“Winter always turns to spring.”[1]

“The wise will rejoice while the foolish will retreat.”[2]

“Prayers offered by a practitioner of the Lotus Sutra will be answered just as an echo answers a sound.”[3]

“Although I and my disciples may encounter various difficulties, if we do not harbor doubts in our hearts, we will as a matter of course attain Buddhahood.”[4]

“Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is like the roar of a lion. What sickness can therefore be

an obstacle?”[5]

These are among the passages that have inspired Soka Gakkai members for decades. Nichiren Daishonin’s encouragement has led millions to enact dramas of overcoming poverty, family discord, illness and feelings of powerlessness. These writings have served as a beacon of hope and courage for those who feel they have hit a dead-end. They inspire righteous indignation at the injustices plaguing humanity, enabling people to passionately work to transform society. Ikeda Sensei has said about studying Nichiren’s writings:

Strive to read even a passage or a page of The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin. I hope you will always seek to understand and learn from Nichiren’s spirit. [Josei] Toda used to say, “If you feel deadlocked, open The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin” and “When you’re exhausted, that’s the time to engrave the Daishonin’s writings in your heart.”[6]

In English, the Gosho consists of three volumes: The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vols. 1 and 2, as well as The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings. They primarily include Nichiren’s letters of encouragement to his disciples, comparisons of different Buddhist schools and treatises to government officials. Nichiren put his whole heart into each letter whether it was written to a woman who had lost her husband or to a government official. Each letter conveys his vow to awaken people to the correct Buddhist teaching and lead them to attain Buddhahood in this lifetime.

This month, we celebrate 70 years since the Soka Gakkai first published Nichiren’s writings, titled Nichiren Daishonin Gosho zenshu (The Complete Works of Nichiren Daishonin).

The Struggle to Preserve the Writings

The work of preserving Nichiren’s writings for more than seven centuries was taken on by dedicated disciples who wrestled with corrupt authorities bent on extinguishing his teachings.

Nichiren designated six senior priests to be responsible for preserving and transmitting his teachings. Following Nichiren’s passing in October 1282, Nikko Shonin, one of the six senior priests, worked furiously to compile his mentor’s writings and began to refer to them as “Gosho,” or honorable writings. But the odds were against him. The other five senior priests appeased the authorities and, as a result, turned their backs on the heart of their mentor’s teaching. They eliminated a number of his writings, specifically those that he wrote in the phonetic script addressed to lay disciples who couldn’t read classical Chinese. They felt such letters to ordinary believers, written in the Japanese vernacular, made Nichiren appear inferior to his elite contemporaries in the Buddhist clergy and reflected poorly on themselves. They failed to grasp their teacher’s deep concern for ordinary people expressed in these letters. They reused the paper they were written on or burned them.

Amid these obstacles, Nikko hurriedly collected Nichiren’s surviving writings. He even transcribed over 50 of Nichiren’s letters to make sure they could be preserved for the future.

During Japan’s march toward fascism in the lead up to World War II, Nichiren’s writings were once again in danger. Fortunately, by this time, the Soka Gakkai had emerged, inheriting the battle to preserve his writings. Founding Soka Gakkai President Tsunesaburo Makiguchi cherished his copy of Nichiren’s writings, devouring each passage and widely disseminating the teachings.

In 1943, when the Nichiren Shoshu priesthood was asked to enshrine a talisman dedicated to the Shinto sun goddess as their object of worship, they acquiesced. Mr. Makiguchi and Mr. Toda protested the priesthood’s cowardly decision, citing Nichiren’s treatise “On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land” to point out that this was precisely the time to remonstrate with the government. Mr. Makiguchi and Mr. Toda, determined to live based on Nichiren’s writings, resisted government suppression of their beliefs and were sent to prison as thought criminals.

This persecution formed the foundation of the Soka Gakkai’s commitment to developing faith rooted in Nichiren’s writings. The Nichiren Shoshu priesthood, on the other hand, cowered to the government’s demands and ultimately deleted 14 major passages from Nichiren’s writings they thought would offend the emperor.

Publishing the Gosho zenshu

One month after becoming second Soka Gakkai President on May 3, 1951, Mr. Toda announced his goal to publish the Nichiren Daishonin Gosho zenshu, a complete volume of Nichiren’s writings, by April 1952, which would mark the start of the 700th year since Nichiren established his teaching of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. Earlier editions of Nichiren’s writings had been published by other Buddhist schools, but they were missing significant works and contained phonetic errors.

The work of publishing the Gosho in less than a year was fraught with obstacles. First, with just some 5,000 members, the Soka Gakkai lacked financial resources. In addition, they were in a race against time to correct the mistakes in earlier editions and transcribe letters that weren’t included. On top of this, the Nichiren Shoshu priesthood refused to support the project. At the time, the priesthood’s priority was to raise funds to recast an elaborate ceremonial bell. Sensei recalls his mentor’s determination at that time:

Mr. Toda was resolved to compile and publish all the writings of the Daishonin so that his profound teachings might be open to all—without being twisted by other schools—so that Nichiren Daishonin’s Buddhism might be transferred eternally in its pure form.[7]

Ikeda Sensei and other core disciples responded to their mentor’s resolve and toiled nightly on the project. They also received support from former senior priest and Buddhist scholar Nichiko Hori. In the end, the first 6,000 copies were published in April 1952.[8]

A Teaching Illuminating Humanity

On July 3, 1945, Mr. Toda was released from prison to a devastated Japan. All other Soka Gakkai leaders had recanted their faith during the war to escape persecution. Mr. Toda noted that the reason for this was their lack of Buddhist study.

Throughout the history of Japanese Buddhism, lay people didn’t have a regular practice of reciting sutras or studying Buddhist scripture. The Soka Gakkai, however, revolutionized Buddhism by giving access to the Lotus Sutra and Nichiren’s writings to all people. Sensei writes about an episode where a member of a Nichiren Shoshu lay group attended a Soka Gakkai meeting in the 1950s. This person was shocked to see that Soka Gakkai members could fluently recite the sutra and had memorized passages from Nichiren’s writings. Sensei writes of his reaction:

“So, in the Soka Gakkai, everything is based on Nichiren’s writings, and the members are earnestly studying and trying to take action in accord with Nichiren Daishonin’s teachings!” [Tokuichi] Nozue quietly observed.

At the temple, the chief priest rarely encouraged the lay believers to study Nichiren’s writings. If they were mentioned at all, it was only when the chief priest would lecture on a certain passage during a temple meeting.

Nozue was astounded to find an organization like the Soka Gakkai. What amazed him the most, however, was that Soka Gakkai members were enthusiastically introducing people to Buddhism, driven by a burning desire to fulfill their mission for kosen-rufu and to help others become happy. He was deeply moved to see lay believers engaging in propagation, something even the chief priest of Hosen-ji did not do.[9]

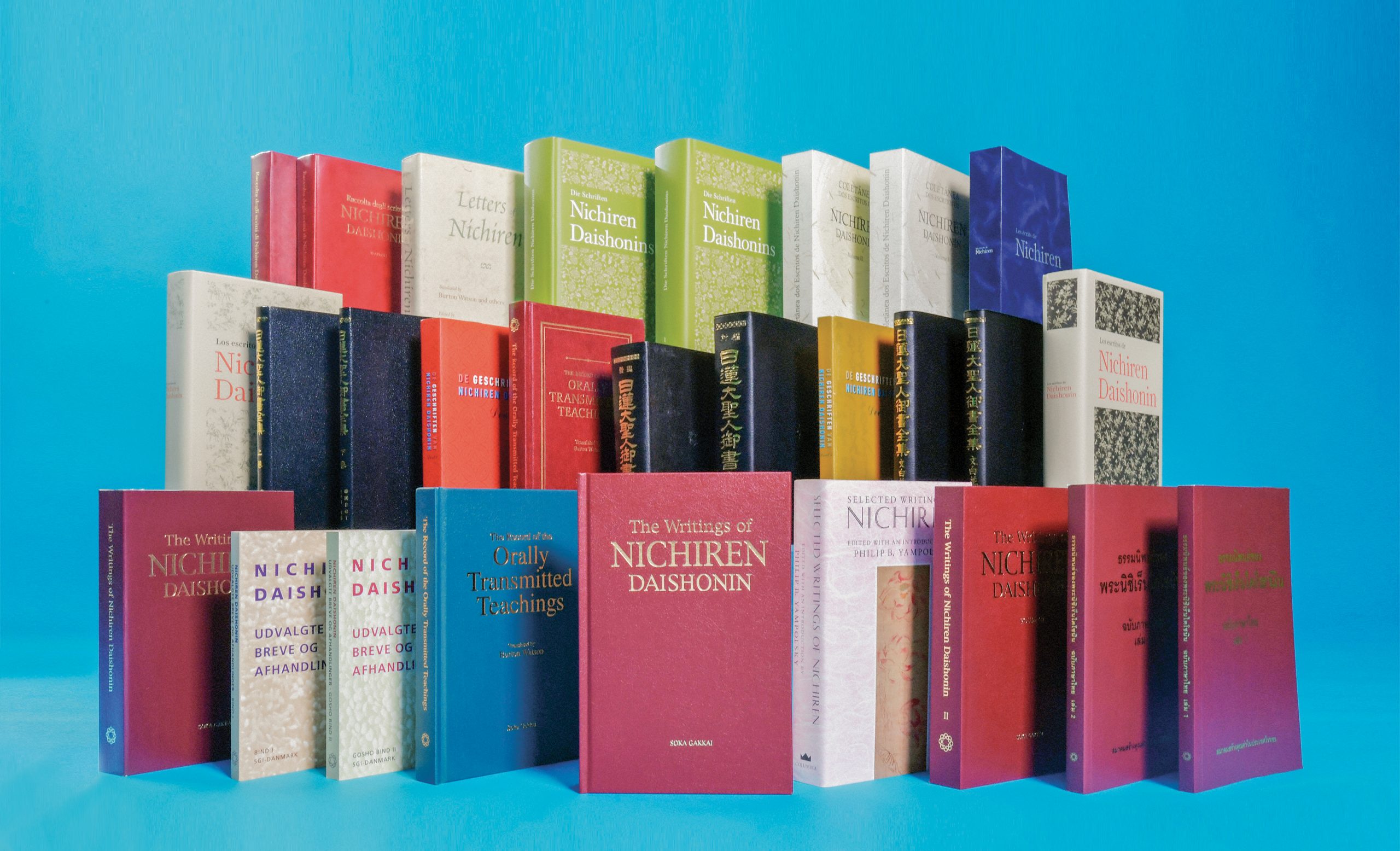

Now, 70 years after the Soka Gakkai first published Nichiren’s writings, they have been translated into more than 10 languages, emboldening millions of people worldwide to apply Nichiren’s teachings to everyday life.

Since President Toda embarked on rebuilding the Soka Gakkai after World War II, the faith of Soka Gakkai members has been rooted in Nichiren’s writings. Sensei addresses the source of the Soka Gakkai’s strength, writing:

Soka Gakkai activities and the Daishonin’s writings [go] hand in hand, and Buddhist study [is] related to daily life. That was the source of the Soka Gakkai’s resilient strength. In retrospect, this was made possible by second president Josei Toda’s publication of the Nichiren Daishonin Gosho zenshu. It opened a new epoch in which the correct teaching and principles of Nichiren Buddhism became established as a model of living for people from all walks of life.[10]

The Soka Gakkai’s determination to make Nichiren’s writings available to humanity has distinguished it as the Buddhist community most accurately disseminating the heart of Nichiren Buddhism.

—Prepared by the Living Buddhism staff

References

- “Winter Always Turns to Spring,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 536. ↩︎

- “The Three Obstacles and Four Devils,” WND-1, 637. ↩︎

- “On Prayer,” WND-1, 340. ↩︎

- “The Opening of the Eyes,” WND-1, 283. ↩︎

- “Reply to Kyo’o,” WND-1, 412. ↩︎

- Youth and the Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, p. 4. ↩︎

- The Human Revolution, p. 584. ↩︎

- See Ibid., p. 661. ↩︎

- The New Human Revolution, vol. 13, p. 101. ↩︎

- The New Human Revolution, vol. 30, pp. 130–31. ↩︎

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles