Lecture on “The Quintessence of Thought and Philosophy”‘

On August 31, 1962, just over two years since becoming Soka Gakkai president, Ikeda Sensei began a five-year series of lectures to student division members on The Record of the Orally Transmitted Teachings, a text he referred to as “the quintessence of thought and philosophy” (The New Human Revolution, vol. 6, revised edition, p. 278).

For several years leading up to this date, Sensei wanted to offer lectures on Nichiren Daishonin’s writings to student division members. In fact, second Soka Gakkai President Josei Toda had given lectures on the Lotus Sutra to Tokyo University students starting in 1953. This group was known as the Lotus Sutra Research Society of Tokyo University, a prelude to the Soka Gakkai student division. President Toda resolved that Soka Gakkai members who were university students would become influential leaders in society with a firm grasp of the Lotus Sutra’s essential message of the infinite potential and dignity of life. At the end of his final lecture in September 1955, Mr. Toda told the participants that if there was something they didn’t understand to ask Daisaku. Since then, Sensei wanted to continue his mentor’s efforts to foster the faith of student division members.

On July 16, 1962, during a discussion between Sensei and student division members, one student requested that Sensei lecture to them on Nichiren’s writings. Sensei responded, as if awaiting this request:

Let’s do it! … Unless you study Nichiren’s writings thoroughly and come to know the profound depths of the Daishonin’s teachings, there’s really no reason for the student division to exist. Studying his writings is of utmost importance. Let’s study together. (NHR-6, 256)

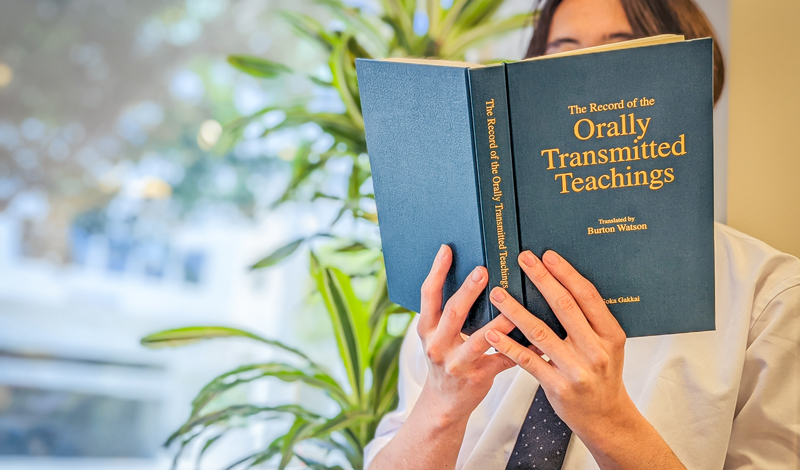

Sensei decided to lecture to the students on The Orally Transmitted Teachings—a compilation of the Daishonin’s lectures on key passages of the Lotus Sutra—feeling that this work “fully eludicates the principles of Nichiren Daishonin’s Buddhism—its view of life, religion and the cosmos” (NHR-6, 278).

In 2004, The Orally Transmitted Teachings was released in English, translated by Burton Watson, a renown translator of classical Asian literature. In 1992, after completing his translation of the Lotus Sutra, he met with Sensei and discussed the significance of the Lotus Sutra’s philosophy and the possibility of setting to work on translating The Orally Transmitted Teachings into English. On this occasion, Sensei said of this work by Nichiren:

Is the very marrow of the “eighty thousand teachings” of Buddhism. It is the very heart of Nichiren Daishonin. …

If you truly understand even one part of [The Orally Transmitted Teachings], the Lotus Sutra will become clear to you. True understanding is not merely an intellectual operation; it is attaining deep intuitive wisdom, the kind a great doctor has when [they] feel [their] patients pulse and totally and clearly understands [their] physical condition, grasping it, literally, in [their] hands. (August 17, 1992 World Tribune, p. 4)

This is the work Sensei decided to introduce to the students who would venture out into the world and contribute to developing a society undergirded by the humanism of Nichiren Buddhism.

Explanation of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo From Sensei’s Lecture

The following is an excerpt from Sensei’s lecture on The Record of the Orally TransmittedTeachings adpated from The New Human Revolution, vol. 6, revised edition, pp. 285–96.

The reason TheOrally Transmitted Teachings begins with a discussion of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is that Nam-myoho-renge-kyo is the basis of all sutras and the heart of the Lotus Sutra. Concerning Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, the Daishonin tells us that namu derives from Sanskrit, the literary language of ancient India, and that it translates as ‘dedication,’ meaning to devote one’s life. …

Everyone is devoted to something. The samurai retainers of old were devoted to their lords, and during World War II, the Japanese people were called on to give themselves utterly to their nation. Today, we see people devoted to their work or to their company, as well as those who give up everything for the ones they love.

The crucial thing to remember is that what you devote yourselves or give your lives to, is what determines whether your lives will be happy or unhappy. The Daishonin teaches us that the highest, most fundamental kind of devotion is to the Gohonzon of the oneness of the Person and the Law—that is, to Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. …

More specifically, we might say that this means to remain dedicated throughout our lives to realizing kosen-rufu, to take as our life’s purpose the widespread propagation of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo and the Gohonzon. This is the path that leads to absolute happiness.

I’m sure some of you regard expressions such as “not begrudging one’s life” and “dedicating one’s life to Buddhism” as encouraging a sort of self-sacrifice, some kind of tragic self-immolation. But the state of mind described here is a state of complete, self-assured calm and peace, a state utterly without fear. It is a feeling as expansive and serene as the clear blue sky, a fullness of hope, joy and total satisfaction—a state of being ultimately free and true to oneself.

Devotion to the Mystic Law means breaking through your lesser self, the small you that has been driven and hounded by all kinds of petty, selfish wants and desires. It means returning to your greater self, the self that is one with the universe, as vast as the cosmos.

When you accomplish that, you will shine with your highest potential. The process by which this comes about is called human revolution.

• • •

Nam or namu is a phonetic transcription of the Sanskrit word namas … while Myoho-renge-kyo is the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese translation (miao-fa-lianhua-jing) of the Sanskrit title of the Lotus Sutra. In other words, Nam-myoho-renge-kyo comprises the languages of ancient India and China.

In the center of the Gohonzon are the words Nam-myoho-renge-kyo Nichiren. And Nichiren is Japanese. In addition, among the various figures representing the ten worlds, the names of two guardian deities—Wisdom King Immovable and Wisdom King Craving-Filled—appear on the right and left sides of the Gohonzon, respectively, in Sanskrit letters. This means that the Gohonzon, which is to be spread throughout the world, is written in the script of three countries: India, China and Japan. In the Japan of the Daishonin’s time, this represented the entire world.

Whenever I read The Orally Transmitted Teachings, I am deeply struck with the awareness that Nichiren Buddhism is not meant for one country or people but for all of Asia and, indeed, the entire world. I am also convinced that this passage demonstrates that kosen-rufu in Asia and the world can in fact be achieved.

The task of realizing this goal falls to you student division members. I want each of you to seriously consider how we can spread Nichiren Buddhism around the globe and lead all humanity to happiness.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles