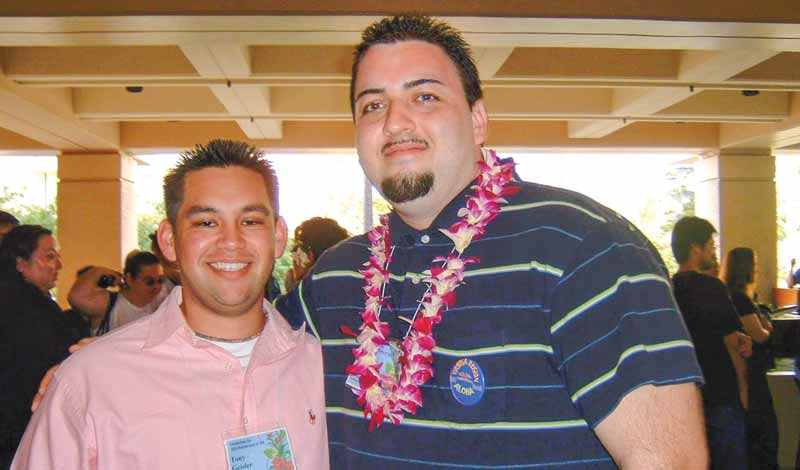

Never give up—(L–r) Jason Lions and his former young men’s division leader, Tony in 2005. 20 years later, they attend the Men’s Division Conference at the Florida Nature and Culture Center, Weston, Fla., April 2025. Photos courtesy of Jason Lions.

Jason Lions

Los Angeles

Throughout my early years, poverty and violence were daily realities of my life. My family moved several times from one roach-infested place to another, eventually settling in a rough area in Norfolk, Virginia, Often faced with life-threatening physical abuse from my father, I would wake up most days wondering if it would be my last.

Somehow my mom had hope, and she always encouraged me to never give up. For many years, she worked 12-hour night shifts to support our family, often sleeping only four hours a day so that she could see my brother and me off to school and make us dinner. After realizing that her courage stemmed from her Buddhist practice, when I was 8, I started chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo and attending SGI-USA activities on my own.

Our family situation improved after my father left, but as a teenager, the violence that surrounded my early years erupted in devastating ways. I was diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder and depression. I developed daily panic attacks, insomnia, and compulsive behaviors. I also became bedridden, was often unable to interact with people and would not speak for days.

By my early twenties, I lost my will to live, had completely withdrawn from everyone and was wasting away physically. I did not value myself and believed that asking for help would only confirm that I was a total failure. I kept trying to breakthrough, but often paralyzed by crushing anxiety and depression, I would lose whatever job I had, drop out of school, disappear from SGI-USA activities and become totally isolated. Knowing this, one of my young men’s leaders, Tony Geisler, drove five hours one way from Maryland to encourage me despite not even knowing if I was home. During the visit, Tony shared Ikeda Sensei’s profound conviction in the power of prayer and the mission that we have to fight for the happiness of others as the means to change our own suffering.

He also challenged me to help others, which was eye-opening, because I believed I had nothing to offer anyone. In desperation, I began chanting and studying Buddhism earnestly to help my own friends. Tony’s encouragement and his great act of friendship changed the course of my life and helped me to become the person I am today.

Though society had given up on me, my fellow SGI-USA members never did.

Since then, I completed my advanced degree in education and have taken on a role equivalent to a superintendent of a private school system in Los Angeles where, mystically, I support young people going through similar struggles as I experienced. And with the greatest appreciation for the support I received as a youth, I have helped four young men to start their practice over the past two years. I am resolved to continue to be their great ally in faith, while helping yet another youth stand up this year and awaken to their own great mission as a protagonist at this crucial time.

Embrace—Aki Ishii with women’s division members who supported her over the years, (l–r) Rita in 2004, Jo and Connie in 2008. Photos courtesy of Aki Ishii.

Aki Ishii

West Linn, Ore.

In the early 1990s, as a 16-year-old, I left Japan to spend a year as an exchange student in a small town in Georgia. I arrived with limited English skills, the only Asian student in a high school of 3,000, feeling completely out of place.

My host family, though perhaps well-intentioned, often said hurtful things to my friends and frequently fought with one another. I never truly felt safe in their home.

Around that time, during an economic downturn, Japanese companies had begun acquiring businesses, fueling resentment among people in the community. A particularly painful moment came when the school newspaper published an editorial filled with anti-Japanese sentiment, calling for us to “go home.”

It was then that I began chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, facing the wall for two hours a day, just wanting to be happy. I believe my mother’s daimoku from Japan also helped bring protection and support into my life.

One day, unexpectedly, my host father took me to a company party in a nearby town. In the living room, I saw a large Buddhist altar. That’s where I met a pioneer member who would become a life-changing presence for me.

She welcomed me like a daughter. Without ever pressuring me to practice, she supported me in countless ways—taking me to a Japanese grocery store, cooking familiar meals, and offering a listening ear when I was struggling and hurt. Her kindness was a lifeline.

By the end of the school year, things had changed. I had made friends, and they began standing up for me. One day, I was called into the principal’s office. There, the students who had written the editorial were made to apologize to me, one by one. I was given the opportunity to express how their words had made me feel. Even in my broken English, I believe my message got through.

After that year, I moved to Oregon to complete high school and attend college, then returned to Japan for work. Five years later, I came back to the U.S. to pursue graduate studies in Virginia, where I again found extraordinary support—this time from members of the SGI women’s division who met with me regularly to chant, study and navigate life together.

Years later, I went to an FNCC conference where I encountered a local leader from Georgia. When I asked about this pioneer, I learned that she had passed away. The leader connected me to her son, and I was able to convey how deeply grateful I still am for her compassion and care. What I remember most about her is that she was genuine. Her presence itself was so warm, and she would just envelop me with her big heart.

Looking back, throughout my youth, I was blessed with unwavering support from both the women’s and men’s divisions members. That support has shaped the person I am today.

Now, as a mother myself, I understand more than ever that it takes a village to raise even one child. We all share responsibility for nurturing the future.

In my district, I try to connect the grandchildren of a nearby family with my own so that they can grow up together in the garden of Soka. For me, kosen-rufu comes down to our community, our neighborhood, to the person right in front of us. That’s the youth we have to treasure.

May 9, 2025 World Tribune, pp. 6–7

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles