Bob Parsons was in the U.S. Marines when deployed to Da Nang, South Vietnam, to command a platoon of men barely old enough to vote.

It was here that he decided that his responsibility lay not in creating dead heroes but living ones. He chanted Nam-myoho-renge-kyo fervently each day to make that happen; and, against every conceivable odd, his entire platoon returned home intact.

His experience, of course, was the heartbreaking exception. More than 58,000 U.S. servicemembers lost their lives, with another 153,000 wounded. That is to say nothing of the untold survivors who experienced severe psychological damage and lasting health effects.

This month, we mark 50 years since U.S. troops withdrew from Vietnam on March 29, 1973, ending nearly a decade of direct combat between the U.S. and North Vietnam. The war did not end until two years later, with over 3 millions deaths.

The anguish of war is captured in the opening lines of The Human Revolution, where Ikeda Sensei writes: “Nothing is more barbarous than war. Nothing is more cruel.”[1]

Buddhism describes violence and war as a devil, or mara in Sanskrit, which means murderer or robber of life. In discussing the Vietnam War, Sensei explains how this function manifests in our lives and how we as Buddhists can combat it:

According to Buddhism, the devil king of the sixth heaven is the epitome of this negative, destructive force. The true nature of this devil king, who is said to dwell in the Heaven of Freely Enjoying Things Conjured by Others, is the desire to enslave others and to manipulate them for their own advantage. … When it gains control over people’s hearts, they are led to engage in murderous and destructive behavior and to start wars. What, then, can defeat the devil king of the sixth heaven? Only one thing: the life state of Buddhahood.[2]

The way we, as SGI members, confront this devilish nature is by awakening the Buddhahood in increasing numbers of people, teaching them the core philosophy of Buddhist practice, human revolution, which enables anyone to establish peace in their hearts.

In his September 1991 address at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, Sensei shares an episode from the life of Shakyamuni to underscore that peace is possible.

Shakyamuni was once asked the following question: “We are told that life is precious. And yet all people live by killing and eating other living beings. Which living beings may we kill and which living beings must we not kill?” To this simple expression of doubt, Shakyamuni replied, “It is enough to kill the will to kill.”

Shakyamuni’s response is neither evasion nor deception but is based on the concept of dependent origination. He is saying that, in seeking the kind of harmonious relationship expressed by respect for the sanctity of life, we must not limit ourselves to the phenomenal level where hostility and conflict (in this case, which living beings it is acceptable to kill and which not) undeniably exist. We must seek harmony on a deeper level—a level where it is truly possible to “kill the will to kill.”[3]

In this issue, we hear from three Vietnam veterans who, having advanced kosen-rufu for decades in their communities, believe that the SGI’s movement of human revolution is indeed the key to peace. It’s a vision they’ve upheld by sharing the same vow and spirit as their mentor, expressed in the opening lines of The New Human Revolution, where Sensei writes: “Nothing is more precious than peace. Nothing brings more happiness. Peace is the most basic starting point for the advancement of humankind.”[4]

My SGI Activities Create a Better World for Future Generations

by Tony Goodlette

Falls Church, Virginia

When I was a child, my father gave me to an orphanage. I grew up angry and saw no meaning to life.

I was in Vietnam from 1967 to 1975. There, I saw things that caused unbelievable psychological stress. One was Operation Babylift, where we tried to evacuate Vietnamese orphans. One of the flights crashed, killing most of the children. After Vietnam, I dulled my memories with alcohol.

In 1981, I was introduced to Nichiren Buddhism and joined the SGI. The teachings of Nichiren and Ikeda Sensei opened my eyes to the preciousness of life, including my own.

Another challenge I faced, however, was being exposed to Agent Orange, a chemical the U.S. government used to defoliate the land where the Viet Cong could be hiding. Over the years, I developed Type 2 diabetes, a brain tumor and congestive heart failure, as well as hearing loss. But my Buddhist practice put me in rhythm with my environment, enabling me to receive excellent medical treatment for these issues.

The nature of war takes away the essence of life. No matter how many movies you make, you can’t capture the profound suffering manufactured by war.

In the SGI, we collaborate to produce happiness and elevate human dignity. In addition to eradicating war, we need to resolve the disasters resulting from climate change that have begun. I engage in my SGI activities confident I’m creating a better world for future generations as my focus.

At 78, I am fully enjoying my life, with my children, grandchildren and now great-grandchildren! I chant each day to meet young people and continue the battle for kosen-rufu with Sensei.

My Experiences in War Taught Me That the District Is the Key to Peace

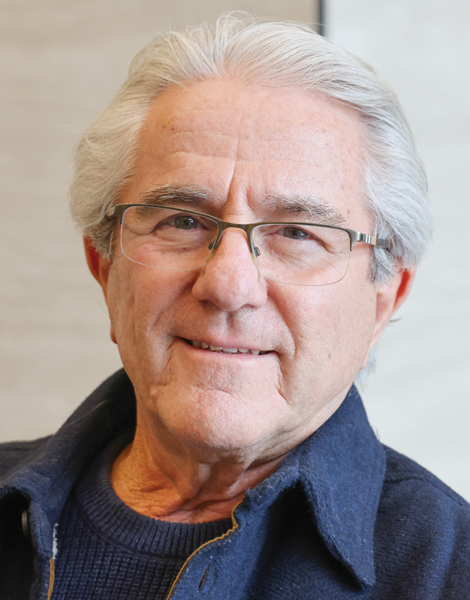

by Bob Parsons

Marana, Arizona

I was a one-year SGI member when I got orders to deploy to Vietnam. At 22, I was put in charge of a platoon of around 60 U.S. Marines, most of whom were still teenagers. I chanted Nam-myoho-renge-kyo late at night for my platoon to be protected. I developed a proximity awareness, where I sensed danger, enabling us to skirt imminent death. I feel as if my daimoku created a dome of protection for me and my men; and we all came out alive. I was deeply moved when, 30 years later, Ikeda Sensei wrote about my experience in The New Human Revolution.[5]

I was with Sensei in Hawaii in July 1985, when he visited the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. He wrote in the guestbook that he was praying for the peaceful repose of all the fallen in the Pacific War. In that moment, I saw him as a global citizen who didn’t favor one nation but put the happiness of humanity above all else.

My military career lasted 15 years, which caused post-traumatic stress disorder that forced me to bounce around careers. I walked around half-pissed-off much of the time, unable to take instructions. Through Buddhist practice and treatment, I transformed my trauma.

After all my experiences, I have no doubt that each SGI district is the key to creating peace. My district—despite being located on the outskirts of Tucson, Arizona, where the residents are primarily older, politically conservative folks— has seven nationalities represented. We all come together to inspire one another to go into the community and spread the roots of peace and understanding into more hearts, and break down the superficial barriers that can all too easily escalate into war.

Empowering One Person Creates Waves of Happiness

by Eric Bruck

Los Angeles

On my 23rd birthday, I woke up in barracks and was inducted into the U.S. Army. I had joined the SGI just a few months earlier, which enabled me to rekindle my sense of purpose.

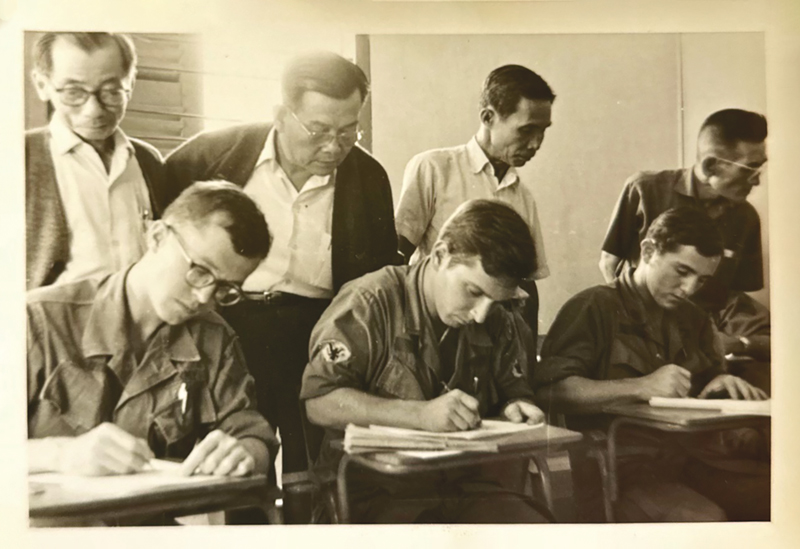

With the Gohonzon, SGI publications and Ikeda Sensei’s The Human Revolution in hand, I resolved to bring the fight for kosen-rufu with me to the war zone. I introduced a number of fellow GIs to Buddhism, two of whom I brought to Japan to receive the Gohonzon!

My Buddhist practice put me in rhythm with the Mystic Law, protecting me from deadly situations. In one instance, one of the cooks in our barracks began shooting up our camp, killing a medic. When I returned to my room, there were bullet holes that would have struck me had I been there.

During my deployment to Vietnam, I began a newsletter with two other members that we called The Gakkai Grunt, a grunt being slang for a GI. I felt the power of words were the best way to combat the urge for violence. We reprinted articles from SGI publications and added experiences of soldiers. After gathering contact information for deployed members, I sent the newsletter to some 60 U.S. personnel in Vietnam each week.

Another experience solidified my commitment to peace. One day, when I accompanied a doctor to a hospital ship, we entered a massive morgue, lined end to end with body bags. We opened up one to find a young man in his early 20s with his torso blown off. I looked at his nametag and immediately thought of his parents and friends, his hopes and opportunities, all robbed by this war. I thought about the ripples of suffering from the senseless death of one person. I now think about how endless waves of happiness are created by empowering just one person to transform their karma with the Mystic Law.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles