The following text is Ikeda Sensei’s Foreword to The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, the first volume of the Soka Gakkai’s official English translation of Nichiren’s collected works.

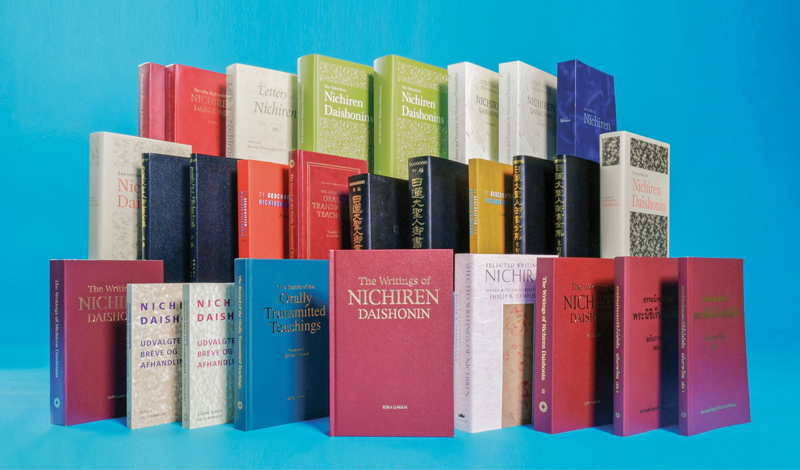

The publication in a single volume of the translations of 172 writings of Nichiren Daishonin, including his five major works, is indeed wonderful news, not only for members of the Soka Gakkai International (SGI), but for all English-speaking people interested in Buddhism. This volume is the translation of works in the Nichiren Daishonin gosho zenshu (The Complete Works of Nichiren Daishonin). Now a good half of the contents of that volume has been translated and published in English.

Looking back, I recall that the Gosho zenshu was published in April 1952, about one year after my mentor, Josei Toda, became the second president of the Soka Gakkai. Since then, the members of the Soka Gakkai in Japan have been fond of reading the Gosho zenshu as they have persevered in spreading the Buddhist teachings widely, exactly as the Daishonin willed, for the peace and prosperity of humankind.

Particularly since my visit to the United States in 1960, my first trip outside Japan, the teachings of Nichiren Daishonin have transcended national boundaries and spread to numerous countries around the world. Now the number of countries I have visited has also grown to fifty-four.

Today the expansion of Nichiren Daishonin’s Buddhism to 128 countries and territories worldwide [192 countries and territories in 2022] attests to the realization of these golden words of the Daishonin: “The moon appears in the west and sheds its light eastward, but the sun rises in the east and casts its rays to the west. The same is true of Buddhism. It spread from west to east in the Former and Middle Days of the Law, but will travel from east to west in the Latter Day” (“On the Buddha’s Prophecy,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 401).

A world religion invariably has its sacred scriptures, or original texts. In Buddhism, for instance, there are sutras that record the teachings of Shakyamuni; in Christianity, there is the Bible; in Islam, the Koran.

The scriptures of Nichiren Daishonin’s Buddhism are called the “Gosho.” (“Go” is an honorific prefix and “sho” means writings; thus, literally, honorable writings.) These writings have a distinguishing feature that sets them apart from the sacred texts of other religions. It is the fact that the founder, Nichiren Daishonin, wrote those works himself. Though the originals of many of those works have been lost, many important writings, including more than half of those known as the ten major works, have been handed down to the present in their original form. Naturally, with the worldwide spread of this Buddhism a demand has grown for the translation of those works, and efforts are now being made in many countries in that direction.

The Daishonin’s successor, Nikko Shonin (1246–1333), envisioned early on that, for the sake of worldwide propagation, the writings of his teacher were certain to be translated in the future. He declared: “Just as when the Buddhism of India spread eastward, the Sanskrit texts were translated and introduced in China and Japan, so when the time comes to widely declare the sacred teachings of this country, the Japanese texts are sure to be translated and spread in China and India. There is no reason to argue over translations that will benefit far-off lands. I alone worry about changes being made according to personal views” (Gosho zenshu).

Buddhism calls our present age the Latter Day of the Law. It is a period described in the sutras as an evil age defiled by the five impurities, in which people’s lives are muddied, and their confusion of thought is extreme. I am convinced that the Gosho is the one book that can dispel the darkness of this period and illuminate the third millennium. I believe it is the Gosho of Nichiren Daishonin that is indeed the scripture for the Latter Day of the Law, the scripture for all eternity.

The Gosho is a work of faith, of philosophy, of daily living, of eternal peace, and of boundless hope. It is set with myriad jewels of guidance. SGI members have read a single passage of the Gosho with their entire life, and not only changed their lives for the better but also achieved their human revolution.

What is the purpose of our studying the Gosho? The answer is expressed clearly in the following passage: “Believe in the Gohonzon, the supreme object of devotion in all of Jambudvipa. Be sure to strengthen your faith, and receive the protection of Shakyamuni, Many Treasures, and the Buddhas of the ten directions. Exert yourself in the two ways of practice and study. Without practice and study, there can be no Buddhism. You must not only persevere yourself; you must also teach others. Both practice and study arise from faith. Teach others to the best of your ability, even if it is only a single sentence or phrase” (“The True Aspect of All Phenomena,” WND-1, 386).

The main elements of the practice of Nichiren Daishonin’s Buddhism are summed up in this passage. What is important is, first, faith; second, practice; and third, study. Strong faith leads us directly to Buddhahood. And it is practice and study that deepen and strengthen that faith. For us, study must never be a mere accumulation of knowledge. It must be strictly a practical study to deepen one’s own faith and elevate one’s own state of life.

Moreover, the path of practice and study leads to the Gohonzon and to society. Because of practice and study, we face the Gohonzon, recite the sutra, and chant daimoku. With the wisdom and life force gained thereby, we carry out our practice and study in the midst of society. Herein lies what we call the bodhisattva way. That is the action of leading other people toward lasting happiness while striving to establish enduring peace for humanity. That practice begins with the inner reformation of the individual, and through that practice, the substance of our lives is deepened and enriched. The ultimate of those changes is the attainment of Buddhahood in this lifetime, or in modern terms, human revolution or self-actualization.

When the Daishonin talks about the Lotus Sutra, it is no longer a mere sacred scripture of the past. How overjoyed those who heard his teachings must have been on learning that the Lotus Sutra is alive in the realities of life, and that it teaches one’s own precious dignity. Our attitude when we read the Gosho should be the same.

The Gosho was written in thirteenth-century Japan. No matter what idea one expresses, one can never avoid what the sociologist Karl Mannheim described as the “existential determination of knowledge.” That is, it is perfectly natural that ideas be bound by various conditions of the society and age that are quite unrelated to the ideas themselves.

Thus, the Daishonin’s writings also reflect the cultural and social conditions of his time. Nevertheless, universal principles both timeless and unchanging are beautifully expressed therein. Our responsibility, I believe, is to read and extract those principles, and bring them to life in the present.

To give just one example, the Daishonin writes, “Even if it seems that, because I was born in the ruler’s domain, I follow him in my actions, I will never follow him in my heart” (p. 579). In modern terms, we might say that this well-known passage from “The Selection of the Time” expresses the ideals of freedom of spirit, freedom of religion, and freedom of thought.

Because of the pioneering nature of the Daishonin’s ideas, he was rejected by the feudalistic society of his time. At the Daishonin’s asserting that a debate on the teachings—in other words, discussion—is the only fair means of determining the superiority of a religion, the eminent priests of various schools, who were in collusion with government authorities, responded with violence unacceptable in a religious person.

In that sense, the Gosho is also the record of the Daishonin’s confrontation with the leaders of the political and religious worlds of his day. And the motivating power for that unyielding struggle was none other than his strength of spirit. The Daishonin writes: “Everyone in Japan, from the sovereign on down to the common people, without exception has tried to do me harm, but I have survived until this day. You should realize that this is because, although I am alone, I have firm faith” (“The Supremacy of the Law,” WND-1, 614).

The Daishonin clearly describes his circumstances during this period in this passage of “Letter from Sado”: “It is the nature of beasts to threaten the weak and fear the strong. Our contemporary scholars of the various schools are just like them. They despise a wise man without power, but fear evil rulers. They are no more than fawning retainers. Only by defeating a powerful enemy can one prove one’s real strength. When an evil ruler in consort with priests of erroneous teachings tries to destroy the correct teaching and do away with a man of wisdom, those with the heart of a lion king are sure to attain Buddhahood. Like Nichiren, for example. I say this not out of arrogance, but because I am deeply committed to the correct teaching. An arrogant person will always be overcome with fear when meeting a strong enemy” (WND-1, 302).

In the midst of that battle with authority and power, in which he never begrudged even his life, the meticulousness of the Daishonin’s concern for his followers is absolutely astonishing. In response to the offerings he received from them, he wrote letters to each one, noting the items they had sent, and encouraging them in their faith. And to those believers grieving for the husband or child they had lost, he extended the utmost sincerity, giving them the courage and hope to live.

Religion exists to resonate vibrantly within each person. Even if one discusses the happiness of all human beings, if it is spoken of apart from the happiness of a single human being, that is mere theory.

The Daishonin writes: “The heart of the Buddha’s lifetime of teachings is the Lotus Sutra, and the heart of the practice of the Lotus Sutra is found in the ‘Never Disparaging’ chapter. What does Bodhisattva Never Disparaging’s profound respect for people signify? The purpose of the appearance in this world of Shakyamuni Buddha, the lord of teachings, lies in his behavior as a human being” (“The Three Kinds of Treasure,” WND-1, 852).

It is when the fruits of studying the Gosho show in our own behavior that we can say we have truly read it.

Thus I am praying that, with great seeking spirit and deep faith, SGI friends throughout the world will tackle the serious study of the Gosho. In conclusion, I would like to express my heartfelt appreciation to the staff of the Gosho Translation Committee, who were in charge of the translation and editing of this volume. I also offer my deep gratitude to Dr. Burton Watson, the translator of The Lotus Sutra, who made so many invaluable contributions in translation.

Daisaku Ikeda

President

Soka Gakkai International

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles