Living Buddhism: Ron, thank you for speaking with us today. You’re a native of Philly, born and raised. Tell us how you first heard of Nichiren Buddhism 52 years ago.

Ronald Williams: Hardly remember, to tell the truth. Not because I was high—I was—but because I was unimpressed by the person who told me—a friend who always managed to have the best weed in town. We were at his place when he told me about Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. Told me he’d only just begun and then fired off a list of his personal benefits he’d had so far. It’s not that I wasn’t interested in material things—I was—but I hadn’t come to him for those. I’d come for weed. I’d come to get high and I left high, but also, somehow, with a copy of a Seikyo Times—predecessor of Living Buddhism—under my arm. I tossed it in the back seat and forgot about it. It wasn’t until one week later, washing my car, that I saw it there in the back seat and, thinking to skim a sentence or two, opened it up. Before I knew it, I was sitting in the back seat, reading page after page.

I remember there being an essay by Daisaku Ikeda, who I understood was the president of this Buddhist movement. It was about relationships—creating harmonious relationships, which was not something I’d given much thought to. I thought over my own relationships, none of which I could describe as harmonious. My parents were worried, my grandparents, too, about the path I was on and the company I kept. For good reason—my friends were all after money, drugs, parties and booze. The same worry drove my first wife up the wall. She watched at her wits end as I spent my paychecks—peanuts to begin with—on short-term pleasures that got us nowhere and benefited no one. Sitting there, I thought about these things. Under my breath, squinting at the unfamiliar print, I tried to sound it out:

Nam-myoho-renge-kyo.

That’s quite a lofty concern that sparked your practice—harmonious relationships.

Ronald: It is what got me chanting. But frankly, my mind quickly turned back to its original concerns—money. Which was a pressing issue.

My wife and I had just moved to the north side of Philadelphia, renting a small home on its outskirts. I can’t remember which expense took me down to my last dollar, but I do remember the amount—$20. I was $20 short and needed to not be by day’s end—highly unlikely given we were a week out from payday. That morning, I chanted Nam-myoho-renge-kyo the whole drive into work where, upon arrival, I got my assignment: to drop off auto parts.

“Truck’s International,” my boss told me, and nodded in a kind of northerly direction. He seemed to think I knew my way around, and being new and young and anxious, I didn’t want to disappoint. So I set off with what I’d been given—just a name and a nod at the woods—back in the direction I’d come.

I hit the road a little before noon. Passing by my house, I made a pitstop for a sandwich, checking my mailbox on my way in. In one letter, I found a check made out for $70. Confused, I read the attached explanation: I was being refunded for some faulty charge two years earlier. Impressed, I hit the road again and headed north, chanting with renewed vigor.

I reached the woods and got quickly turned around. Hoping to make it to the woods’ edge to get my bearings, I turned down a little dirt road that, I realized too late, was a one-way deal—I’d have to take it to the end, wherever that happened to be. The whole time, I chanted.

At some point, the woods broke open in a patch of sky, where a lone traffic light hung. Beneath it was a gas station, and I thought, Maybe someone here knows where I’m going. So I pulled in and got out of the car and what do you know? I’m looking at Trucks International. Right there across the street. I checked my watch and found I was on time, and I thought to myself, This chanting really works.

It was enough to get you interested.

Ronald: It was. I got connected to a district and stayed connected. The reason being the community and its message, which told of the power of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo—the power people had within themselves to change their own lives and destiny for the better. I saw it firsthand from the jump—the joy these people felt in experiencing the actual proof and benefit of the practice. I remember the first monthly contribution I ever did—I did it right off the bat. I gave what I could, which happened to be $20. And once I started, I never stopped.

As my faith grew, so did my desire to financially protect the kosen-rufu movement. I continued to make sustaining contributions, once a month, to offer steady support to the community and the movement I saw and felt was truly helping people transform their lives. Over the years, as my faith, understanding and appreciation grew, so did my contributions. Increasing my Sustaining Contribution amount has been a tangible way to express deep gratitude for all that I’ve gained through my Buddhist practice.

Tell us about the community and its impact on your life.

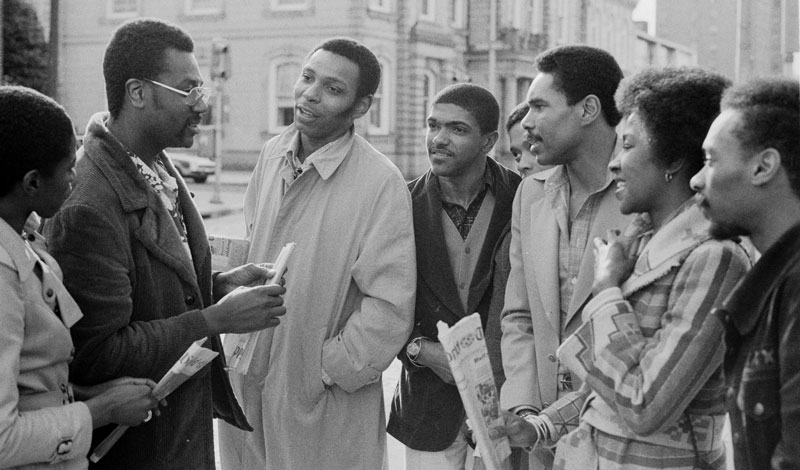

Ronald: It was certainly a different kind of company than the kind I’d kept ’til then. Connected with these bright, dedicated people, I naturally peeled away from the pleasure seekers and the substances. Crucially, I became a member of the Traffic Control Group (TCG)—predecessor of today’s Soka Group—a training ground for the young men’s division. In this group, I learned how to live and how to lead. I learned how to take and give feedback while putting others at ease. I learned how to unite in prayer around a cause—namely, the safety and well-being of others. Perhaps most important, I learned the power of consistent action for others—that consistent action for the sake of something greater than myself was the surest, shortest path to enormous growth.

How did you know you were growing?

Ronald: People told me, for one. For instance, my wife at the time, she teased me about the chanting at first. In the evenings I’d hear her and her friends giggling at what must have seemed off the wall—me, of all people, upstairs chanting this chant. I was consistent though—morning and evening—and within a couple months, my wife was right there beside me, having recognized big, undeniable changes in me. One by one, her friends followed suit, seeing how much brighter the two of us had become. To this day, a number of those friends are frontline leaders of our movement.

They weren’t the only ones to see a difference. Consistently praying and taking action to support and contribute to others is at the heart of Ikeda Sensei’s behind-the-scenes training groups for young people. Everything I was learning in the TCG, I carried into my daily life—as a father, husband, friend and employee. Naturally, family, friends and colleagues took note. At work, as at home, an extraordinary thing was taking place: I was beginning to be perceived as a person of strength and conviction.

An early result of this came in 1973, one year out from receiving the Gohonzon. At the young age of 25, my colleagues nominated me to represent them in the union. I accepted and was voted into the role.

That is young. What did that entail?

Ronald: Many heart-to-hearts. As a union leader, I had endless opportunities to speak with young men—some my age, some a little older—many of whom reminded me of myself, of the person I was before encountering Buddhism. They trusted me, knowing that I would go to bat for them, for their rights. And I was able to convey to them that to represent them effectively, I needed them to show up fully. Common issues ranged from attendance to punctuality, from performance to a careless remark. Chanting each day for the happiness of my colleagues, to create a harmonious Buddha land at my place of work, I sat down with many young people over the years to listen and move forward together. It’s my understanding that my message was not always an easy one to hear. But they understood that I was in their corner—I wanted them to win and would fight for them to win. I have no doubt that they registered, somewhere in their lives, my prayer for them and responded to that.

Every five years, for the rest of my working life, my colleagues voted me into this same role, trusting me to represent them fairly and courageously.

You worked for the city for 38 years. What was your greatest challenge?

Ronald: I was injured on the job in ’81 and sidelined for about a month, assigned to “light duty,” which is to say, paperwork. Within a month I was healed and ready to return to the hands-on work I loved. When I let this be known, however, my boss surprised me by asking me to stay on in administration. He needed a good administrator, he admitted, and apparently, I qualified. Having borne the brunt of the paperwork for a month, I had to agree that one was needed. Reluctantly, I accepted, chanting to be of the most help to my boss and colleagues.

How long did you do administration?

Ronald: Over three years.

Three years?

Ronald: And each year was more difficult than the one before. It wasn’t the work—the more familiar I became, the easier it was. No, what made it difficult was the promotions. As the years rolled by, we acquired new hires, young automotive technicians who were quickly promoted into hands-on roles I would have loved to do, roles that, given my decades of expertise, should by rights have been offered to me. To rub salt in the wound, no one was being hired on to do the work they were promoted out of. As each was hired into a specialized role, their administrative work was left to me. And to top it off, this was 1981, the same year as my divorce. If there were ever a time in my life that I might have grown bitter, it was those three years: 1981–84.

How did you respond?

Ronald: With continued prayer and action. I was a chapter men’s leader, which meant I had people to visit, to encourage and support. This was my saving grace. I’d visit the members, hear their struggles and, where appropriate, share my own. We’d get in front of the Gohonzon, chant powerful daimoku, study Nichiren Daishonin’s writings and Ikeda Sensei’s encouragement, and move forward with conviction together.

With regards to work, I continued to pray to show actual proof. I prayed for the happiness of my boss and the great success of the young men he was so swiftly hiring and promoting. I began to look at the extra work—a truly staggering amount of overtime—as an opportunity to support the youth entering the field. As the work grew, so did my prayer for their happiness. In short, I continued to do what I’d always done—support those around me to the best of my ability.

And then?

Ronald: Well, more than three years of automotive administration had made me something of an expert. But by 1984, I was finally able to return to the work I loved.

I was 35 at the time and wouldn’t find out for another 15 years the kind of fortune I’d built for my life during those difficult years.

Nearing retirement, I inquired about my situation—about my pension and all that—and discovered to my astonishment that at the young age of 59, retiring was the most lucrative thing I could do—more lucrative than continuing to work. My pension, based on my three consecutive years of highest paid work, surpassed my income. There’s not a doubt in my mind which three years these were.

In any case, I feel I owe it all to my consistent contributions and efforts to respond to Sensei—supporting and protecting the SGI to the best of my ability.

In this country, 59 is indeed young to retire. What would you say have been your top concerns in your third stage of life?

Ronald: Well, finances, I’d say, are the least among them. I’m not rich, but I have a healthy financial situation that allows me to focus on other things—on my health for instance—I’m more healthy now than I’ve ever been. I can focus on relationships with my kids, my friends and my family. I wouldn’t say these are my “top concerns” though. I’m just so appreciative for everything in my life. These days, I’m enjoying a lot of senior activities. With the friends I make, I share with them the joy of my Buddhist practice and a vision—my mentor’s vision—of a world at peace with itself.

Beautiful. You mentioned your kids? You’ve got three, is that right?

Ronald: That’s right—two daughters and a son. All of them practicing Buddhists.

That’s quite something, isn’t it, that all three practice this Buddhism. Why do you think that is?

Ronald: All right. This is not to toot my own horn, but they’ve seen me at it for 52 years. I’ve been consistent. And they know that much about me—that I’m consistent and will be there for them when it matters, that’s all.

How do you know how they feel?

Ronald: Well, they tell me, now and again. For instance, I got a letter from one of my daughters on Father’s Day, which was just about the best kind of letter a father could get. I’m not one to keep sentimental things around the house, but I’ve kept that right here on my desk. It reminds me of the person I’ve become. A person of conviction. It reminds of where my conviction has come from—from consistently supporting others.

If it’s all right, would you read it for us?

Ronald: Well, sure, I have it right here. It goes:

For all the times you told me I could do it, that you believed in me and that I made you proud; for all the ways you showed me I was important, that my opinion mattered and that I could always depend on you; for all the things you gave me, like principles, confidence and unconditional love, I want to say thank you and I love you. It takes a very special man to be a loving father.

And then it goes on a bit…

What does it say?

Ronald: You mean at the end there?

Yes.

Ronald: All right, it says—she says: You are truly a great man.

Whatever I am, I’ve become by steadily supporting and contributing to others.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles