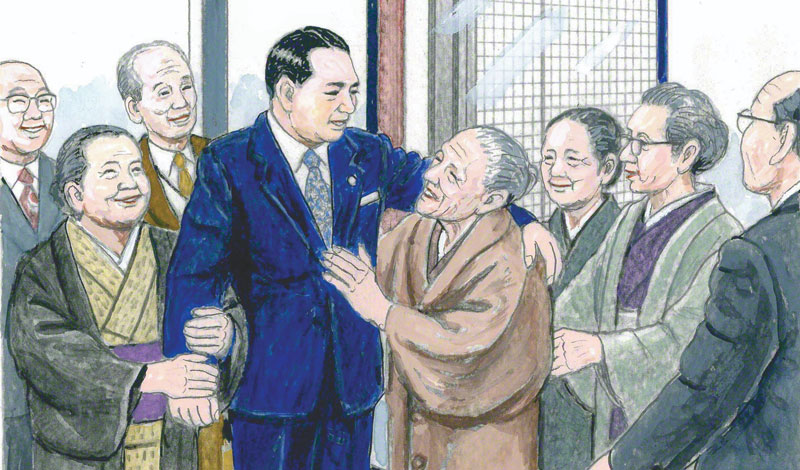

On the evening of October 11, Shin’ichi attended a general meeting of Osaka’s Joto Ward at the Kansai Toda Memorial Auditorium in Toyonaka City commemorating the 700th anniversary of the Atsuhara Persecution.

Speaking of that history, he discussed the contemporary meaning of giving one’s life for Buddhism.

“Today, with our kosen-rufu movement steadily growing into a mighty river, it is important that all of you lead long and happy lives, without anyone being sacrificed or left behind. That is my heartfelt prayer and wish.

“To continue vigorously chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo with great conviction in faith, no matter what; to teach others about Buddhism and encourage them; and to live out our lives fully for the sake of kosen-rufu, showing actual proof of our own happiness—please know that this is what it means for us to give our lives for Buddhism in this day and age.”

To give one’s life for the Law is not, by nature, an act of heroism that glorifies death. It is deciding that kosen-rufu is the purpose of our lives and, while grappling each day with the realities of society, persevering in faith and becoming champions of happiness. This is the great path of practitioners of Nichiren Buddhism in modern times.

Shin’ichi continued his guidance tour in Osaka and Kyoto, and then traveled to Shizuoka, where he participated in a memorial service commemorating the Atsuhara Persecution’s 700th anniversary.

On October 14, an “Evening Commemorating the Atsuhara Persecution” was held at the Tonohara Athletic Field [on the head temple grounds], where members performed an original dance called “The Three Martyrs of Atsuhara.”

The vibrant dance brimmed with their passion to live with the same unwavering faith as the three Atsuhara martyrs. They had all practiced diligently, finding time while working hard at their jobs and engaging in their Soka Gakkai activities.

Shin’ichi applauded the performance, calling out in his heart: “The noble spirit of the three martyrs is alive in the Soka Gakkai. As long as the Soka Gakkai exists, the correct teaching of Nichiren Buddhism will not perish!”

Installment 22

That month’s headquarters leaders meeting was held at the Itabashi Culture Center in Tokyo on the afternoon of October 21.

During his speech there, Shin’ichi talked about his motivation in writing Soka Gakkai songs.

“I’ve written several songs this year at the requests of various regions and prefectures and also divisions. Our members strive tirelessly in their Soka Gakkai activities each day. I wanted to convey my heartfelt thanks and appreciation to each one of them.

“Clumsy though my efforts may be, I have done my very best, wishing to bring our members joy and, at the very least, some encouragement and hope.

“Most recently, the women’s division and Ibaraki Prefecture leaders have made requests, so I have written a new song for the women’s division called ‘Song of Mothers’ and one for Ibaraki, ‘A Life of Victory.’ I’d like to introduce the lyrics to you today.”

First was “Song of Mothers.”

Child in arm, sweat on her brow,

she strives day after day—a brilliant sight—

to fulfill her noble mission from the distant past.

Who will praise this mother?

Protecting her humble castle,

she is a tiny sun, ever constant,

bringing light to one and all,

this future great mother of happiness.

Ah, overcoming life’s sorrows,

the mother’s sincere prayers

reach beyond the hills of despair

to where her castle is filled with smiling faces.

Gentle and strong is the mother,

a white lily blooming in her heart,

age meaning nothing to her.

Heavenly deities, watch over her dance!

Glorious music, the song of mothers.

Installment 23

The women in the audience broke into cheers and applause that went on for some time.

When it finally died down, Shin’ichi said: “The song expresses my heartfelt admiration for the women’s division’s tireless efforts.”

Applause erupted again.

Shin’ichi had written the lyrics just the evening before. Earlier that day, he had met with women’s division region leaders at the Soka Women’s Center (later, the Shinano Culture Center).

One after another, they reported on activities in their local organizations. They told Shin’ichi of the members receiving incredible benefits and how the women’s division strove to encourage fellow members amid Nichiren Shoshu priests’ repeated outrageous attacks. They also stated their wish for a new women’s division song.

The women’s division had decided to create a new song to mark the opening of the Soka Women’s Center in June, and volunteers had produced a tentative draft titled “Castle of Mothers.”

After he read it, Shin’ichi shared his thoughts: “The song refers to the Soka Women’s Center as the ‘castle of mothers,’ but I think it would be better not to limit that expression to one building.

“We have millions of women’s division members. But as far as I know, only about 60,000 have visited the new center, so calling it the ‘castle of mothers’ will not have much meaning for the majority who have never been there.

“I think it should be your home that is regarded as the ‘castle of mothers.’ Nichiren Daishonin says: ‘The place where the person upholds and honors the Lotus Sutra is the “place of practice” to which the person proceeds’ (The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings, p. 192).

“In other words, the true teaching of Buddhism is that the place where we carry out our Buddhist practice each day is the training ground for attaining enlightenment. We each build indestructible happiness where we are and transform our home into the Land of Tranquil Light. As women’s division members, each of you has the mission to make your home a castle of happiness, a castle of mothers.”

Our homes are the starting point for creating happiness.

Installment 24

Shin’ichi initially began the song’s second verse with “Protecting her humble home.” But then he decided to change “home” to “castle,” thinking it a better way to convey that a mother’s home is in fact her castle.

He also used “tiny sun” to describe the women’s division—the mothers of kosen-rufu. Come rain or shine, the sun rises each day without fail. Whatever happens, it does what it must, persistently fulfilling its mission and illuminating all with its warm light.

Great achievements are made through painstaking, persevering efforts.

He started on the third verse. “Ah, overcoming life’s sorrows…”

Here, he depicted life’s struggle against cruel destiny.

Life has its raging storms; it is never entirely smooth sailing. Though others may be unaware, most people grapple with some kind of serious problems, sometimes enduring painful situations. Waves of suffering come crashing in one after another.

That’s why we chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo! That’s why we share Nichiren Buddhism with others!

Awakening within us the great life force of the Bodhisattvas of the Earth and the Buddha, we confidently triumph over every obstacle with strong, open and rich hearts.

It is by overcoming our karma and our problems that we can prove the benefit, validity and greatness of Nichiren Buddhism. We transform our karma into our mission. There is nothing we can’t resolve through our Buddhist practice.

Sometimes icy rain pounds us and clouds of despair shroud our hearts. But always remember that the sun will rise to shine again, today and tomorrow.

By aligning our lives with the Mystic Law, which permeates the entire universe, we ourselves come to shine like the sun. We radiate the joy of victory and brilliant achievement, and illuminate our family, our community and the future with the light of happiness.

Shin’ichi infused the women’s division song lyrics with this hope and heartfelt cry of encouragement.

Installment 25

When Shin’ichi reached the last line of the third verse, he said to Mineko: “Here, I’d like to mention their partners. In the men’s division song ‘Life’s Journey,’ I put the line ‘Ah, untold mountains and rivers crossed with partners and family’; I’d like to do something similar here.”

“Yes, but some women’s division members have lost their partners and work hard alone to raise their children. In addition, some are single.”

“I see your point. All right, let’s go with ‘her castle is filled with smiling faces’ to embrace all situations, including partners.”

Shin’ichi then moved on to the fourth verse.

“Mr. Toda likened the women’s division to white lilies, so I’d like to use that here. How about ‘Gentle and strong is the mother, / a white lily rising in her heart’? White lilies symbolize the Soka Gakkai women’s division. I want them to always be proud of that.

“What do you think? It’s a song for the women’s division, so I’d like your honest opinion.”

Mineko smiled and said: “Since you’re using the metaphor of white lilies, I think ‘blooming’ works better than ‘rising.’”

“OK, let’s go with that. And since women’s division members range from newlywed 18-year-olds to those in their advanced years, I’d also like to mention our elderly members who’ve worked so hard since the pioneering days. So many continue even in old age to energetically support, protect and encourage their juniors.”

Shin’ichi thus concluded the last verse with “age meaning nothing to her. / Heavenly deities, watch over her dance! / Glorious music, the song of mothers.”

It took him less than 10 minutes to dictate all four verses.

He looked over the lyrics on a clean copy Mineko made, but there was no need to change anything. He named it “Song of Mothers,” based on the song’s closing line.

References

- Chang-an (561–632), a disciple of the Great Teacher T’ien-t’ai. These words appear in the commentary accompanying The Profound Meaning of the Lotus Sutra, lectures of T’ien-t’ai that Chang-an recorded and compiled. ↩︎

- Lev Tolstoy, “Karma,” accessed September 19, 2024, https://archive.org/details/Karma_LevTolstoy/page/n1/mode/2up. ↩︎

- John Kenneth Galbraith, Ambassador’s Journal: A Personal Account of the Kennedy Years (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1969), p. xx. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- See “The ‘Entrustment’ and Other Chapters,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, pp. 914–15. ↩︎

- According to the traditional Japanese way of counting. ↩︎

- Amida Sutra: One of the three main Pure Land scriptures. ↩︎

- This is a metaphor for negative functions arising from fundamental ignorance taking control people’s hearts and minds. ↩︎

- Nissho (1221–1323): One of the six senior priests designated by Nichiren Daishonin. He was Nichiren Daishonin’s first convert among the priesthood. ↩︎

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles