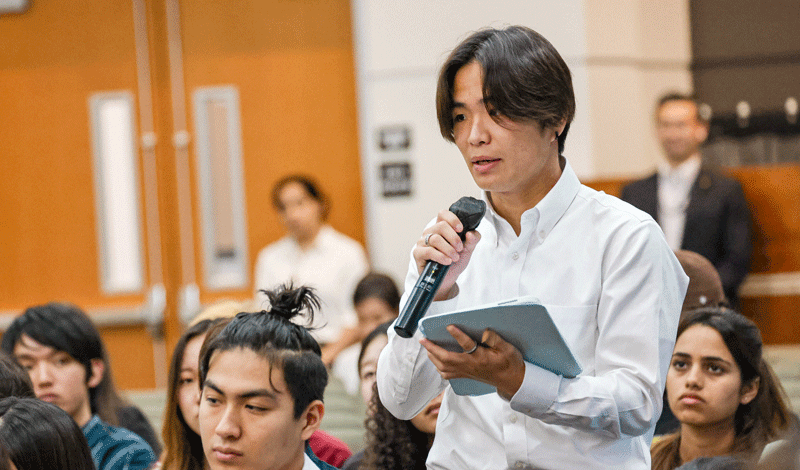

SGI Vice President Yoshiki Tanigawa presented the following lecture on global citizenship at a student division meeting held in Laguna Hills, Calif., on May 24, 2023.

by Yoshiki Tanigawa

SGI Vice President

On June 13, 1996, Ikeda Sensei gave a lecture titled “Thoughts on Global Citizenship” at Columbia University’s Teachers College. This was just a few years before the start of the 21st century, which Sensei envisioned as a Century of Life. Throughout the 1990s, he gave key addresses at various academic institutions, starting with his 1991 Harvard University address, through which he strove to convey that it is possible for humankind to transform its destiny. And in this Columbia University address, Sensei seems to offer his conclusion. In the question-and-answer session that followed, he also mentions his idea to create Soka University of America.

In his series of lectures in the 1990s, Sensei discusses the crises facing modern Western civilization’s values, world views and perspectives on nature and the environment. And he offers the following:

No person or thing exists in isolation. Each individual being functions to create the environment that sustains all other existences.

All things are mutually supporting and interrelated, forming a living cosmos, what modern philosophy might term a semantic whole. That is the conceptual framework through which Mahayana Buddhism views the natural universe. (My Dear Friends in America, third edition, p. 345)

• • •

The Buddhist principle of dependent origination reflects a cosmology in which all human and natural phenomena come into existence within a matrix of interrelatedness. Thus, we are urged to respect the uniqueness of each existence, which supports and nourishes all within the larger, living whole.

(MDFA, 366)

Based on this point, Sensei proposes that we can overcome the crises facing humanity by changing how we view life and death, self and other, and people and nature. He states:

Buddhism regards life and its environment as two integral aspects of the same entity. The subjective world of the self and the objective world of its environment are not in opposition nor are they a duality. Instead, their relationship is characterized by inseparability and indivisibility. (MDFA, 130)

Sensei also explains:

We are beginning to understand that death is more than the absence of life; that death, together with active life, is necessary for the formation of a larger, more essential, whole. … A central challenge for the coming century will be to establish a culture based on an understanding of the relationship of life and death and of life’s essential eternity. Such an attitude does not disown death but directly confronts and correctly positions it within the larger context of life. (MDFA, 338)

Moreover, he expresses a view of life and death in which one can find joy in both life and in death.

Toward this end, he emphasizes what is needed:

We must promote the kind of grassroots education that will foster world citizens committed to the shared welfare of humanity, and we must foster solidarity among them. (MDFA, 368)

And he says this comes down to “the process of human revolution, the reformation of the inner life, its expansion toward and merger with the greater self of wisdom, compassion and courage” (MDFA, 370).

In order to overcome the various issues facing humanity on a global scale, the only resolution is to nurture global citizens who can inherit this perspective and create value on a planetary level. Sensei has clearly explained the necessary qualities of such global citizens:

• The wisdom to perceive the interconnectedness of all life and living.

• The courage not to fear or deny difference, but to respect and strive to understand people of different cultures and to grow from encounters with them.

• The compassion to maintain an imaginative empathy that reaches beyond one’s immediate surroundings and extends to those suffering in distant places. (MDFA, 444)

These three essential elements of global citizens have also become the founding principles of SUA.

There are two indispensable points for understanding his address that I’d like to confirm today.

First, he explains that the bodhisattva, described in Buddhism, is a fitting model for global citizenship:

The practice of the bodhisattva is supported by a profound faith in the inherent goodness of people. …

For this reason, the insight to perceive the evil that causes destruction and divisiveness—and that is equally part of human nature—is also necessary. The bodhisattva’s practice is an unshrinking confrontation with what Buddhism calls the fundamental darkness of life. (MDFA, 446)

What does it mean practically to engage in this unshrinking confrontation with fundamental darkness? Nichiren says, “The single word ‘belief ’ is the sharp sword with which one confronts and overcomes fundamental darkness or ignorance” (The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings, pp. 119–20). There is no other way to battle this fundamental ignorance other than carrying out Buddhist faith, practice and study focused on advancing kosen-rufu.

This means that striving to share Buddhism with others and expand our Soka movement, and to challenge ourselves in visiting and encouraging members—all these efforts help us break through our tendency to give in to our fear, our inability to believe in the potential of others and so on. Our Buddhist practice of chanting and continually taking action helps us to stop avoiding our weaknesses and instead face them head-on and, thereby, overcome our fundamental ignorance.

This is why Sensei says the following in his Columbia University address:

What then, are the conditions for global citizenship? … Certainly, global citizenship is not determined merely by the number of languages one speaks or the number of countries to which one has traveled. I have many friends who could be considered quite ordinary citizens but who possess an inner nobility; who have never traveled beyond their native place, yet who are genuinely concerned for the peace and prosperity of the world. (MDFA, 444)

Here, where Sensei refers to his “many friends,” he is talking about SGI members.

The second point I’d like to confirm is based on words from an educator that Sensei cites in his lecture:

Students’ lives are not changed by lectures but by people. For this reason, interactions between students and teachers are of the greatest importance. (MDFA, 448)

The relationship between mentor and disciple is the most vital element to developing the qualities of a global citizen.

In 2011, after the Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami, writer Miri Yu moved to the affected area and began carrying out activities to support the relief efforts. While a practitioner of the Christian faith, in an interview that appeared in the March 12, 2023, issue of the Seikyo Shimbun, she was asked how she decides what actions to take. She said that when she thinks of an idea of how she might help, she is guided by the thought of whether her actions will bring joy to the people in the local community. If she can’t picture people she knows finding joy from what she is planning, she figures it may not be a good idea. On the other hand, if she can see the faces of people she knows smiling and joyful, then she feels confident that she can carry out her idea.

When considering what makes her who she is, ultimately, she believes it’s because of other people—her parents, friends, teachers as well as generations of ancestors before her, including numerous people whose names she doesn’t know. Without even one of these people, she wouldn’t be who she is now. That’s why when she does anything, she always thinks whether her efforts will bring joy and hope to others.

In other words, if others can be compared to strings, she is a result of these strings being knitted together. It’s also possible to unravel these strings and to knit a new pattern.

Ms. Yu offers this example: The Chinese character for “string” combined with the character for “spring” or “fountain” creates the character for “line.” There are lines between self and others. In one sense, lines can function to divide and separate us from others, but they can also function to connect people together and direct us toward positive ways to live. When these lines that connect us are tied together, “springs” bubble forth.

Such lines not only connect those who are living but also connect us to those who have passed. Just before Ms. Yu lost someone dear to her, he said to her: “Why are you crying? There’s no way I would die and leave you.”

At that time, she wasn’t sure how to grasp what he was saying. But she now believes what he said is true. Even though he passed away, she still feels his presence. His thoughts, perspective and voice still remain with her. The resonance of how he lived hasn’t disappeared. She said that as long as she listens for that resonance, he continues to live on in her heart.

A great many people lost their lives from the sudden earthquake and tsunami. This author’s keen sensibility and observation about self and other reflects the Buddhist perspective of dependent origination.

The self is not separate from others and does not exist independent of others. The self is constructed through its relations and interactions with others. Truly the self is created thanks to the existence and influence of others.

The most noble relationship we can have with another is with our mentor; it is a relationship that produces the highest good. Our relationship with our mentor is what makes genuine character development possible.

Sensei emphasizes this point in his Columbia University address, saying:

In my own case, most of my education was under the tutelage of my mentor in life, Josei Toda. For some 10 years, every day before work, he taught me a curriculum of history, literature, philosophy, economics, science and organization theory. On Sundays, our one-on-one sessions started in the morning and continued all day. He was constantly questioning me—interrogating might be a better word—about my reading.

Most of all, however, I learned from his example. The burning commitment to peace that remained unshaken throughout his imprisonment was something he carried with him his entire life. It was from this, and from the profound compassion that characterized each of his interactions with people, that I most learned. Ninety-eight percent of what I am today, I learned from him.

The Soka, or value-creating, education system was founded out of a desire that future generations should have the opportunity to experience this same kind of humanistic education. It is my greatest hope that the graduates of the Soka schools will become global citizens who can author a new history for humankind. (MDFA, 448–49)

I believe this is the highlight of his lecture.

There’s a well-known saying: “Dig beneath your feet, there you will find a spring” (The Wisdom for Creating Happiness and Peace, part 1, revised edition, p. 39).

Just as this saying suggests, it’s vital that you give your all to your current challenges—as a student division member, in your studies and in supporting SGI activities. And while doing so and striving to understand Sensei’s heart and fulfilling your vow as a disciple, you will traverse the direct, most majestic path to becoming a global citizen.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles