In The Analects, Confucius states, “At 60, my ears were obedient.” By that age, Confucius had developed the ability to listen to anyone. His “ears” were no longer biased by ego, impulse or pride. He had attained a deep inner confidence in his life’s purpose—allowing him not just to “hear” but to truly listen to others.

Regarding this, Ikeda Sensei once said:

Returning to the phrase “my ears were obedient,” listening with an open mind to the opinions and ideas of others is not easy. Whether the ability to do so depends on one’s state of life or one’s depth of experience, what matters most is that we pay close attention to what others have to say. Personally, I always make an effort to be a good listener.

Many believe that as we get older, we become increasingly attached to our experiences, growing more stubborn and unyielding as the years pass by. But it is precisely in our advanced years that we should give full play to the wisdom we have gained through our experiences and listen with an open mind to what others have to say. I feel that I have become an even better listener the older I get. (A Record of My Life, p. 42)

Buddhism teaches of seven essential elements of practice, also called the “seven kinds of treasures,” which consist of “hearing the correct teaching, believing it, keeping the precepts, engaging in meditation, practicing assiduously, renouncing one’s attachments and reflecting on oneself” (“On the Treasure Tower,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 299). The first of the seven, “hearing the correct teaching” means listening to Buddhism, but Sensei expands the meaning explaining that “on a broader scale, it underlies the importance of listening to others” (A Record of My Life, pp. 42–43).

SGI members lend their ear to others, validate their experiences and give them the courage and confidence to continue forward. Sensei says: “For those who are suffering, just being heard can help lighten their burden. Having someone warmly listen to what one has to say is in itself encouragement to go on” (The Wisdom of the Lotus Sutra, vol. 6, p. 92).

As we look to advancing our kosen-rufu movement far into the future, it’s vital to open our ears to the voices of the youth who will lead it.

Sensei explains why:

Nichiren Daishonin was determined to relieve the suffering of all people, without exception. This was his immense compassion. That spirit of boundless compassion and tolerance is the essence of Nichiren Buddhism.

But however excellent a teaching may be, without successors to inherit it, it cannot be passed on to many people.

In another part of “On the Buddha’s Prophecy,” Nichiren writes: “Even when … [Buddhist] priests set out from Japan to take some sutras [back] to China, no one was found there who could embrace these sutras and teach them to others. It was as though there were only wooden or stone statues garbed in priests’ robes and carrying begging bowls” (WND-1, 401). (May 2021 Living Buddhism, pp. 58–59)

With the future in mind, Living Buddhism sat down with four young people from across the country to listen to their perspectives about what it takes to reach the hearts of a new generation. Please join us in listening to what they have to say.

Living Buddhism: Thanks for joining this conversation. Today, we’re here to listen. To start, can you each introduce yourself and share what sort of impact Buddhism has had on your life?

Ella Redmond (New York):I’ve been practicing for four years. I met someone at a jazz bar who told me that he was Buddhist. I laughed at him because I thought he was joking. But as he spoke about Buddhism, I was pretty amazed. He invited me to a meeting, and it was really great.

The greatest benefit I’ve experienced is my life condition. I’ve stopped comparing myself to others, which, as a musician, is really hard to do. My Buddhist practice has given me the confidence and faith in myself to trust that everything is happening exactly as it is supposed to.

Kenneth Randall (Chicago): I was introduced in college about eight years ago. I was inspired by the way one of my good friends dealt with her challenges and lived her life. She took me to a meeting, and I started practicing. We were in the same district for many years. I have profound appreciation for her and her friendship. I’d say the greatest thing I’ve gained from my Buddhist practice is a spirit to challenge myself. Regardless of what happens, I can refresh my determination each day.

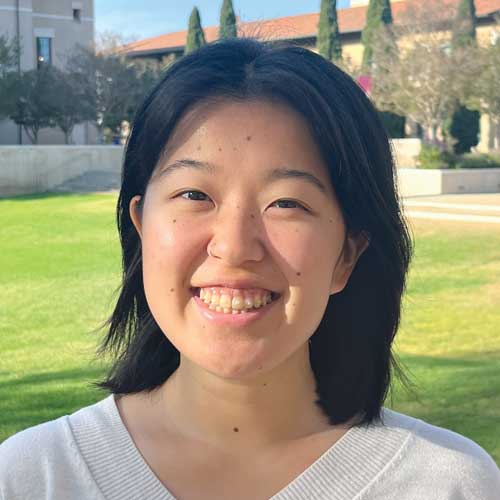

Ayu Nakazaki (Orange County, Calif.): I was born and raised in Honolulu, Hawaii, but now live in Orange County in my fourth year at Soka University of America. I was born into this practice. I think the greatest thing I’ve gained is deep relationships with my family and friends. With my Buddhist friends, even if I’ve just met them for the first time, I feel like I can trust them immediately. I think a strong sense of community with people that share the same values is a huge benefit.

Eamon Weber (Denver): I was born and raised in Denver. I also grew up in the practice, but I started chanting on my own when I was 14. I was a delinquent in high school and was like, I need to get it together. So I started chanting. The greatest thing I’ve gained is conviction and a solid sense of direction. Many times, I felt lost, asking myself, What am I going to do with my life? But now I can call my friends in faith and ignite my fighting spirit.

I’m a musician and going to school for audio engineering. It’s an unstable career path, but having 100% faith in the Gohonzon and having conviction that no matter what, things are going to be OK is something that I’m very appreciative of.

Thank you all for sharing. In the June Living Buddhism, we are talking about the courage to listen to the youth. What are your thoughts on this? Do you feel that your generation is respected and listened to?

Kenneth: I think there is a gap between the older generations and the younger generations. Younger generations are seen as soft, but I think that discredits what we go through and prevents us from being heard about the things we are struggling with.

In the SGI, at least for me, I feel respected. I feel like the focus is on us to change the world. The men’s and women’s division members want to support and challenge us to unlock our potential. If the same kind of support extended to youth in society, I feel like our world would move in a much better direction.

Eamon: Definitely in the SGI, I feel heard. I’m very appreciative of the SGI community and the voice that I have. If I need someone to talk to, there is always someone there to listen. In other areas of my life, it depends. I used to work at a restaurant, and there were older folks in the back of the house where I worked whom I felt were really looking out for me even though there was a language barrier. But then, I’ve had some bosses where I’ve felt like there are many expectations put on me but no guidance—I’ve been treated as an output machine.

Ayu: As youth, we need a lot of validation and affirmation because we don’t feel confident in ourselves. We are worried about how people perceive us. Growing up, I struggled with my self-confidence, but I had leaders who would praise me and say things like “You are so amazing” for doing something as simple as introducing myself at a meeting. For that reason, I think growing up in the “garden of Soka”

is so important.

As the times change, one thing that I think the older generations can keep in mind is inclusive language, especially when it relates to gender. So maybe instead of saying “young women and men” we can say “all people or youth,” which are terms everyone can feel included in.

Those are some really great points. As you all know, we have an incredible philosophy and practice. The question is, what is key when introducing young people today to it?

Ella: I think a lot of it comes from trust and becoming genuine friends with people. Trust is a really big thing. Being genuine and showing your care for someone is so important. For example, if you make plans with someone, being on time goes a long way.

Eamon: I agree. People in my generation are wary and skeptical about trusting everything they see. It’s hard to trust something unless you have a friend that you respect that can ease your skepticism.

Many youth are ambitious and want to do many things, but they hold themselves back based on their self-limitations. People are seeking to unlock their potential and overcome their obstacles, but they don’t know how and often don’t trust organized religion—or organized anything!

Ayu: Yep. Our generation grew up on the internet, so there’s a lot of things that we are taught not to trust. Having someone who is really sincere and genuinely open up about themselves first—that is really important.

I think our March discussion meetings were so joyful because it was an open discussion with less structure. It was organic and spontaneous, and that was beautiful. Guests felt like, Wow, these people are so genuine and they just want to connect. The natural atmosphere built trust with our youth friends.

Kenneth: That’s true. Two of my roommates came out to the young men’s division summer hangouts last year and enjoyed it, but when it comes to more formal discussion meetings, they hesitate. I think it’s for a variety of reasons but mostly because they don’t trust organized religion. I think a space where young people can come and talk about their problems and open up their lives would be really helpful as a first step.

Ella: Yeah, I think one-to-one dialogue is so important. When I introduce people, I never use the word religion. I say “my Buddhist practice” or “Buddhist philosophy.” I think the word religion sometimes freaks people out, but that’s why one-to-one dialogue is so important, especially in our political climate where people are so divided and refuse to speak to others who are different from them. We need to have compassion for all people—even those who we don’t agree with—to understand where they are coming from. That goes for youth, too. There are reasons why they are skeptical about certain things.

You’re right, every person is so different. There is no cookie-cutter way to introduce people to Buddhism.

Eamon: At the end of the day, it is a grassroots organization, so it’s up to each individual. It’s about embracing each person where they are at. I have roommates who sometimes chant or do gongyo with me but are not necessarily interested in joining the SGI. I just embrace them where they are, and I think they feel that sincerity.

Ayu: That’s been my experience, too. I have a friend who naturally opened up to me about their struggles. I shared how I navigate my own struggles without explicitly saying I practice Buddhism at first. As our friendship grew, they randomly told me that they would like to practice Buddhism. It was very organic.

Whenever I’m trying to share Buddhism with someone, I have to pray to deepen my compassion for them. It’s not just that I want this person to come to a meeting or start chanting. Ultimately, I want them to become happy, and I want to deeply feel that before I take any action. Youth are very perceptive. They can feel when someone cares about them or is just trying to make them do something.

Kenneth: I know when I first started chanting, I had a good friend who I felt like supported me regardless of what my challenges were and they listened to me. I felt like they cared about what I was going through.

Thank you all for sharing. That authenticity and genuine care seems to be most important in developing friendships with young people today. What do you think about the language we use to introduce others?

Kenneth: I think that’s a big challenge—articulating and translating Buddhism in a way that will resonate with youth so it doesn’t feel too formal and we can meet them where they are. For example, one time I met a young boy at the Elementary School Division Conference at the Florida Nature and Culture Center. He didn’t want to be there, and it was a challenge to get to know him. But he liked the video game Roblox. I don’t play Roblox, but I challenged myself to learn about it, and I was able to connect this passion of his to our Buddhist practice. Just like how in Roblox, you achieve different levels, I told him we can “level up” and win in our own lives by chanting. Speaking to someone in relatable terms goes a long way.

Eamon: I think if you can relate it to how someone can personally overcome their struggles, it can pierce their hearts. I know one thing that doesn’t work… long lectures! I think people tune out when there is a lot of talking and not a lot of listening. I think when speaking about Buddhism, we should break it down and talk about how it can help them in their personal struggles.

Ayu: Yeah, authenticity is important. I was hanging out with a group of friends, several who were not SGI members. In the conversation, a friend who is Buddhist shared that when they feel overwhelmed, they chant daimoku! And I immediately felt like it would make everyone in the group confused and uncomfortable, but actually they all thought it was lovely and became curious about the practice. I think it was because my friend who opened up about chanting was so genuine about it.

What kind of language do you use to share Buddhism with your friends?

Kenneth: I share how chanting helps activate us in the morning to focus for the day. I sometimes use the term “locking in.” For me, that means focusing on what I need to do and summoning the courage to take action to achieve those things. This is the power of chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo!

Ayu: I was at a meeting the other day, and they were talking about how the Gohonzon is a mirror. That might resonate with some people, but what does that actually mean? I think we need to find new ways to describe the Gohonzon or why we chant.

Eamon: I’m a musician so this is how I like to describe chanting. It’s like a baseline. In music, there is a call and response—the bass drum reacts to the kick drum. If you think about it, the universe is playing a kick pattern. And in life, because we have responsibilities like jobs and school, there are many things we are balancing, and it’s hard to hit every single kick drum and hit on beat every time for a full 16-hour day. But chanting, it refreshes you. It’s like bringing a metronome fresh into your head where you never miss a beat. It’s like training your life to align with this kick drum of life.

Ella: That’s a great way to explain it. At the end of the day, when I first started practicing, whenever someone shared an experience, I was so moved and felt like Buddhism really works. I think when trying to share with younger people, the most important thing is life condition and daimoku to meet people who are seeking. And if people see your life condition and see how genuine and compassionate you are, they will feel it. It’s so important that we share with youth. They need to hear about it.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles