Living Buddhism: Jonathan, you’re an assistant film editor by trade and a budding filmmaker. We understand you just got back from a trip to Malaysia to gather material for a documentary on a very personal subject—your mother. Would you tell us about this?

Jonathan Cheng: Sure. My mom’s story is one I’ve wanted to tell for some time—or rather, to hear it told by those who can still tell it. I live with her here in Manhattan but don’t know half as much as I’d like about her life. I was in my junior year of high school, applying to film schools across the country when she exhibited the first signs of Alzheimer’s. I narrowed my search to local colleges, enrolling close to home—close to her, my brother and my father. As I gained a grasp of the fundamentals of storytelling, my mother rapidly lost her ability to tell her own.

You were born into a family that practices Nichiren Buddhism, but it wasn’t until college that you began practicing it in earnest. Is that right?

Jonathan: In my first year, that’s right. Like many, it was a time in which I questioned everything—my potential as a filmmaker, my chances of making it in a city like New York, my responsibility as a son in a family in which no one was employed. Should I drop out and find work? Move home and help out? Doubts and insecurities were endless. The first thing I thought to do was call home, to call my mom. Talking to her, I realized just how far her Alzheimer’s had advanced and understood that she could no longer guide me out of a crisis. For the first time, I fully—and viscerally—appreciated the pillar of faith my mother had been for our family. It shook me to my core.

If not her, who could you talk to?

Jonathan: My brother. I called him that same evening with a rising sense of panic. I unloaded and he listened. “Honestly, I don’t know what to say that will help,” he said. “But have you tried chanting?”

Out about on campus, I ducked into an empty side room, faced the wall, and did just that. For maybe 15 or 20 minutes, I chanted, after which I felt lighter, my desperate, spiraling thoughts having steadied and focused into one simple determination that went something like: I’m just gonna give it a shot. From this point on, for the first time in my life, I centered myself on my Buddhist practice with the growing awareness that I would need to become a pillar for myself and my family. I kept at it, graduating in 2015 and landing work in the industry.

Circling back on your mother and her story—you never heard it firsthand?

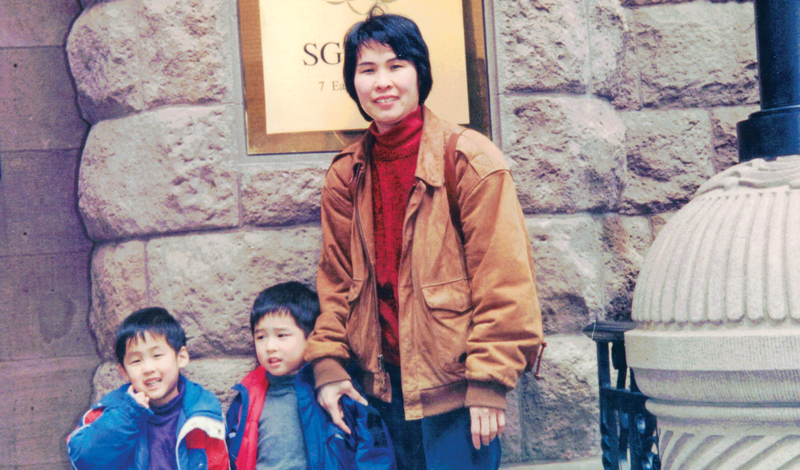

Jonathan: Even when well, she wasn’t one to discuss herself. The eldest of six, she acted from a young age as a second mother for her younger siblings, who depended on her. When she moved from Malaysia to the States in her 30s, she continued to work hard—very hard, with the same concern for others, to lay a foundation for the life of her family. I knew most of the key pieces of her story in the States—how she met my father, for instance, working in his small shop producing film. But I knew very little of her life in Malaysia, where she was born and raised and began practicing this Buddhism.

In October 2025, I returned from Malaysia, a two-and-a-half-week trip spent speaking with extended family. I was hoping to find my mom’s sponsor—the woman who introduced her to Buddhism. Though I could not locate this person, I found others, women who’d practiced Buddhism with my mom in their youth. They shared their memories of her, of who she was to them—hardworking and spirited, a devoted friend. These matched with the woman I knew, the mother who raised me and helped me reclaim a part of myself. Collecting these stories guided me in finding a way to tell my mother, “I love you.”

You recently had a transformative experience with your father as well.

Jonathan: Yes. My father was a stay-at-home dad, retiring to care for my brother and me while my mother worked. Because of my mom’s long work hours, we rarely came together as a family—rarely sat together around the dinner table. My father, a stoic man, showed, rather than spoke, his love. When I began working full time and my hours grew long, I came home to a plate of food set out on the table. When my mother fell ill, my father worked through the frustration and pain while raising my brother and me. He was, in his quiet way, a rock for our family—in consistent good health, supporting behind the scenes. So it came as a shock when his health plummeted in March of 2020. Within a couple days, he suffered a stroke and was hospitalized. There, he was diagnosed with both pneumonia and COVID-19.

What did that mean for you as a family?

Jonathan: Most significantly, it meant my brother and I became the primary caregivers for our mother. Fortunately, I was able to come home—the pandemic had put me and just about everyone in film out

of work—to support in whatever way I could. It also was a crisis for me, having made a new year’s resolution unlike any I’d made before: to strengthen my relationship with my father. This seemed to me to have become truly unlikely under the circumstances—pandemic-era restrictions barred me or anyone from visiting him in the hospital.

What did you do?

Jonathan: I sought guidance from a senior in faith who encouraged me to simply tell my father what I felt was important for him to hear—that me, my mom and my brother were OK. Chanting ahead of each call with my father, determined to open my heart, I realized there was something else he should hear—something I wanted to say. “Mom is alright,” I’d begin. “Melvin and I are working together, taking things in turns. Please don’t worry about a thing. I love you.”

I did not expect my dad to say “I love you” back, and he didn’t—not at first. But as we spoke, he did, somewhat awkwardly, incredibly, begin to say those words. They filled me with hope and I looked forward to his coming home. Though his health was on the decline, I refused to believe that he would not recover.

But he did pass—in April, correct?

Jonathan: Yes. But just before he did, an odd thing happened—he called me, not something he’d ever done from his phone in the hospital. It had always been me who called him. But he called and I answered and said hello, but did not hear anything back from his end of the line. I knew from the faint hospital sounds in the background that the call hadn’t dropped. “Dad?” I said. Nothing. I called the front desk and was transferred to the head nurse of the ICU, who transferred me again to a nurse in his ward. As the phone rang, my mind raced, wondering what could have gone wrong. The nurse who answered put me immediately at ease. She was at my dad’s side. He looked just fine, she told me. I explained about the call—how my dad had called but said nothing. “He really is alright,” she said. “I imagine he just wanted to hear your voice.” She handed him the phone and I assured him we were all alright. The next morning, the hospital called: My father had passed away.

Could you share what you felt in that moment?

Jonathan: Honestly, at a loss. Now he was gone and I was left to wonder how I could strengthen a relationship with someone who was no longer here.

What’s more, I had been chanting for him to regain his health. He hadn’t. My brother and I—still grieving—were officially our mother’s main caregivers. I moved back in with my mother and brother. Given this new reality, my lack of employment became a pressing matter. I felt the urge to blame everything around me for my unhappiness and give up.

Clearly, you chose another route.

Jonathan: With some help, I did. I received tremendous support from my SGI community. For the second time, I sought from a senior in faith about my relationship with my father. He remarked that my father must have been a great person, given how I turned out. He reminded me that Sensei spoke often in his heart with his mentor, Josei Toda, after his mentor had passed. There was no reason, then, he told me, that I could not engage in a dialogue with my father.

Taking this to heart, I began to talk to my father in this way, assuring him, as I had in his final days, that everything would be alright—that I would find a job to support our family. I determined to be happy, as my father would have wanted me to be—to make him proud. Chanting this way, I began to realize that I had already greatly strengthened my relationship with my father, and there was no reason why I could not continue now to strengthen it further. There was no need for regret.

As a young men’s leader, I increased my efforts to connect with the young men in my chapter, biking to them to avoid the subway and its heightened risk of exposure. I remember biking from Manhattan to Queens to encourage a friend to get his SGI-USA publications, which he did. On my way home, I got a call from my producer: a project that had been long on hold was now proceeding. I could work from home, he told me—perfect for taking care of my mom. I was offered a coordinator role, a promotion from my pre-pandemic position—an immediate benefit of my own efforts to support others.

Alright! And then?

Jonathan: I continued supporting behind the scenes supporting Soka Group shifts, honing skills that earned me the trust of everyone at work. In 2023, I took things up a notch, chanting abundantly every day and visiting young men, members and guests. Upping my efforts in the Soka Group, I further honed my courage, preparedness and swift, unhesitating responsiveness. I reconnected with friends with whom I’d lost touch, supporting them to an extent they tell me is rare. As I did this, something came increasingly into view—a dream I’d long held without ever managing to believe in it fully.

That March, my boss offered me a new contract as the coordinator for the next season of a popular show. Drawing forth my courage, I asked if, instead, a new position could be created, that of an apprentice editor.

My producer appreciated my honesty and commended me for speaking up about my worth. Three months later, I received an official offer for the apprentice editor role—an entry into my dream job. This position allowed me to join the editors’ guild, with better health insurance and benefits. It was undeniable proof of the fortune I had created through my practice.

And now?

Jonathan: In the summer of 2024, I transitioned again, finishing one season and preparing for the next with a new producer. One morning, my producer called not only to confirm I’d be returning, but to tell me I had been promoted—from apprentice editor to assistant editor, my dream role, something I thought would take years. He and my colleagues said they were happy with my work and wanted to help me move further in the industry.

What has this experience taught you?

Jonathan: Ikeda Sensei says: “The Daishonin encouraged the Ikegami brothers… ‘Could there ever be a more wonderful story than your own?’ (“Letter to the Brothers,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 499) … Our individual experiences of triumph over our problems give courage and hope to many others” (The Wisdom of the Lotus Sutra, vol. 2, p. 26). I grew up being ashamed of my story. Now, I’m embracing it—realizing it’s uniquely my own and meant to encourage others.

Earlier this year, a friend who had always insisted he wasn’t interested in Buddhism asked me about how I deal with being the caretaker for my mother with Alzheimer’s. His grandmother, who was living with dementia, had made him think of me. I told him honestly that Buddhism is what gives me the life condition to handle these things. Other friends, too, have told me they thought of me when their parents faced similar illnesses. It’s made me reflect deeply on my mission—how my experience can help others. It is my story, and it is why I have something to say.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles