Installment 10 | Installment 20 | Installment 30 | Installment 40 | Installment 50 | Installment 60

Installment 1

History moves. Times change. The determination and actions of human beings make this happen.

On August 12, 1978, the Japan-China peace and friendship treaty was signed, setting in motion a new age of Japan-China relations.

At 12:30 p.m. on September 11, a 22-member Soka Gakkai delegation led by Shin’ichi Yamamoto, the fourth of its kind, arrived at Shanghai Hongqiao International Airport at the invitation of the China-Japan Friendship Association. Almost three and a half years had passed since Shin’ichi’s last visit [in April 1975].

As he stood on the steps leading down from the airplane, a refreshing breeze that hinted of autumn caressed his face. The trees in the distance shone a deep lustrous green.

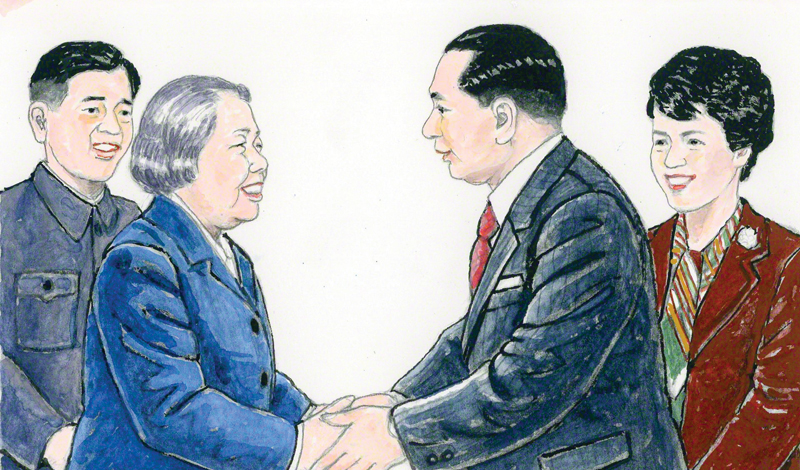

The smiles of the friendship association secretary general Sun Pinghua and others greeted Shin’ichi as he descended the steps.

“President Yamamoto! Welcome! Thank you for coming!”

Firmly shaking Sun’s outstretched hand, Shin’ichi said: “Thank you for the invitation and for taking the time to meet us at the airport.”

“I just arrived from Beijing 30 minutes ago myself,” Sun replied.

The secretary general was already an old friend, having forged a bond with Shin’ichi during his first visit to the country [in May 1974]. Given the rapidly warming mood of friendship between China and Japan, Sun must have been extremely busy. Nevertheless, he had traveled all the way to Shanghai to meet them. In part to repay this sincerity, Shin’ichi felt he had to make this visit to China a fruitful one for both nations.

The Japanese delegation divided among the 16 cars their Chinese hosts had arranged and headed for their accommodations at the Jin Jiang Hotel. As Shin’ichi took in the busy streets along the way, he thought: “Ten years have passed since I proposed normalizing diplomatic relations between Japan and China. The wheels of history have begun to turn significantly. Our political systems differ, but we are all human beings who wish for peace. We must build an enduring friendship!”

Installment 2

Shin’ichi reflected on the past decade.

On September 8, 1968, at the 11th Soka Gakkai Student Division General Meeting held at the Nihon University Auditorium in Ryogoku, Tokyo, he had discussed the issues between Japan and China and advocated three points to resolve them: (1) Japan’s recognition of the People’s Republic of China and the normalization of diplomatic relations with that country; (2) the restoration of China’s status in the United Nations, and (3) the promotion of bilateral economic and cultural exchange.

He said: “I hope that, when you become society’s leaders, the youth of Japan and China will be able to work together in harmony and friendship to build a bright new world. When all the peoples of Asia, with Japan and China leading the way, begin to assist and support one another, it will mark the start of an age when the dark clouds of poverty and the brutality of war now enveloping much of the region will lift and the sun of hope and happiness will at last shine its rays upon all of Asia.”

The proposal drew a huge reaction. Those who supported closer ties with China wholeheartedly applauded it, but an overwhelming majority fiercely condemned and attacked Shin’ichi.

Even at the Japan-US Security Consultative Committee three days later, a high-ranking Japanese foreign ministry official voiced his strong disapproval of Shin’ichi’s proposal.

Shin’ichi had been prepared for all this, however. He was determined to pierce the Cold War’s bedrock of mistrust and hatred and open the way to a better future for Asia and the world. Threats to his life were only to be expected. One cannot remain true to one’s beliefs without being prepared to risk one’s life.

In June 1969, Shin’ichi made a further appeal in the fifth volume of The Human Revolution being serialized in the Seikyo Shimbun: Japan should take the initiative to sign peace and friendship treaties with countries around the globe, placing priority on one with the People’s Republic of China.

Installment 3

Shin’ichi’s call for the normalization of diplomatic relations and the conclusion of a treaty of peace and friendship between Japan and China caught the attention of Chinese premier Zhou Enlai.

In addition, the respected Japanese political leader and Diet member Kenzo Matsumura, who had dedicated his life to improving Japan-China relations, urged Shin’ichi to visit China and meet with the premier, hoping his proposal would be actualized.

But Shin’ichi felt that restoring bilateral ties was fundamentally a political issue and that it would be inappropriate for him, a religious figure, to visit at that time. He suggested that representatives of the Komeito political party, which he had founded, do so instead.

When Matsumura visited China in the spring of 1970 to supervise negotiations for a Japan-China Memorandum Trade Agreement, he informed Premier Zhou about Shin’ichi and Komeito.

In June 1971, a Komeito delegation visited China and met with Premier Zhou, who laid out the necessary conditions for the normalization of bilateral relations. The Komeito delegation and the China-Japan Friendship Association drafted a joint statement incorporating those points and signed it on July 2. This opened the way for the normalization of relations. That joint statement, known as “Five Principles for Restoring Diplomatic Relations,” served as a guideline for later negotiations between both governments.

A short time later, in mid-July, US President Richard Nixon announced in a televised broadcast that he planned to visit the People’s Republic of China by May 1972. He also revealed that Henry Kissinger, his national security advisor, had already visited China and met with Premier Zhou. The course of history had begun a major shift.

Negotiations between Japan and China continued. Finally, on September 29, 1972, a joint Japan-China communiqué was signed in Beijing by Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka and Minister of Foreign Affairs Masayoshi Ohira and their Chinese counterparts, Premier Zhou Enlai and Minister of Foreign Affairs Ji Pengfei.

In addition to confirming the two countries’ desire to normalize relations, the communiqué included China’s renunciation of its demands for war reparations from Japan and both countries’ commitment to solidifying and developing friendly relations on the basis of the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence.[1]

Shin’ichi’s proposal had become a reality.

Speak out! Take action! From there, the wheels of change begin to turn.

Installment 4

The Japan-China Joint Communiqué also said that both countries would enter into negotiations toward concluding a peace and friendship treaty to solidify and develop peaceful, friendly relations. Once concluded, the treaty would be legally binding. Preliminary negotiations began in November 1974.

Shin’ichi met with Premier Zhou the following month, on December 5. Though seriously ill, the premier insisted on meeting Shin’ichi despite his physician’s objections.

“China-Japan friendship is our shared wish. Let’s work for this together,” the premier said. He added with vigor: “I hope that a peace and friendship treaty between our two countries can be signed as soon as possible.” His words touched Shin’ichi as if they were his last will. He felt the premier was entrusting him with his wish for long-lasting friendship between their nations. Shin’ichi vowed deeply, firmly, and powerfully to do everything he could as a private citizen to realize a Japan-China peace and friendship treaty.

In January 1975, during a visit to the US, Shin’ichi met with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. He asked the secretary what he thought about the proposed treaty and confirmed Kissinger’s support. Shin’ichi then communicated Kissinger’s thoughts to Japanese finance minister Masayoshi Ohira, who was also in the US at the time, when he met with him at the Japanese embassy.

Shin’ichi visited China a third time in April, meeting with Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping. They, too, exchanged views on the peace and friendship treaty.

The Japan-China Joint Communiqué stated that both nations would oppose efforts by any other country to establish hegemony in the Asia-Pacific region. However, some in Japan felt this provision, which was clearly directed against the Soviet Union, should be excluded from the treaty. They were concerned that it would antagonize the Soviet Union and thus harm Japan-Soviet relations.

Negotiations continued to face difficulties over the antihegemony issue. In fact, the Soviet Union had demanded that such a clause not be included.

During their meeting, Shin’ichi frankly asked Deng Xiaoping about China’s position on the antihegemony clause.

No matter how complicated a problem seems, we can find a solution if we have the courage to engage in candid and open dialogue.

Installment 5

During China’s Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping had been attacked as a “capitalist roader” (someone attempting to move the country in a capitalist direction) and removed from his post. He was even placed under house arrest. But Premier Zhou supported him behind the scenes and restored him to a central role in the government when the time was ripe.

Shin’ichi first met Deng, now vice premier, during his visit to China in December 1974, and met him again in April 1975. The head of the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s Asian Affairs Bureau was also present for the latter encounter.

Responding to Shin’ichi’s question about China’s position on the antihegemony clause, the vice premier noted that it was already included in the Japan-China Joint Communiqué. It was not directed only at the Soviet Union, he observed, but also at China, Japan, and any other nation or group seeking hegemony in the region.

When asked about relations between China and the Soviet Union, Deng said that the two nations’ peoples are maintaining good relations and that China was not worried about a Soviet invasion.

Shin’ichi asked forthright questions from various perspectives about the outstanding issues regarding the peace and friendship treaty, thus allowing him to confirm China’s position.

The following January, news of Premier Zhou’s death sent a shock wave around the world. Subsequently, the so-called Gang of Four, a group of Communist Party leaders led by Jiang Qing, attacked Deng Xiaoping and once again ousted him.

But that September, after the death of the party’s chairman, Mao Zedong, the Gang of Four were arrested, effectively marking the end of the Cultural Revolution.

The Cultural Revolution began in the mid-1960s as a class struggle in China. But it was also a power struggle that aimed to unseat key government figures such as Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping by denouncing them as capitalist roaders.

The Red Guards, groups of militant youth, spearheaded the Cultural Revolution. Seeking to eradicate old ways of thought, cultural traditions, and local customs, they focused their attacks on intellectuals and other “bourgeois elements,” and many people were killed.

Dogmatism and power struggles combined to create a calamitous period of strife and destruction.

Installment 6

In July 1977, Deng Xiaoping assumed the important posts of vice chairman of the Communist Party and vice premier of the State Council. And by 1978, China began to move in a new direction.

When the National People’s Congress convened in late February that year, it committed to the Four Modernizations—full-fledged efforts to develop agriculture, industry, defense, and science and technology—and announced that becoming a strong socialist state was the nation’s top priority. As part of the leadership reshuffle to take on these matters, Communist Party chairman Hua Guofeng was also appointed premier of the People’s Republic of China.

Concrete steps to conclude a Japan-China peace and friendship treaty got underway, but the path was not smooth for either nation. They had long remained at odds concerning the antihegemony clause, and resolving their differences proved challenging.

In April, more than 100 fishing ships flying the Chinese national flag approached, and some entered, the territorial waters of the disputed Senkaku Islands. The Japanese Coast Guard drove them from the area, but the fishermen insisted it was Chinese territory. Tensions grew.

The fishing boats finally left, however, and in the end the Senkaku Islands dispute did not seriously affect treaty negotiations.

On August 12, the Treaty of Peace and Friendship between Japan and the People’s Republic of China was at last signed in Beijing.

Consisting of a preamble and five articles, the first clause of Article 1 stated: “The Contracting Parties shall develop relations of perpetual peace and friendship between the two countries on the basis of the principles of mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit and peaceful co-existence.”[2]

The second clause of Article 1 read: “The Contracting Parties confirm that, in conformity with the foregoing principles and the principles of the Charter of the United Nations, they shall in their mutual relations settle all disputes by peaceful means and shall refrain from the use or threat of force.”[3]

Even if a peace and friendship treaty is signed, its success depends on continually cultivating a foundation of trust. A signed treaty is not the goal but the start of a long relationship of exchange.

Installment 7

The antihegemony clause that had been a sticking point was incorporated in Article II of the treaty: “The Contracting Parties declare that neither of them should seek hegemony in the Asia-Pacific region or in any other region and that each is opposed to efforts by any other country or group of countries to establish such hegemony.”[4]

The Chinese side had insisted that because the Japan-China Joint Communiqué included an antihegemony clause, the treaty should, too.

The Japanese side, however, was concerned that some would interpret this as an attempt by the two countries to keep the Soviet Union in check and would embroil Japan in Chinese-Soviet tensions. It therefore demanded that the treaty clarify that the antihegemony clause was not directed at any specific third country.

In the end, a commitment to antihegemony was included in the treaty as a general principle outlining the path forward for both Japan and China, with Article IV stating: “The present Treaty shall not affect the position of either Contracting Party regarding its relations with third countries.”[5] This was out of consideration for the Soviet Union.

After the treaty’s signing, its ratification was approved by the Japanese Diet [and formally ratified by the Cabinet] in October. Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping, Foreign Minister Huang Hua, and other Chinese officials then traveled to Japan to exchange the instruments of ratification, and the treaty went into effect [on October 23]. It was the first visit to Japan by top Chinese leaders since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China.

Shin’ichi was delighted that a peace and friendship treaty he had long advocated had finally been signed. He deeply vowed to do everything he could in his own capacity to ensure the treaty would endure in both letter and spirit.

A new age of Japan-China relations had arrived 10 years after Shin’ichi’s proposal calling for the normalization of diplomatic relations between the two countries.

The course of history can change. When people engage in sincere, openhearted dialogue, they can transform suspicion into trust, antagonism into friendship, and war into peace. That was Shin’ichi’s philosophy, his belief, his conviction.

Installment 8

Now [in September 1978], Shin’ichi was visiting China for the fourth time. It was nearly three and a half years since his last visit. He watched people walking along the streets as he traveled from Shanghai’s airport to his lodgings at the Jin Jiang Hotel.

Most women wore navy blue or khaki outfits, many with trousers. But some young women wore light pink or striped blouses. People looked cheerful and some even waved and smiled at Shin’ichi and the others as they drove by.

The Cultural Revolution, which harshly suppressed personal freedoms, had ended. Shin’ichi imagined that people felt renewed hope for China’s future as it embarked on achieving the Four Modernizations.

At the hotel, Shin’ichi and the Japanese delegation shared a convivial interlude with Sun Pinghua, secretary general of the China-Japan Friendship Association, and his colleagues. Shin’ichi introduced the members of his delegation. Among them were some Nichiren Shoshu priests and Soka University faculty visiting China for the first time.

Shin’ichi had hoped to bring High Priest Nittatsu on the trip, but the latter’s poor health precluded him from long-distance travel. Previously, the high priest had joined Shin’ichi on a number of overseas trips, including to Southeast Asia, India and other South Asian countries, the United States, Mexico, and Europe.

The westward transmission of Buddhism and worldwide kosen-rufu are the wish of Nichiren Daishonin, the Buddha of the Latter Day of the Law, and the mission his disciples must fulfill. Building world peace and eliminating misery from our world are the great mission of all practitioners of Nichiren Buddhism.

Though diplomatic relations had lapsed for a time, Japan owed China a great debt of gratitude as the country that had brought it Buddhism. Considering this history, Shin’ichi believed that wide-ranging cultural and friendship exchange was necessary for peace between the two countries.

To make the Buddhist principles of compassion and respect for the dignity of life the shared treasures of humanity, we must engage with leaders of various religions, including other Buddhist traditions. We need frank and open dialogues even with the leaders of communist countries, who view religion negatively.

Taking a closed-minded fundamentalist stance [that rejects dialogue with those of different beliefs] would distort the spirit of Nichiren Buddhism and cause us to lose sight of its essential purpose.

Installment 9

The Soka Gakkai delegation’s interpreter was Chow Chi Ying, a Hong Kong native and graduate student at Soka University.

When Shin’ichi visited Hong Kong in January 1974, Chow, then a first-year student, served as his Cantonese interpreter during meetings at Hong Kong University and the Chinese University of Hong Kong. His Japanese was still shaky, and he had a long way to go as an interpreter. But by giving him various opportunities, Shin’ichi hoped that he would grow into a first-rate interpreter.

Dialogues with world leaders aimed at realizing peace and prosperity for humanity require outstanding interpreters in many languages. Moreover, because Shin’ichi often discussed Buddhism, the interpreter needed a correct and deep understanding of Buddhist terms and concepts. Looking to the future, it would be vital to foster interpreters with a sound grasp of Buddhism who could convey Shin’ichi’s heart.

In Hong Kong in 1974, Shin’ichi told Chow Chi Ying that he would visit China soon and asked him to interpret for him then. Chow explained apologetically that he couldn’t interpret because the Cantonese spoken in Hong Kong differs completely in pronunciation from the Mandarin spoken in China.

Shin’ichi was well aware of this, of course. “That’s too bad … I’ll be meeting with China’s top leaders. I would have felt very comfortable if you were interpreting for me. I hope someday you will.”

Shin’ichi’s words pierced Chow’s heart. When he returned to Japan, he began studying Mandarin intensively, improving at an astonishing pace. He won a special prize at the first Soka University Chinese-language speech contest. When the university accepted government-sponsored students from China, Chow used his newly acquired Mandarin skills to interact and communicate with them.

On this, Shin’ichi’s fourth trip to China, Chow served as his Mandarin interpreter and did his very best.

When we awaken to our mission and have a seed of aspiration in our hearts, we will burn with a passion for learning, and the buds of our ability will quickly grow and blossom. Those with aspirations are strong.

Installment 10

During the informal gathering at the Jin Jiang Hotel, Shin’ichi smiled at Meng Bo, the Shanghai branch head of the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries. Two years earlier, Meng had visited Japan as deputy director of the Shanghai Jingju [Peking Opera] Theatre Company.

At that time, Shin’ichi had opportunities to meet with him at the Seikyo Shimbun building in Shinanomachi and Soka University in Hachioji. At Soka University, Shin’ichi watched the theater company’s performance in the school gymnasium. He also joined a gathering of some 50,000 youth on the athletic grounds to welcome the Chinese guests.

There, Shin’ichi shook hands with each theater member and spoke with Meng. In his speech at the gathering, Shin’ichi called for the early conclusion of the Japan-China peace and friendship treaty and resolved to put even greater effort into cultural and educational exchanges to make the golden bridge connecting the two countries shine eternally.

Now, two years later, Meng said: “I will never forget the welcome we received from 50,000 young people when we visited Japan the year before last. And how wonderful that the peace and friendship treaty you called for is becoming a reality. I am overwhelmed.”

Shin’ichi nodded and said with a smile: “Now is the time for us to create a strong current of genuine friendship. An age of friendship in the truest sense has arrived. Many young people who share my spirit follow in my footsteps. Let us create a great river of enduring friendship!”

Meng smiled. “You seem even younger than you were two years ago. You are so passionate.”

“Thank you for your kind words. Let us be young forever!”

Their lively conversation brought smiles all around.

Many of those present had become like old friends and acquaintances. It was hard to imagine that the Japanese delegation members had looked so tense on their first visit to China.

Relationships can completely change when we take time to get to know others, talk with them, and forge ties of friendship. To become friends is to connect heart to heart.

Installment 11

Shin’ichi and his group left the hotel and headed for a tour of the Shanghai Indoor Stadium. The modern round building boasted the latest facilities. It had seats for 18,000 people, which could be rearranged at the touch of a button.

The stadium’s director, Ma Fengling, showed them around.

“This is an impressive building,” Shin’ichi said. “Did you import any technology for its construction?”

“No. The technology, the facilities, everything is due to the efforts and unity of the Chinese people.”

“I sincerely admire the work of the great Chinese people. I can feel China’s dynamic progress toward the Four Modernizations.”

Shin’ichi believed that China would continue to develop remarkably.

Fast-paced modernization, however, would surely present challenges. And, as seen in Japan’s example, rapid development could have numerous adverse side effects, like pollution. He couldn’t help but pray sincerely that, for the sake of its more than 800 million citizens, China’s modernization would be a success.

After the tour, the group drove to the house where Sun Yat-sen (1866–1925), the father of modern China, spent his final years.

The large branches of the plane trees along the streets formed a tunnel of green.

In a corner of a residential area lined with buildings from the city’s French Concession era stood a Western-style building with a sign stating “Former Residence of Sun Zhongshan.” Zhongshan was another name by which the Chinese leader was known.

The residence displayed Sun Yat-sen’s desk, chair, books, and a photograph of his wife, Soong Ching-ling (1893–1981) [also a well-known Chinese political figure]. The books and other furnishings were just as they had been during his lifetime.

Mementos like these tell stories about when, where, and how they were used. As such, they are important links that help us remember the deceased and learn about their lives, actions, thoughts, and spirit. They are a bridge to a dialogue of the heart that transcends time and space.

Installment 12

As he stood in Sun Yat-sen’s former residence, Shin’ichi thought of the Chinese leader’s friendships with noted Japanese figures such as philosopher Toten Miyazaki (1871–1922) and film promoter and producer Shokichi Umeya (1868–1934).

Sun was born in 1866, during the Qing dynasty, in Xiangshan County (present-day Zhongshan City), Guangdong Province. He spent part of his teens in Honolulu, Hawaii, and returned to China to study medicine at the Hong Kong College of Medicine (present-day University of Hong Kong Faculty of Medicine). Around this time, he began to embrace revolutionary ideas.

He opened a medical practice in neighboring Macau, then a Portuguese territory, but focused his concern on his depleted and ailing homeland, where the Qing dynasty was on its last legs. The Qing government lost the Sino-French War (1884–85), a conflict with France over control of Vietnam, and then lost the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), exposing its weaknesses to Western powers. Also, under the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, many people lived in poverty.

Sun shed his white coat and picked up the scalpel of revolution. In 1894 in Hawaii, he formed a secret political society, the Revive China Society (Xingzhonghui), to overthrow the Qing dynasty and save his country by establishing a democratic state. He planned an uprising in Guangzhou, but it failed, and he fled to Japan. There he came to see the Meiji Restoration as a model for revolution in China.

Many Japanese, including Toten Miyazaki, spared no effort to help him—providing everything from housing to living expenses and financial support for his movement. As the Western powers successively encroached on Asia, Sun’s supporters sympathized with his ideal of building a new Asia. It was a bond of friendship and trust that transcended national and ethnic boundaries and was inspired by a grand vision. Solidarity based on high ideals forms a new force for creating a new age.

When Miyazaki first met Sun, he was disappointed because the Chinese leader didn’t appear very impressive to him. But as they spoke, his admiration grew. Upon reflection, Miyazaki wrote: “I had not emancipated myself from old-fashioned oriental standards of judging people by external considerations. Because of this weakness I often misjudge myself and, even more frequently, others.”[6]

Installment 13

The more Miyazaki came to know Sun Yat-sen, the more deeply he respected him.

In his autobiography, My Thirty-Three Year’s Dream, he wrote of Sun: “How noble his thought, how sharp his insight, how great his conception, how burning his fervor! How many persons like that have appeared among our countrymen? Truly, he is a precious jewel of Asia.”[7]

Later, Miyazaki traveled throughout East Asia in support of Sun’s revolution in China. There was nothing self-serving about his actions.

In his autobiography, he also described and praised Sun’s thought and character. Many Chinese students studying in Japan read the book, and it was translated into Chinese. It is said to have had a significant influence on the 1911 Revolution, which brought down the Qing dynasty and led to the establishment of the Republic of China (1912–49). Expressing his beliefs, Miyazaki wrote: “Ideals are to be carried out. If they cannot be carried out they remain dreams.”[8] Ideals are accompanied by action.

Shokichi Umeya was another of Sun’s financial supporters. He grew up in a family engaged in trade and rice milling in Nagasaki. As a boy, he moved to Shanghai, where he witnessed Westerners in the foreign concessions[9] discriminate against and humiliate the Chinese.

A decade or so later, Umeya opened a photography studio in Hong Kong. It was there he met Sun, who spoke passionately of the need to awaken his sleeping homeland, build a country that could stand up to Western powers, and save the people from misery.

Inspired, Umeya encouraged Sun to lead an uprising and promised to help finance it. He kept his word. He gained success as a film promoter and producer and generously used his wealth to fund Sun’s activities.

Sun Yat-sen led several uprisings, but they all failed. Gradually, however, the spirit of revolution spread throughout China. This ultimately gave rise to the 1911 Revolution and the birth of the country’s first republic.

Installment 14

The new government of the Republic of China was formed in Nanjing in January 1912, with Sun Yat-sen as its provisional president.

Yuan Shikai (1859–1916), prime minister of the Qing Imperial Cabinet, led peace negotiations with the new revolutionary government. After forcing the abdication of the infant Emperor Puyi (1906–67), he replaced Sun as provisional president of the Republic of China. With this, the Qing dynasty came to an end.

Yuan then began to persecute Sun and others. After officially assuming the presidency, he became more dictatorial. He tried to restore imperial government and proclaim himself the new emperor. China was moving in the exact opposite direction of Sun Yat-sen’s revolutionary ideals.

The French author Victor Hugo (1802–85) wrote: “To know how to distinguish the agitation arising from covetousness, from the agitation arising from principles, to fight the one and aid the other, in this lies the genius and the power of great revolutionary leaders.”[10]

A true revolution can be achieved only by overcoming human ego and self-interest—in other words, through human revolution.

In 1915, to expand its sphere of influence, Japan took advantage of the outbreak of World War I to press China with the so-called Twenty-One Demands. These included assenting to the transfer of Germany’s rights in Shandong to Japan, and extending the term for Japan’s concessions in South Manchuria. Yuan accepted these demands with some modifications, but Chinese sentiment toward Japan deteriorated.

Sun Yat-sen, residing in Japan at the time, was outraged. It was also during this period, with the help of Shokichi Umeya, that Sun and his wife Soong Ching-ling were married.

The following April, Sun left Tokyo to overthrow the Chinese government, but Yuan Shikai died of illness in June.

In 1917, Sun established the Military Government of Guangdong in Guangzhou. Conflicting loyalties within the new government, however, placed him in a difficult position, and he was forced again to seek refuge in Japan.

In the same year, the Russian Revolution took place, toppling the Romanov dynasty and establishing the Soviet Union as the world’s first communist state.

In January 1919, the Paris Peace Conference that followed World War I recognized most of Japan’s 21 demands to China, and Japan secured for itself Germany’s interests in Shandong.

Installment 15

The Republic of China’s near full acceptance of Japan’s 21 demands greatly humiliated the Chinese people. The flames of the anti-Japanese patriotic May Fourth Movement spread throughout the country.

The previous year, Japan, along with the United States, Britain, France, and other World War I allies, sent troops to Siberia to intervene in the Russian Revolution. While the other nations eventually withdrew, Japanese forces remained.

Japan’s military expansion into the Eurasian continent provoked anxiety in China, which perceived it as a threat.

In October 1919, Sun Yat-sen founded and headed the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang), championing the Three Principles of the People—nationalism, democracy, and people’s livelihood.

“Nationalism” in this context referred to the equality of China’s various ethnic groups and the country’s independence from foreign domination. “Democracy” established the sovereignty of the people. And “people’s livelihood” aimed to achieve social equality by rectifying economic inequalities.

Sun’s ideals were far-reaching, and he refused to let any difficulty or betrayal deter him. He had iron-clad convictions.

He declared: “If I believe in my heart that something is possible, then even if it is as difficult as moving mountains or filling in the sea, the day of success will ultimately come. If I believe in my heart that something is impossible, then even if it is as easy as snapping a twig with a flick of my wrist, the time of success will never come.”[11]

Great ideals are fulfilled by believing in yourself and deciding that you will achieve them without fail.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was founded in Shanghai in 1921.

In 1924, as he built friendly relations and partnerships with the Soviet Union, Sun Yat-sen reorganized the Nationalist Party and collaborated with the Communist Party to end military factions and imperialism. This was known as the First United Front. Then, that November, on his way from Guangzhou to Beijing, Sun visited Japan and gave a speech at the Hyogo Prefectural Kobe Girls School (present-day Hyogo Prefectural Kobe High School).

He asked whether Japan would be “the hawk of the Western civilization of Might or the tower of strength of the Orient.”[12] With every ounce of his energy, he admonished Japan against following the path of Western imperialism.

Installment 16

As he returned to Beijing, Sun Yat-sen was already gravely ill. He died there in March 1925 at age 58.

Among his last words were: “The revolution has not yet succeeded.”[13] Continuing to fight evil is the path of revolution.

After Sun’s death, Chiang Kai-shek (1887–1975) of the right-wing faction of the Nationalist Party became commander-in-chief of the National Revolutionary Army. He adopted an aggressive stance toward the Communist Party and established the National Government of the Republic of China (1925–48) in Nanjing. The First United Front collapsed.

Sun’s wife, Soong Ching-ling, was elected to the Nationalist Party Central Executive Committee after her husband’s death. Her younger sister, Soong Mei-ling (1897–2003), was married to Chiang Kai-shek. But Soong Ching-ling opposed Chiang Kai-shek’s approach, advocating instead that the Nationalist Party should remain faithful to Sun’s position of cooperating with the Soviet Union and accepting communism.

In 1931, the Manchurian Incident occurred.

Soong Ching-ling insisted that the Nationalist Party and the Communist Party should unite to fight Japan. The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) thus led to the creation of the Second United Front. After the war, however, tensions between the two parties intensified, and China descended into civil war. The Communist Party defeated the Nationalist Party, and Chiang Kai-shek fled to Taiwan.

Soong Ching-ling found a way to carry on Sun’s aspirations in the Communist Party. In 1949, after the birth of the People’s Republic of China, she supported the new China, serving dually as vice chairperson of the state and vice chairperson of the Central People’s Government.

At the time of Shin’ichi’s fourth visit to China, Soong was already 85. Still, as vice chairperson of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC), she actively represented her country.

On the evening of September 11, while touring Sun Yat-sen’s former residence, Shin’ichi said to those traveling with him: “Why was the National Party defeated by the Communist Party? I think there were many factors, but first, they failed to win the people’s support. Corruption was rife among the National Party leaders, who sought to enrich themselves. People lost faith and turned away from the party. It is the people who embody the ideals of a revolution. What matters is how a person lives.”

Installment 17

Shin’ichi and the others entered the courtyard, where they found a lush green lawn and luxuriant trees. They sat on the grass and enjoyed an informal discussion.

Looking at the young people, Shin’ichi said: “Sun Yat-sen grounded his way of life in the traditional Chinese philosophy of the Way of Heaven. For example, he believed that oppressing people is going against Heaven and that resisting it is acting in accord with Heaven. Sun built his revolution on his belief in this philosophy. In so doing, he found the strength to discipline himself and overcome adversity.

“Without a foundational principle, even a movement with lofty ideals will be undermined by greed and ambition and ultimately fail. No revolution can truly succeed without human revolution.”

Sun Yat-sen wrote: “Where do we begin the task of revolution? We must start from within ourselves, eliminating negative thoughts, habits, and tendencies, our brutal, corrupt natures, our inhumane and immoral qualities.”[14]

He also wrote: “But we have already decided we are responsible for China’s reform and development. No matter what may happen, we must never let that spirit perish as long as we live. We must not be discouraged when we fail or retreat in the face of difficulties. We will put our heart and soul into our work and go forward with courage and energy in accord with the tide of world progress and the divine principle that good must flourish and evil perish. Then we will succeed in the end.”[15]

This is exactly the conviction and way of life of Soka Gakkai members, who have stood up to realize world peace and human happiness based on the fundamental Law of life—in other words, to accomplish the mission of kosen-rufu.

Our lives shine in the truest sense when we transcend petty stories of seeking personal gain and success and instead write epic stories of contributing to people’s happiness and bettering the world.

Installment 18

Upon returning to their hotel, Shin’ichi and his party attended a welcome banquet hosted by Shanghai City representatives.

In his short speech, Shin’ichi expressed his deep appreciation to Sun Pinghua, secretary-general of the China-Japan Friendship Association, for making the long journey from Beijing. He also conveyed his joy at being able to visit China on this historic occasion of the conclusion of the Japan-China Peace and Friendship Treaty. He voiced his heartfelt determination: “I am resolved to make this visit a substantive first step to ensure that the golden bridge of Japan-China friendship in this new phase will endure forever.”

He noted that Soka University, which the Shanghai Jingju [Peking Opera] Theatre Company had visited in June 1976, was hosting exchange students who would shoulder China’s future. He also shared that a Zhou Cherry Tree had been planted on the Soka University campus in honor of the Chinese premier Zhou Enlai.

He said: “If Premier Zhou were still with us, he would no doubt be delighted by the peace and friendship treaty, which has finally been signed. But our goal of building lasting peace and friendship between our two nations has yet to be realized.

“The saying ‘pie in the sky’ refers to an idea that is nice in conception but unlikely to come to fruition. Though signed, this treaty will be nothing but a piece of paper—pie in the sky—if we fail to make it a living reality, forgetting the hard work of all those involved. We mustn’t allow that to happen.

“We know that friendship between China and Japan is vital to realizing peace in Asia and the world. To usher in a new age, to make a fresh start, I will strive with all my sincerity and strength to create a current of bilateral friendship that will endure for generations to come.”

Shin’ichi wanted to foster mutual understanding and trust and bring hearts together through cultural and educational exchange. He believed this was key to building the foundation for lasting peace.

Installment 19

On September 12, the next day, the Soka Gakkai delegation had breakfast with Sun Pinghua and others at the Jin Jiang Hotel.

Shin’ichi and his wife, Mineko, sat at a round table with Sun. A Japanese breakfast of mezashi (grilled dried sardines), the cold tofu dish hiyayakko, and miso soup was laid out before their host.

Sun exclaimed in surprise: “Oh! Mezashi! And hiyayakko! And miso soup!”

Mineko smiled and said: “When we last visited China, you said you had studied in Japan and could never forget the taste of dried sardines and tofu.”

“You have been so kind to us since our first visit to China,” Shin’ichi added, “and we discussed how to show our appreciation. We remembered you mentioning you had enjoyed Japanese food as an exchange student, so we decided to bring the ingredients from Japan. My wife prepared it for you.”

“I hope you like it,” Mineko said.

Shin’ichi and Mineko had discussed whether they could even bring in the ingredients and how to transport the tofu in one piece.

“Please eat before it gets cold.”

At Mineko’s urging, Sun picked up his chopsticks and, with a beaming smile, took a bite of the sardines.

“It brings back memories! Delicious! I can truly feel your sincerity.”

“We’re happy to see you enjoying it so much,” Shin’ichi said with a grin.

It was a small gesture, but it came from the heart. Sincere interactions are the essence of friendship.

Installment 20

Sun Pinghua was born in 1917 in Fengtian Province (present-day Liaoning Province) in northeast China, which 15 years later became part of Japan’s puppet state of Manchukuo.

Sun graduated with honors from an advanced middle school, which was equivalent to a Japanese high school. But instead of going to university, he took a job at the customs department of the Manchukuo Ministry of Economics tax bureau. He wanted to start earning a salary quickly to repay his mother for everything she had done for him.

The Japanese, however, held the real power at his workplace. He had no university degree and was only a low-level public servant, so he saw little hope for the future. During this depressing time, a friend suggested he go study in Japan. Much to his surprise, he passed the exchange student examination. He then moved to Japan in 1939 at age 21.

He first enrolled in the Tokyo Institute of Technology’s preparatory school and later entered its applied chemistry department.

After four and a half years of study in Japan, Sun returned to China during the Pacific War in the summer of 1943. That marked the end of his university studies.

He joined the Communist Party and became active in the party’s wartime underground resistance activities while working at a bank in Harbin. The war ended, and the struggle between the Communist Party and the Nationalist Party intensified. Most people supported the Communist Party, and in October 1949, the People’s Republic of China was established.

With his experience studying in Japan, Sun Pinghua was assigned the job of looking after Japanese visitors. Thus began his involvement in China-Japan friendship.

He later served as president of the China-Japan Friendship Association and wrote of his feelings: “I have always believed that the most important factor in amicable relations between China and Japan is personal relationships. Friendship based on heart-to-heart bonds is crucial.”[16] These are the words of a person dedicated to promoting friendship with Japan since the birth of the new China. Friendship without sincerity cannot bear fruit.

Installment 21

After breakfast, Shin’ichi and his party visited the Zhouxi People’s Commune,[17] about 9 miles from central Shanghai. When they arrived, they were welcomed by commune residents beating gongs and drums and children waving balloons and flowers.

“They all know of your dedication to China-Japan friendship,” Sun Pinghua said to Shin’ichi.

The commune comprised about 5,000 households, around 18,000 people. White cotton fields, vegetable plots, and green rice paddies stretched out all around. The party was given a tour of the commune, including its irrigation facilities, a garment factory, an agricultural machinery plant, and a hospital.

Everyone was working joyfully for modernization. Particularly noticeable was the number of young women. Even at the factory that made parts for tractors and other agricultural equipment, they worked energetically alongside their male colleagues. According to a commune representative, women were joining the workforce all over China, from trolleybus drivers in Shanghai to air force pilots.

Looking to the future, Shin’ichi believed that women’s increasing participation in society was an unstoppable trend. For Japan, too, making the most of women’s skills in every sphere of endeavor was a critical issue. To that end, it would be essential to create a supportive working environment for women, including establishing the necessary policies and institutional structures. The first fundamental step would be to change men’s attitudes. The time had come to alter old ways of thinking, such as the assumption that a woman’s place is in the home doing housework and raising children.

Lifestyles change drastically over time. Human beings have no choice but to live with continual change. Therefore, to live well, one must develop the capacity to cope with change, rather than cling to one’s set ideas or past experiences.

Installment 22

Large red and white posters with slogans hung throughout the commune. One read: “Long Live the Great Unity of the World’s People!”—the same slogan that had greeted Shin’ichi and the others at Shanghai Airport.

“Let’s Start a New Long March with Premier Hua Guofeng!” also caught Shin’ichi’s attention. With the end of the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese people viewed the Four Modernizations they had embarked on together with Premier Hua as a new Long March.[18]

Shin’ichi asked a young man working at the commune: “What does ‘a new Long March’ mean to you?”

The young man replied without hesitation: “It means supporting modernization through our work here at the commune. We work, strive, and use our creativity to improve and enrich people’s lives.

“Our generation couldn’t take part in the original Long March. But now we are in a struggle to serve the people, replacing weapons with tools. That’s the spirit of this Long March, I think.”

His eyes sparkled.

“Your determination is wonderful. You have such a noble heart. I’m impressed. The future rests on the shoulders of youth. I wish you the best of luck.”

Shin’ichi then said to his traveling companions: “China is going to make great progress. The youth are serious. You can feel their commitment to modernization.”

If you want to know about a country’s future, talk to its young people. Are they determined to serve others and society? Are they passionate about improving themselves? Are they working hard? The answers will tell you everything.

That afternoon, the delegation visited the Shanghai Children’s Palace in Yangpu District. They learned that every district of Shanghai had one of these activity centers for children.

Installment 23

Children waving bandanas and flowers greeted the Soka Gakkai delegation with a hearty “Welcome!” in Chinese.

“Xie xie! (Thank you!)” Shin’ichi replied as he and the others waved back enthusiastically.

“I’m so happy to meet young friends today,” he said, shaking hands with each child.

A boy and a girl, both 11, stepped forward and said to Shin’ichi and Mineko: “We wholeheartedly welcome all of you. We’ll be your guides today.”

They were self-assured, confident, and composed.

“Thank you,” Shin’ichi said to the girl. “Please give my best to your parents.”

“I will! How many children do you have?” she asked him.

Shin’ichi replied playfully: “Three, all boys. With only boys, I’ve always wanted a daughter. Can I think of you as my daughter?”

“Of course.”

“Well, then, I’ll have to say hello to your parents. Where does your family live?”

“Near here.”

“I see. But I’m sorry to say I don’t have time to visit them today.”

The girl smiled. “You’ll come back to Shanghai, again, won’t you? You can visit us then.”

“I will. And I hope you will come to Japan in the future, too. I’ll give you a warm welcome.”

“When I grow up, I’ll definitely go to Japan.”

“Wonderful. I’ll be waiting!”

Natural conversation and heart-to-heart interaction foster friendship. Shin’ichi was determined to sow seeds of friendship in the children’s hearts, for he knew that eventually those seeds would flower and bear fruit.

Installment 24

The Children’s Palace director told the visitors: “We provide after-school instruction in arts and literature, sports, technology, crafts, and music. Currently, about 1,000 children use the facility each day.”

Shin’ichi and the others were led on a tour of the center, including rooms set aside for chorus, violin, folk instrument, harmonica, dance, and table tennis instruction. They were impressed to see the children practicing earnestly under their teachers’ guidance.

In the chorus room, the children performed “Soran Bushi,” a popular fisherman’s folk song from Hokkaido. “Yaren soran soran,” they sang. Shin’ichi called out “Hai, hai,” a traditional interjection, and clapped in time as his party followed suit. Everyone’s hearts instantly became one.

All forms of art and culture—whether music and song, dance, painting, sports, or cooking—transcend ethnic, ideological, and national boundaries and connect people’s hearts, bringing them together.

When the chorus finished, Shin’ichi said: “Xie xie, xie xie! (Thank you, thank you!) That was very good—the best gift for us from Japan.”

The group played table tennis with some of the children and were also treated to a martial arts demonstration.

To commemorate the occasion, Shin’ichi gave the children traditional Japanese toys—such as spinning tops, kendama,[19]and paper balloons—as well as paintings by students of the Soka schools. The children’s beaming smiles conveyed their joy at receiving these gifts of sincerity and friendship.

In turn, they presented the visitors with traditional Chinese cutout pictures, ink paintings, calligraphy, and woodblock prints.

“Thank you so much for today,” Shin’ichi said. “I will tell the children in Japan about you. When you grow up, please come visit us!”

Everyone then took a group photo.

The stream of friendship must become a great river that flows into the future for generations to come. Shin’ichi resolved to do everything he could to ensure that this would not be a fleeting exchange.

Installment 25

That evening, Shin’ichi and his party were invited to see a performance by a Shanghai acrobatics troupe, one of many renowned for their exquisite skill.

The audience was thrilled by the challenging and superb performances, including plate spinning on numerous poles and dancing with large fans balanced on foreheads.

Shin’ichi cherished a hope to one day invite, through the Min-On Concert Association, a Shanghai acrobatic troupe to perform in Japan as a symbol of friendship.

The next morning, September 13, Shin’ichi visited Fudan University in his capacity as Soka University founder. His purpose was to present books as part of an educational exchange program, as he had done in 1975.

When Shin’ichi and his group arrived in front of the Physics Building, the site of the presentation ceremony, faculty and students greeted them with loud applause.

The diminutive Su Buqing, the university’s president, stood smiling in the entryway, wearing a traditional Mao suit. His deeply lined face reflected his long years of hard work. Though it was their first meeting, his warm expression made Shin’ichi feel like they were old friends.

“Welcome to Fudan University. I’ve been looking forward to meeting you.”

The president held out his hand, and Shin’ichi firmly grasped it, saying: “Thank you for your kindness. I am delighted to meet you.”

President Su, an internationally acclaimed authority in differential geometry, had studied in Japan for 12 years from 1919. After graduating from Tokyo Higher Technical School (present-day Tokyo Institute of Technology), he pursued postgraduate studies at the Mathematical Institute of Tohoku Imperial University (present-day Tohoku University), earning his doctorate in science. He was one of the founders of modern Chinese mathematics.

During the Cultural Revolution, his renown resulted in him being denounced as “bourgeois” and “counterrevolutionary.” When that storm eventually subsided, he became Fudan University president in 1978.

The French thinker Voltaire said: “Truth always prevails over persecution.”[20] Shin’ichi felt that China had a bright future.

Installment 26

Shin’ichi had heard that President Su would soon be 76. But his straight posture and hearty appearance belied his age.

The presentation ceremony took place in a conference room in the Physics Building. In addition to the university president, the vice president, the head of the library, faculty and staff from the economics and history departments, and student representatives attended.

In his remarks, Shin’ichi expressed joy at visiting the university again and gratitude for the warm welcome. Noting that his fourth visit to China coincided with the signing of the Japan-China Peace and Friendship Treaty, he said he burned with fresh determination for the future.

He then shared his thoughts regarding the book presentation. “As a token of our sincerity, we are gifting 1,000 specialized books on natural science and other subjects. We hope they may be of some small help as China pursues the Four Modernizations.”

Shin’ichi then reflected on the history of Japan-China relations. “Our countries have experienced painful periods of war with each other. But travel to one another’s countries by our peoples in times of peace has contributed significantly to the development of both our cultures. Centuries ago, Japanese envoys to the Sui and Tang dynasties learned from your advanced culture. More recently, in the early 20th century, your great leader Zhou Enlai and many others from China have studied in Japan.

“The warm relationship between the Chinese writer Lu Xun (1881–1936), who studied at Sendai Medical College (present-day Tohoku University School of Medicine) in 1904, and anatomy professor Genkuro Fujino (1874–1945) symbolizes friendship that transcends national borders.

“I have heard that President Su also studied at Tohoku University in Sendai. Such educational exchange has enriched both our cultures and has been a major force in building a brighter future.”

Exchange between universities is extremely important for cultivating enduring friendships. Even if Japan-China relations are strained in the world of politics and diplomacy, educational and academic exchange can foster mutual understanding and stronger ties of friendship between Japanese youth and the young future leaders of China.

Installment 27

Shin’ichi next touched on how students from China were studying hard at Soka University, which he founded with the wish that it would serve as “a fortress for the peace of humankind.”[21] He also reported that a Zhou Cherry Tree had been planted on the campus in honor of the Chinese premier Zhou Enlai.

He added that two new female students from China began studying at the university in April. “I am convinced that such steady, grassroots exchange will forge bonds of friendship and trust in the hearts of everyone involved,” he said, “and that this will bring beautiful flowers of friendship to bloom in the future. I am determined to persevere steadily on the path of cultural and educational exchange, even if our present efforts go unnoticed.

“Education, in particular, is most important since it determines a nation’s future. Expanding educational exchange—through which we can learn about and emulate each other’s outstanding qualities—will become increasingly important. I hope we can continue to work together in this area.”

The audience applauded.

When Shin’ichi finished speaking, he handed President Su a catalog of the 1,000 books being presented, as well as a few of those books. Once more applause filled the room.

President Su then spoke. He welcomed the visiting delegation and said with great emotion: “I deeply value your tireless efforts to protect and develop the friendship between the people of China and Japan. I am especially moved by President Yamamoto’s consistent support for the signing of a China-Japan peace and friendship treaty.”

Tears welled in President Su’s eyes.

He had spent the impressionable years of his youth living and studying in Japan. Doubtless, he had made many Japanese friends and formed bonds that transcended the antagonism and conflict caused by war between their countries. True peace and friendship can be achieved only when the roots of friendship spread far and wide in the earth of people’s hearts.

Installment 28

President Su shared his conviction that the treaty would promote amicable relations between the two neighbors for generations and add a brilliant new chapter in their history.

Touching on the book presentation, he said that the current gift and the more than 2,000 books the Soka Gakkai presented in 1975 would contribute significantly to the university’s teaching and research in science and the humanities.

“I firmly believe that with the China-Japan Peace and Friendship Treaty as a new starting point,” he continued, “the flowers of cultural exchange that the people of both countries have so carefully nurtured will bear even richer fruits of friendship. Let’s join hands and strive to write a new chapter in peaceful and friendly China-Japan relations!”

Enthusiastic applause filled the room.

An informal discussion followed. President Su, who had lived and studied in Japan for 12 years, replied in fluent Japanese to the Soka Gakkai delegation’s questions.

He explained that all students at Fudan University lived in dormitories, with six or seven students to a room enjoying their studies together. The students present said it was the perfect learning environment, which included a fully equipped library, free housing and utilities, and access to medical care when ill. The students’ words conveyed their trust and appreciation for their country. Such trust, Shin’ichi thought, was an essential foundation for the nation. If a nation loses the trust of its people, its foundation will crumble. With the Cultural Revolution led by the Gang of Four behind them, the Chinese now seemed to have high expectations for and trust in the state and the Communist Party.

The conversation turned to the Japanese-language program at Fudan University, and President Su introduced the faculty. “As a matter of fact, my son is one of the instructors. He is planning to go to Japan soon.”

“How wonderful!” Shin’ichi said. “Both father and son will have lived in Japan and served as bridges of friendship between our two nations.” President Su smiled.

Installment 29

That afternoon, the group took an express train from Shanghai to Suzhou.

They had planned to go directly from Shanghai to Wuxi, but their Chinese hosts wished to give them a tour of the scenic Jiangnan area in which Suzhou lies. There was even a famous saying: “Above there is heaven, below there is Suzhou and Hangzhou.” The group decided to spend a night in Suzhou.

On the train, the delegation discussed their impressions of Shanghai, which they had visited three and a half years earlier. New things they noticed, such as women with perms on the street, became topics of conversation.

“China is changing,” a woman in their group said. “The women’s faces are vibrant. You can feel their joy at their freedom and eagerness to shoulder a new age. I’m sure China is going to develop quickly.”

Shin’ichi spoke with Sun Pinghua, the China-Japan Friendship Association secretary-general, about the essence of friendship. On Shin’ichi’s first visit to China four years earlier, the two had exchanged ideas on ensuring lasting friendship between the two countries. Shin’ichi had never forgotten what Sun had said about a passage from Lu Xun’s short story “My Old Home”: “Lu Xun wrote, ‘Actually the earth had no roads to begin with, but when many [people] pass one way, a road is made.’[22] I feel that is how the path of friendship is created—by many people taking step after step as they come and go. This ongoing process forms a great road to peace. It can’t happen overnight.”

Shin’ichi had replied: “I agree completely. My wife and I will visit China many more times in the future. And not only us. We will bring many young people as well. Let’s create a road together for peace, friendship, and the future.”

Sun also clearly remembered that conversation.

“You have lived true to your words and continue to build a fine road. I am very grateful.”

The two men shook hands again.

Installment 30

The tranquil countryside rolled by endlessly as the train made its way to Suzhou. Green rice plants—perhaps the second crop—swayed in the breeze. Here and there, children rode on water buffalo. Small boats with white sails stirred gentle waves on the canals crisscrossing the land.

The Soka Gakkai delegation arrived in Suzhou, renowned as a city of water, shortly after 3 p.m. The trip from Shanghai had taken about 90 minutes.

Suzhou is also known as a city of gardens. A saying goes: “The gardens of Jiangnan are the best in the world, and the gardens of Suzhou are the best in Jiangnan.” The city had once boasted more than 200 gardens.

Their hosts took the group to one of China’s four most famous gardens, the Humble Administrator’s Garden (Zhuozheng Yuan). Built in the early 16th century, during the Ming dynasty, it covers more than 5 hectares (12 acres) and features an exquisite arrangement of ponds and waterways of various sizes, artificial hills, winding corridors, and pavilions. It was like viewing a masterpiece.

They also visited the Hanshan Temple, which the Tang-dynasty poet Zhang Ji immortalized in his poem “Night Mooring at Maple Bridge.”

That evening, the group was treated to a welcome banquet.

The consideration of their Chinese hosts was evident everywhere throughout their visit, including this side trip to Suzhou.

For example, with few automobiles in China at the time, most people rode bicycles. But in both Shanghai and Suzhou, the Chinese hosts provided cars for every delegation member or two, rather than one bus for all.

When one of the members mentioned this, Sun Pinghua said emphatically: “That is because we are well aware of the incredible commitment with which President Yamamoto and the Soka Gakkai have opened the way for China-Japan friendship and what an important and historic contribution it is. President Yamamoto has been indispensable in normalizing China-Japan relations and signing the recent peace and friendship treaty. We will never forget your sincerity and the debt we owe you.”

Creating a garden of friendship and peace begins with tilling the soil of trust with sincerity and commitment.

Installment 31

On September 14, the delegation toured the Suzhou Embroidery Research Institute to observe the process of producing Suzhou embroidery, which has a history dating back more than a thousand years.

In the first room was an embroidered six-panel folding screen 6.5 feet high. The screen’s beautiful design and vivid colors, depicting plum blossoms, camellias, bamboo, and birds, captivated the group. Astonishingly, the reverse side bore the same design.

As Shin’ichi watched the embroiderers at work, admiring the highly refined and detailed technique, one of the institute’s staff explained: “Suzhou embroidery has traditionally been handed down as a domestic handicraft. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, this institute was established to improve techniques and train successors. As a result, we now use 1,000 types of thread, and the number of embroidery techniques has increased from 18 to 50.

“Also, during the Cultural Revolution, designs were standardized, mainly focusing on images of laborers at work. However, we can now depict many things, including scenic views like the Great Wall of China and flora and fauna.”

He was clearly happy that the Cultural Revolution had ended and a new breeze of freedom was blowing.

Without freedom, there is no human happiness. But to attain freedom and establish happiness, each individual must exercise self-discipline and strive for self-improvement. In other words, we need the philosophy of human revolution. Shin’ichi believed that this would be an important focus for the future.

After the research institute, the group visited the famous landmark Tiger Hill in the city’s northwest.

The hill’s name originates from the legend of a white tiger said to have crouched atop it three days after King Helu of Wu was buried there in China’s Spring and Autumn period, some 2,500 years ago.

Atop the 98-foot hill stands the Tiger Hill Pagoda (also known as the Yunyan Pagoda), an octagonal, seven-story brick structure. Completed in 961, it rises nearly 157 feet. The pagoda leans about three degrees because of its uneven foundation, earning it the nickname the “Leaning Tower of China.”

Installment 32

The delegation took a group photo with the Tiger Hill Pagoda soaring in the background and spent time talking with Suzhou City representatives at the rest area below.

“I wish to show my gratitude to you all by sharing a song I wrote,” Shin’ichi said. “I composed the lyrics for our members in Japan’s Chugoku region,[23] but I have revised them and had them translated into Chinese. I’ve also retitled it ‘Song of Beloved China,’ and I offer it to you as a token of our friendship.

“I hope you will sing along.”

Lyric sheets were handed out. Chow Chi Ying, the group’s interpreter, sang to the music playing from the delegation’s cassette player.

The people from Suzhou began singing too, but having heard the song only once, their voices faltered. The delegation then joined in, in Chinese. Afterward, they sang it in Japanese:

China, resounding with joy,

setting sail spiritedly toward peace.

Ah, dear friends, hearts burning, burning crimson.

Let’s leap forward, hand in hand …

When they finished, everyone applauded and gave kudos to one another. One Suzhou representative praised the lyrics, saying they conveyed Shin’ichi’s feelings toward China. Another said the song was easy to learn and that they had already memorized it.

Shin’ichi smiled.

“Thank you. We will think of you whenever we sing this song. One of the great benefits of this visit is making so many new friends in Suzhou. I am so happy.”

Songs bring people together. The joy, hope, love, friendship, and wish for peace they convey are common to all humanity. Therefore, they strike a powerful chord in our hearts as fellow human beings.

Installment 33

At 3 p.m. on September 14, the delegation took a train from Suzhou to Wuxi, arriving in around 50 minutes.

They enjoyed friendly conversations with Wuxi City representatives while touring Lake Tai, one of China’s four great lakes.

The next day, September 15, they visited the Yixing Redware Crafts Factory in Yixing, Jiangsu Province, an area renowned for its pottery. They also visited the Shanjuan Cave, a limestone cave formed 1.5 million years ago.

Wherever they went, Shin’ichi and the others built bridges of dialogue. Just before 4 p.m., they boarded a train from Wuxi to Nanjing, and soon a beautiful sunset greeted them.

About 20 minutes before they arrived, a young Japanese man approached Shin’ichi. “You’re President Yamamoto of the Soka Gakkai, aren’t you?”

“Yes, that’s right . . . .”

He introduced himself, mentioning first that he wasn’t a Soka Gakkai member. He explained that he worked for a shipping company in Tokyo and was in China for training.

Seeming to muster his courage, he continued: “Actually, I’d like to ask you a favor. A young woman in my office in Japan is a devoted Soka Gakkai member. She’s getting married today. Seeing you, I decided to come over and ask if I might trouble you to write her a congratulatory message.”

“Is that so? Is that why you came over to me? Thank you! Let me write her a poem then.”

The young man handed Shin’ichi a notebook.

Shin’ichi swiftly wrote:

I pray

on my journey in China

for the happiness of you both.

Seeing how delighted the young man was for his colleague, Shin’ichi sensed that the young women’s division member had earned the trust of her coworkers, which made him happy. Expanding circles of trust leads to expanding kosen-rufu.

“Please give my very best to your friend.”

Shin’ichi chanted in his heart for the lasting happiness and health of the newlyweds.

Installment 34

The Soka Gakkai delegation arrived in Nanjing just after 6:30 p.m.

A large contingent of Jiangsu Province representatives welcomed them at the station with warm smiles.

Nanjing, the capital of Jiangsu Province, is one of China’s ancient capital cities. It also served as the seat of the provisional government of the Republic of China [in the wake of the Chinese Revolution of 1911–12], and later became the capital of the Nationalist government [in 1928].

In 1937, during the Sino-Japanese War, Japanese forces invaded Nanjing, creating horrific devastation.

Shin’ichi’s heart ached when he thought of the many precious lives lost here.

At that night’s welcome banquet at the Nanjing Hotel, he spoke of the destruction inflicted on Nanjing during that war and the tragic loss of so many Chinese lives.

“The Soka Gakkai is a people’s organization dedicated to promoting peace and culture. Because of oppression by the tyrannical militarist authorities, our founding president, Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, died in prison for his beliefs, and our second president, Josei Toda, was persecuted and imprisoned for two years. Militarism inflicted enormous harm and loss of life on the people of your nation, and we of the Soka Gakkai, too, experienced oppression under its high-handed authority.

“That is why I have devoted myself to working for peace and friendship between Japan and China with the conviction that we must never permit militarism to cause such devastation again and that we must build lasting peace for humanity.

“We offer our deepest condolences and prayers to all the victims of the Sino-Japanese War and will convey to the Japanese people how Nanjing has arisen from tragedy and rebuilt itself into a wonderful city.”

Shin’ichi felt it profoundly significant to be visiting China now that a peace and friendship treaty had been signed and to be standing here in Nanjing, the site of the Sino-Japanese War’s most tragic events.

“From now, Japan and China will move together for peace,” he thought. “We must make Nanjing the starting point of this new endeavor. Because of the horrific events that took place here, Nanjing must become a great center for peace and friendship. Squarely facing the past and using it as a force to build the future—this is the mission of those living today.”

Installment 35

September 16, the day after they arrived in Nanjing, dawned to beautiful sunny skies. Around 10 a.m., Shin’ichi and the delegation visited the Yuhuatai Memorial Park of Revolutionary Martyrs.

A famous legend about Yuhuatai says that at the beginning of the sixth century, a Buddhist priest was reciting a sutra on a hill when flowers rained down from the sky. Hence the name Yuhuatai, which means “Terrace of Raining Flowers.”

The trees were dazzlingly green in the sunlight. Belying its beautiful name, Yuhuatai is where many brave martyrs who risked their lives to build a new China were executed for resisting the Nationalist Party government in Nanjing.

The head of the memorial park explained the gruesome history.

“By the time the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, more than 100,000 martyrs had been executed here.

“And in 1937, a horrific tragedy occurred when Japanese troops invaded Nanjing, killing untold numbers. The city was also burned down. For the Chinese, Yuhuatai is an unforgettable place stained with the blood of the people.

“But this was the work of a group of militarists and had nothing to do with the Japanese people. And while China certainly suffered a terrible loss of life, the war also brought great tragedy to the Japanese people.

“Although our two countries experienced an unfortunate period of war, when viewed from our two-millennia history of cultural exchange, it was only a fleeting moment. Since our countries have signed a peace and friendship treaty, I am confident that if we continue to make efforts to deepen trust, we will be able to enjoy friendly relations for generations to come.”

He spoke with calm assurance.

Shin’ichi pondered deeply: “Without averting our eyes from this history, now is the time to open the path to lasting peace and friendship between Japan and China. This is the way to honor the memory of the victims who died so tragically and pay tribute to all who gave their lives for their cause.”

Installment 36

The Soka Gakkai delegation offered flowers at the Yuhuatai Revolutionary Martyrs Monument. Two delegation members carrying a wreath of red and pink roses led the others across the stone pavement to the monument’s base. It was engraved with the calligraphy of Mao Zedong: “Long Live the Revolutionary Martyrs.” They laid the wreath there.

The delegation chanted Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, praying for the repose of the martyrs and all who had lost their lives in the Sino-Japanese War. Their voices resonated across the Nanjing landscape and into the clear skies above. Visitors to the memorial park looked on from a distance.

When the chanting ended, Shin’ichi approached the onlookers and greeted them in Chinese with a smile. They cheerfully returned the greeting.

The sight of a group of Japanese visiting Nanjing with palms pressed together in prayer in front of the monument seemed to move them. Shin’ichi and the others extended their hands, and adults and children alike smiled and shook them.

There are no borders when it comes to honoring and praying for the deceased. The spirit of prayer brings people together.

The Jiangsu official guiding the Japanese group introduced them: “This is a delegation from Japan led by President Yamamoto of the Soka Gakkai. President Yamamoto has built a bridge of friendship between our two countries.”

A friendly conversation ensued.

“We offered prayers for the revolutionary martyrs and all who lost their lives in the war,” Shin’ichi said. “We also prayed for the lasting happiness of the people of Nanjing.

“Some of you may have lost family members or relatives in the war. I lost my dear eldest brother. War is barbarous. It is cruel. It must be prevented at all costs. That is why I’m determined to dedicate my life to building peace and friendship between our countries.”

Installment 37

Shin’ichi continued: “I still cannot forget the sight of my grieving mother sobbing, her shoulders shaking, when she learned that my brother had been killed in the war. I understand the pain and sorrow of those of you who have endured a similar experience. That’s why I have resolved to dedicate my life to peace. I have vowed to build an indestructible bridge of friendship linking Japan and China.

“Now, visiting Nanjing and meeting all of you, I have made new friends. The bridge of friendship has expanded even further. Let’s work together to build an everlasting rainbow bridge of peace.”

Those gathered expressed agreement with Shin’ichi’s sentiments as they were translated into Chinese, and some reached out to shake his hand again, their faces etched with emotion.

The delegation next went to visit the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge. Located in the northwest sector of the city, it was a major artery connecting north to south in eastern China. When they arrived, a guide gave them a detailed explanation in front of a 1:300 scale model of the bridge. She was a young woman about 20 years old.

“Construction took almost nine years, from 1960 to 1968,” she began. “The bridge has two levels, the upper level for automobiles and the lower level for trains. The train level is 6,772 meters (22,218 feet) long and the automobile level is 4,589 meters (15,056 feet) long. It is 19.5 meters (64 feet) wide. The Chinese people designed and built the bridge with their own knowhow and technology.”

The Soviet Union had planned to assist with the bridge, but conflict between the two countries caused the Soviets to withdraw their support. In the spirit of self-reliance, however, the Chinese overcame the difficulty and completed the bridge with great success.

Shin’ichi felt hopeful for the future as he listened to the young woman speak with such pride and enthusiasm. Countries and organizations whose young people forge ahead joyfully with confidence and pride are destined to flourish and develop.

Installment 38

On the afternoon of September 16, the Soka Gakkai delegation visited the Meiyuan New Village Memorial Hall. This was the site where Zhou Enlai and his associates had their offices and lodgings during the peace negotiations between the Chinese Nationalist Party and the Chinese Communist Party from May 1946 to March 1947.

In 1937, the Nationalist and Communist parties had formed the Second United Front, an alliance to resist the Japanese. In 1945, Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration and surrendered unconditionally to the Allied Forces; thus China was victorious.