Living Buddhism: Hello, Wayne! Thank you so much for speaking with us today. As an architect, you design state-of-the-art buildings—most recently the Rhimes Performing Arts Center—and are currently working on a NASA test center project. Given your track record, it was surprising to learn that you were actually discouraged from pursuing architecture as a young man. What kept you going?

Wayne Thomas: So happy to speak with you today. That’s true—one of the first people I announced my ambitions to was my high school guidance counselor, who told me, “I don’t think there’s an architectural program in the country that will take you.” Fortunately, I had already learned the spirit to never give up through the SGI’s young men’s gymnastics group.

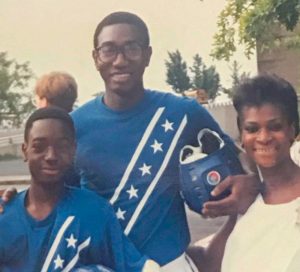

The first time I saw them perform was at Madison Square Garden in 1986, the year after my parents had begun their Buddhist practice. I was 12 at the time, and remember watching the young men perform in this human pyramid on roller skates, thinking, I want to do that. The next year, as everyone prepared for the 1987 Philadelphia Convention, I started showing up to practices, but it was a no-kids allowed kind of thing. I just went to the edges and did my push-ups and jumping jacks there and then, day by day, wiggled a little closer to the center. After a couple weeks, the adults realized I wasn’t going anywhere, that I was dedicated. When we built that pyramid in July of that year, my father was at the base, and I was at the top.

This is the memory, five years later, that blazed through me as my counselor dismissed my chances of becoming an architect.

No way! I thought. I got on top of the pyramid! A great university is gonna take me!

It sounds like your counselor’s words had the opposite of their intended effect.

Wayne: Yes, but it was still a battle, a process. For the rest of high school, I felt an overwhelming anxiety about my future. I took that anxiety to the Gohonzon, chanted Nam-myoho-renge-kyo for long periods. I decided to channel this anxiety into something I could make use of, some constructive action I could take. I began making these sculptures and drawings based on landscapes and buildings I’d seen over the years on summer road trips with family, or while visiting extended family in the Caribbean and New Orleans. I didn’t really know what I was doing. I’d never drawn a blueprint in my life. But by the end of high school, I’d put a portfolio together and submitted it to several universities, among them the Pratt Institute in my hometown, New York. The admissions team was blown away, saying the portfolio demonstrated extraordinary creativity. They admitted me with a substantial scholarship.

That’s wonderful! What followed from there?

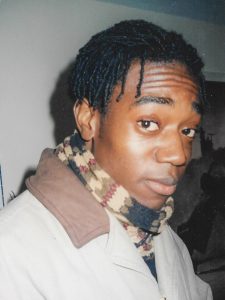

Wayne: Well, frankly, my first year of college, I felt totally in over my head. I was a commuter in a rigorous program at a prestigious arts school, and one of its only Black students. I faced all kinds of skepticism from without and intense self-doubts. My first year, I did poorly and was discouraged. I began considering dropping out. What kept me afloat were my brothers in the young men’s division who believed in me 100%.

How did they help you believe in yourself?

Wayne: There were these two guys supporting me, both young Black men, one a law student at Georgetown University and the other a film student at New York University. Their level of support floored me. Ikeda Sensei’s poem “To My Beloved American Friends—Youthful Bodhisattvas of the Earth,” was written in June 1981, in Long Island, and was the anthem of SGI-New York. Despite facing similar prejudices and doubts in their own university experiences, you wouldn’t know it. Their confidence and commitment to demonstrate actual proof of the practice in their lives, as disciples of Sensei, and to uplift me to fight with the same spirit, was something else. In short, I thought they were cool as hell and started chanting to do the same, to see beyond my own hardships and uplift the young men around me who were struggling to believe in themselves.

Chanting and taking action in this way, even when I felt I was pushing myself to my very limits, helped me move beyond my own anxiety and open up untapped reserves of creativity. My second year at Pratt, I took off, excelling at such a level as to get the attention of the Dean. My second year, she awarded me the Studio Award, usually reserved for seniors, and called three of New York’s top architects to tell them, in short: “You need to give this kid an internship.”

Chanting and taking action in this way, even when I felt I was pushing myself to my very limits, helped me move beyond my own anxiety and open up untapped reserves of creativity.

We understand you have a story about Sensei that demonstrates the kind of spontaneous creativity that you were developing.

Wayne: Absolutely. After Sensei gave his second lecture at Harvard University, in September 1993, titled “Mahayana Buddhism and the Twenty-First-

Century Civilization,” he came to Boston to attend a dinner conference. I was there with three of my brothers in faith, representing New York. These were the same young men who had helped me develop my faith, and who had encouraged me constantly while I was working toward my bachelor’s at the Pratt Institute. To me, we represented not just New York but the future.

We were representatives of a new generation of Black youth who had pushed ourselves to enter cultural and academic institutions that had historically excluded us. Sensei gave powerful guidance, encouraging us to become people possessing hope-filled spirits and fine characters, affirming that to win in daily life was to win in faith.

Then there was this beautiful chorus that sang “Let the River Run.” In the middle of it, this guy, a young Black performer, came in with a rap. In the middle of it, he stops and, unscripted, points to Sensei, as if to say, You’re up. And Sensei just gets up, grabs the mic and starts rapping his own verse in Japanese. Then he crosses his arms, like Run-DMC and points back to the guy, like, You’re back, and the guy takes back up the verse to close it out. Seeing that, I have to say, me and my brothers, who’d come of age in the golden era of hip-hop, we went ballistic. This hit us in a real personal place. Like: This is my mentor, and he’s so relatable, so down to earth. That experience solidified for me my full acceptance of Sensei as my mentor. I realized: I am SGI-USA. It’s mine. I’m a part of this. It’s not separate from my own life. Sensei’s heart is so embracing, so down to earth. I realized that this organization is what we, disciples, make of it.

That is awesome. Underlying artistic spontaneity is usually a high degree of self-mastery. What is your prayer when designing a building?

Wayne: I chant to infuse the spaces I’m designing with the life state of the Buddha. The Gohonzon, the object of devotion, is infused with the life condition of Nichiren Daishonin. But that condition is activated only when we engage with it. I try to bring that engagement into my daily life, into my projects, so when people enter those spaces and engage with them, they can feel it somehow—the Mystic Law.

What does this look like practically?

Wayne: I think about the spaces I design from the standpoint of the people moving through them. There’s nothing wrong with a flashy, iconic look, but that’s never my priority. What I want above all else are spaces that facilitate creativity within and among the people in them. As an example, the Rhimes Performing Arts Center has certain studios with 40-foot walls that can be lifted swiftly into the ceiling to expand space and facilitate collaboration. It’s subtle, but the spaces are brought alive through the interactions of the people in them. Of profound inspiration to me has been Sensei’s lecture at the Institut de France titled “Creative Life,” whose margins I’ve marked up and down with notes over the years. He mentions the traditional form of Japanese poetry called renga, in which many people would gather to create a poem, contributing verses to the poem and linking them together. Of renga, Sensei says, “[It] could not have come into being without a space where many people could gather and literally bring out connections among the place, themselves and their verses.”[1]My prayer for the Rhimes Center was to support the performers and the audience in bringing out these kinds of connections.

Photo by Allen Zaki.

What motivates you to dig deeper and push yourself to new heights?

Wayne: In 2017, my wife, Caroline, and I attended a lecture by an SGI representative from Japan. He hit some points we were familiar with, encouraging us to show actual proof, to support kosen-rufu, to lead kosen-rufu from America. I went home thinking, “Great meeting!” but not much else. But through encouragement, we began to think about what it would be like to become people who could support the SGI movement into the distant future. I began to dream of a nature and culture center of the caliber we have in Florida being built in other states. I began to think about having an art museum of the same caliber as the Fuji Art Museum here in the states. Caroline and I renewed and deepened our vow to become people who could respond to Sensei’s vision to build a society rooted in the dignity of life and contribute in every way possible.

What are your determinations for the future?

Wayne: My personal determination is to create a harmonious family that is dedicated to kosen-rufu! I’m really proud of both my girls, Nala and Sadie, who I feel have blossomed into self-motivated, compassionate people grounded in this profound philosophy of life. I am determined to never abandon my practice, to become an example demonstrating the profundity of Buddhism and to protect our organization at any cost for many generations to come.

References

- A New Humanism: The University Addresses of Daisaku Ikeda, p. 7. ↩︎

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles